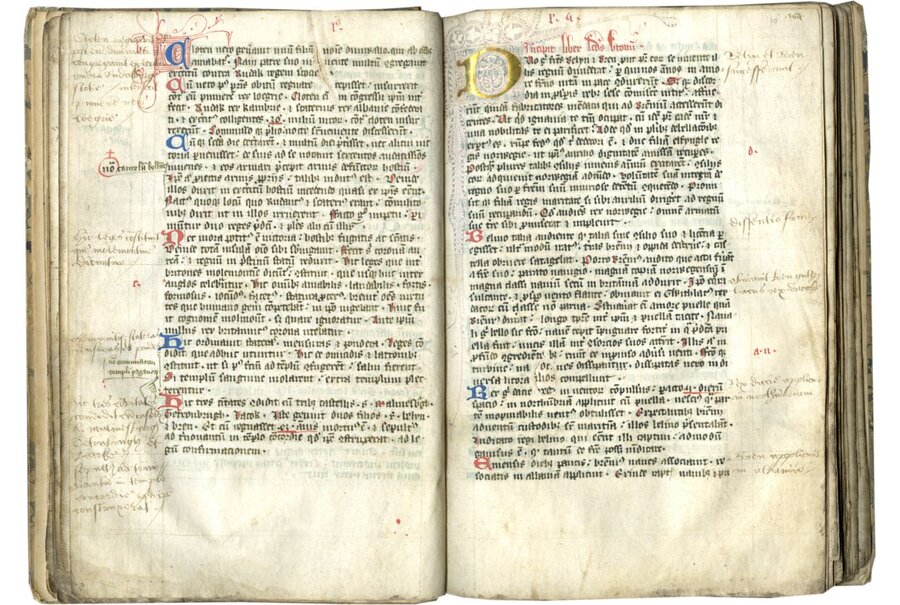

Burnished gold and intricate pen decorations grace a chapter opening in this chronicle of English history, the Eulogium historiarum, TM 836, ff. 9v-10, England (Malmesbury?), c. 1375-1400

Burnished gold and intricate pen decorations grace a chapter opening in this chronicle of English history, the Eulogium historiarum, TM 836, ff. 9v-10, England (Malmesbury?), c. 1375-1400

If you caught our post on faces in the flourishes, you will have seen some of the quirky drawings in our newly posted English chronicle manuscript.

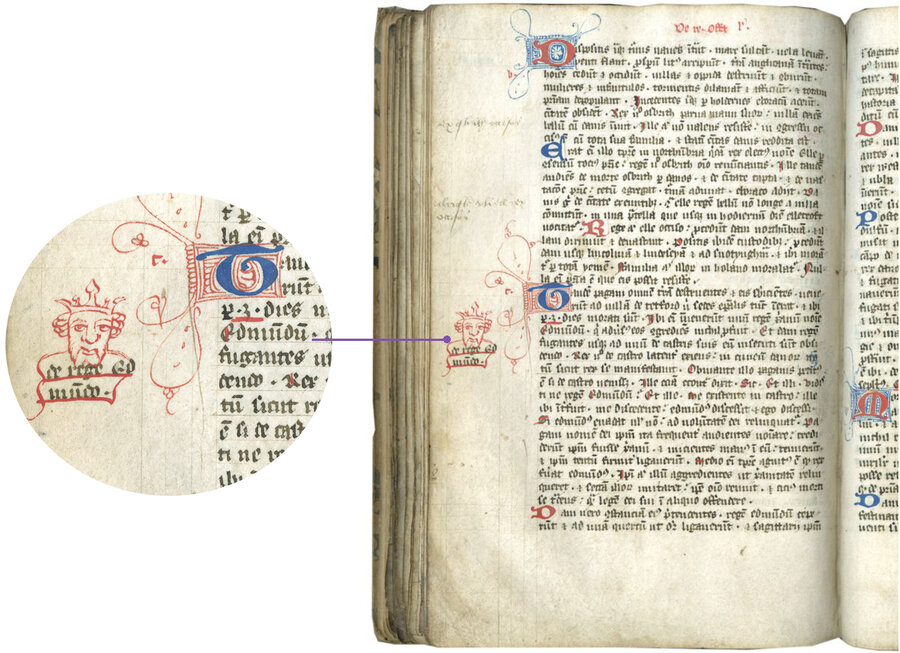

What you won’t have seen there, though, are the three places in that book’s margins where we can put a name to a face. In fact, as you can see here, the scribe has done so himself.

The king who gazes out of the margin here accompanies the caption “de rege Edmundo” (of King Edmund), TM 836, f. 38v

Many kings in this chronicle are identified by marginal notes like this one. And yet, those noted earlier in the margin do not receive such portraits, nor do many that follow. So why King Edmund? Why not Leir or Arthur or any number of other fascinating figures in Britain’s early history?

Edmund’s sole claim to fame is his grisly death. A ninth-century Anglo-Saxon king of East Anglia, he almost certainly died at the hands of a Viking invading force named, rather dramatically, the Great Heathen Army. But medieval writers of histories and saints’ lives tell a more colorful story. This chronicle, for example, relates how this formidable army, having realized Edmund was a Christian and a king, tied him to an oak tree and shot him with arrows until, as the text puts it, his body bristled with as many shafts as a hedgehog has spines. Then, in the interest of being thorough, they chopped off his head. Some stories of his martyrdom continue with accounts of the adventures of the disembodied head, its miraculous speech, and its devoted wolf friend. So perhaps the artist had a penchant for English martyrs?

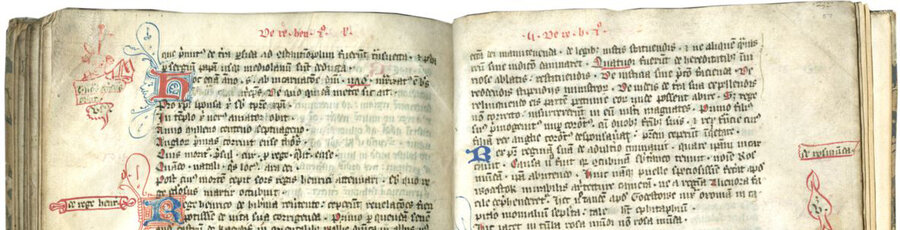

Thomas à Becket's grisly end, TM 836, f. 56v (detail)

In that case, the next marginal portrait certainly fits. Thomas à Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury in the twelfth century, is one of England’s best-known saints (his is the shrine the pilgrims wish to visit in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales), and the drawing of him here emphasizes the manner of his martyrdom. Look closely at the faded image and you can see that the top of his head has been almost entirely hacked off. A sword protrudes from his head where the skull cap has been removed. Though shocking to us, such depictions of Thomas were not at all uncommon in the Middle Ages and they follow contemporary accounts of Thomas’s death by the swords of four knights, acting in the interests of King Henry II – and possibly even at his implicit command.

Both the drawing and the text to its right show signs of erasure, TM 836, ff. 56v-57 (detail)

Both the drawing and the text to its right show signs of erasure, TM 836, ff. 56v-57 (detail)

Wondering why this drawing is so difficult to make out now? It was probably erased by an early reader in an act of censorship, along with Thomas’s name. Since Becket was celebrated as a man of the Church who stood up to royal power, his cult was a particular target of Henry VIII after his break with Rome. Henry, for obvious reasons, wished to discourage such resistance, and in 1538 he and Thomas Cromwell issued a Royal Proclamation denouncing Becket as a traitor and calling for the removal of his name and image from churches and books.

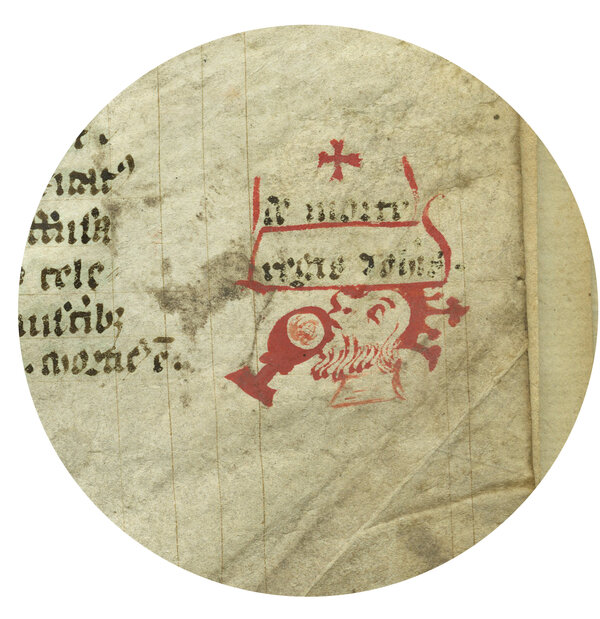

King John poised to drink his poison, TM 836, f. 62 (detail)

King John poised to drink his poison, TM 836, f. 62 (detail)

This final figure was no saint. Best known, perhaps, as the English king whose rebellious barons compelled him to agree to the Magna Carta in 1215, King John had a similarly troubled relationship with the Church – he was even briefly excommunicated following a dispute over his rights to make ecclesiastical appointments. He was also reviled by medieval chroniclers – writing after his death, the thirteenth-century monk and historian Matthew Paris went so far as to write, “Foul as it is, hell itself is defiled by the fouler presence of John” – and he was damned as an incompetent ruler, cruel tyrant, sexual predator, and murderer.

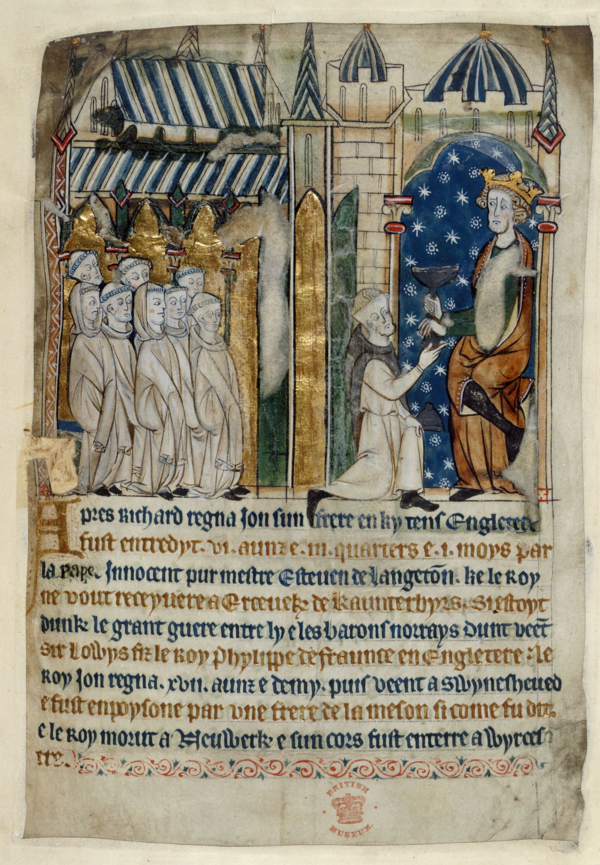

A monk presents King John with a poisoned drink as his brothers look on in this book of English chronicles and cartularies, London, British Library, Cotton MS Vitellius A.xii, f. 5v

A monk presents King John with a poisoned drink as his brothers look on in this book of English chronicles and cartularies, London, British Library, Cotton MS Vitellius A.xii, f. 5v

In light of this unconcealed loathing, it is not surprising that many medieval histories attributed his death not to dysentery (the likely culprit) but to poisoning at the hands of a heroic monk. That is the view adopted in this chronicle. During John’s visit to Swineshead Abbey, a monk presents him with a chalice of poison and the traditional Saxon salute, “Wassayl.” John speaks the customary response, “Drinkhayl,” and, once the monk has drunk from the chalice, drinks freely from it himself. Both then die in horrible agony, though, as the text notes, the community mourns the monk and honors his sacrifice – King John? not so much.

This third marginal drawing follows the first two, then, in celebrating an English martyrdom. In fact, the chronicle explicitly identifies the monk’s act in this way. Here, though, we may speculate that at least one among the book’s monastic audience derived some satisfaction from the immediate fall-out of his fellow monk’s death, that in dying, he brought down a king as well.