In case you haven’t noticed, we updated the Text Manuscripts site last month; you can find the new inventory here. Do take a look!

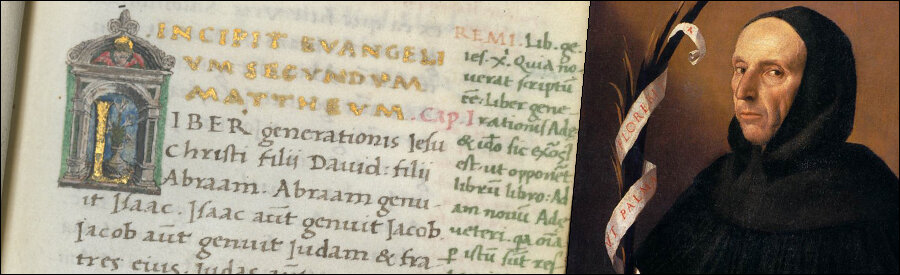

This post, about Gospel Books, was prompted by one of my favorites from the update, a manuscript of the four Gospels made in Italy in the fifteenth century.

Les Enluminures, TM 1323, Gospels, Italy (Florence?), c. 1475-1500, f. 193, Beginning of the Gospel of John

Some of the most famous medieval manuscripts are Gospel Books (that is, manuscripts with the complete text of the four Gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, accompanied by introductory texts including prologues, and, often, the Eusebian Canon Tables). Chances are that even someone who never thinks about the Middle Ages will have heard of two of the great monuments of Insular art, the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Book of Kells: the Lindisfarne Gospels (which has been called the “most spectacular manuscript to survive from Anglo-Saxon England”) was made c. 700 on Holy Island, or Lindisfarne, off the northeast coast of England;

The Lindisfarne Gospels, British Library, Cotton MS Nero D IV, The Beginning of the Gospel of John

the Book of Kells dates from c. 800 and was most likely made in Iona, Scotland

The Book of Kells (Trinity College Dublin MS 58), f. 7v, The Virgin and Child

The Gospels of Henry the Lion is almost equally famous (although for a different reason). Created at Helmarshausen Abbey for Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony (c.1129-1195) c.1180, it was sold at auction on December 6, 1983 at Sotheby’s in London for more than $11.7 million, more than ten times the then highest pricepaid for any work of art, an astonishing statistic!

Gospels of Henry the Lion, Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2, f. 172, Christ in Majesty

At Les Enluminures, one of our most prized manuscripts was the Liesborn Gospels, copied in Northwestern Germany c. 980-1000, for a community of woman under the patronage of Berthildis It was very likely copied at Liesborn Abbey, and remained there until 1803, when the foundation was secularized. After a period of wandering (including a stay in the United States in the Doheny Collection), it returned to Liesborn, now a museum, in 2019.

Museum Abtei Liesborn, The Liesborn Gospels, Beginning of Luke

These Gospel Books (and the many, many hundreds of others that survive–many, of course, much less lavish than the ones highlighted here) were liturgical manuscripts, made to be read during the Mass. Gospel Books can be found from the very earliest centuries of the Middle Ages (the Codex Vercellensis dates from the fourth century), right through to the end of the period (here is an example copied in Spain in 1543, formerly TM 385). But the vast majority of surviving Gospel Books date from the twelfth century or earlier. The Gospels of Henry the Lion are in fact a rather late example. In the High and later Middle Ages Evangeliaries, which contains the readings for the Mass arranged in liturgical, rather than biblical order, and Missals, the liturgical manuscript that includes all the texts needed to say the Mass, including the readings, were much more common than Gospel Books. (For anyone interested in reading more about the origin and history of the Missal, I highly recommend this article: A. J. M. Irvine, “On the Counting of Mass Books,” Archiv für Liturgiewissenschaft 57 (2015), pp. 24-48.)

The decline in the production of new Gospel Books after the twelfth century, however, does not necessarily mean that Gospel Books were no longer used in churches across Europe. Indeed, it seems likely that Gospel Books from the earlier Middle Ages, which were treasured as sacred objects, continued to be actively used for many, many centuries. To cite a modern example, the Gospel Book of St. Augustine (also called the Canterbury Gospels) from the sixth century is still carried in procession at the enthronement of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

St. Augustine Gospels, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 286, f. 129v, St. Luke.

On the right: Archbishop Justin Welby kissing the Gospels of St. Augustine (BBC news, 2013)

Gospel Books used for readings during the Mass were, in general, moderately large volumes. The Lindisfarne Gospels includes 259 folios and measure 365 x 275 mm.; the Book of Kells, 340 folios, 330 x 255 mm.; Henry the Lion’s Gospels, 226 folios, 342 x 255 mm.; and the Liesborn Gospels, 169 folios, 304 x 242 mm. (Note that I am making no claims that the size of this small group of illustrious examples is representative of the size of medieval Gospel Books overall, but many surviving examples do fall within this range of sizes).

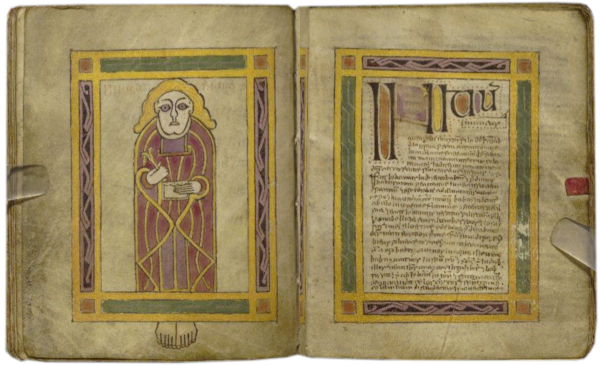

But not all Gospel Books were large. A notable exception is the small group of manuscripts known as Irish Pocket Gospel Books. The essential article on these manuscripts by Patrick McGurk discusses eight examples, all from Ireland, dating from the seventh through the ninth centuries (Patrick McGurk, “The Irish Pocket Gospel Book,” Sacris Erudiri 8 (1956), pp. 249-270). The largest, the Book of Dimma (Dublin, Trinity College, MS 59, from the eighth century, has 74 folios and measures 175 x 142 mm. The smallest, known as the Cadmug Gospels (Fulda, LB, Codex Bonifatianus 3), also from the eighth century, measures only 125 x 112 mm. with 65 folios. McGurk suggested that many of these manuscripts were personal copies of the Gospels that were carried in satchels by travelling Irish monks. At least one, however, includes evidence of liturgical use, and the question of how they were used is difficult to answer now with any certainty.

The Cadmug Gospels, (Fulda, LB, Codex Bonifatianus 3), ff. 19v-20, beginning of the Gospel of Mark

It is certainly true that Gospel Books were used for more than the readings of the Mass. The Gospel of St. Cuthbert (or the Stonyhurst Gospel), includes only the Gospel of St. John, setting it apart from “Gospel Books” per se. It includes 90 folios and measures 137 x 95 mm. Copied in the early eighth century at the monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow (the same monastery that produced the Codex Amiatinus), it survives in its original binding–the earliest European book to do so. Sources from the twelfth century say that it was found buried with St. Cuthbert, and this book has a long association with this saint and his miracles; it has almost become a relic. A tiny fifth- or sixth-century copy of St. John’s Gospel from Chartres, Paris, BnF MS 10439, measuring only 75 x 60 mm. with 263 folios, has been grouped with Gospel Books that were treasured as amulets. It is interesting, however, that this tiny manuscript is copied in a beautiful and very legible uncial script (reminding us that amulet or not, it is also a book, and a readable one at that), as is the St. Cuthbert Gospel. (Their script contrasts sharply with the script found in Irish Pocket Gospels, which are copied in a very small, highly abbreviated Irish pointed minuscule.) Gospel Books were used for oath-swearing and were also used to preserve copies of non-biblical texts including legal documents, included among their pages for safe keeping. Everyone interested in these aspects of Gospel Books–as relics, as oath-books, and as repositories of texts–and the physical evidence discernible in surviving manuscripts linked to these functions, should seek out Kate Rudy’s new book, Touching Parchment: How Medieval Users Rubbed, Handled, and Kissed Their Manuscripts. Volume 1: Officials and Their Books, Open Book Publishers, 2023, especially pp. 51-79, for a characteristically lively and insightful discussion of the topic.

The St. Cuthbert Gospel, British Library, Additional MS 89000, f. 1, beginning of Gospel of John.

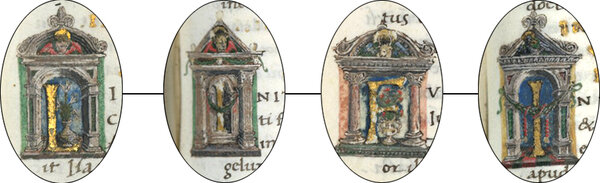

With all this background in mind, let’s take a closer look at the manuscript that prompted this blog. This much later manuscript was copied in Italy in the fifteenth century; it includes the complete text of the four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), with the traditional prologues, but without Canon Tables. It is quite remarkably small, with 258 folios, measuring only 113 x 77 mm.– making it smaller in fact than any of the extant Irish Pocket Gospel Books from so much earlier in the Middle Ages. It is a very refined manuscript, copied on beautiful parchment in a skilled humanistic script. Each Gospel begins with a gold initial enclosed in a classical archway or portico with the tiny symbol of the Evangelist in the tympanum (Matthew’s angel, Mark’s lion, Luke’s ox, and John’s eagle).

Les Enluminures, TM 1323, Gospels, Italy (Florence?), c. 1475-1500, initials at the beginning of Matthew, f. 10, Mark, f. 78, Luke, f. 121v, and John, f. 193.

The symbols of the Evangelists were used in manuscripts of the Gospels since the early Middle Ages. But the style of these exquisite little initials that combine a classical motif with references to the Gospels is very unusual; we know of no parallel.

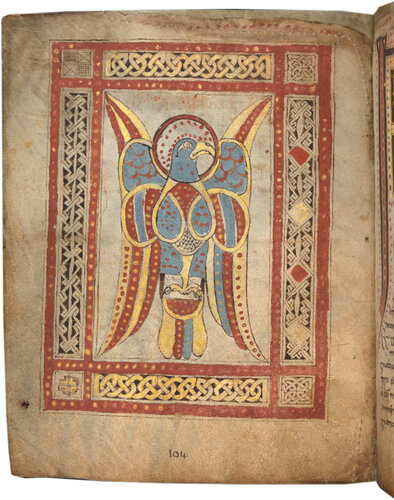

Book of Dimma, late eighth century, Trinity College Dublin, MS 59, f. 104v, John’s Evangelist Symbol

To this point, our discussion has emphasized the sacred functions of the Gospel Book in the Middle Ages. But our tiny humanist manuscript points to another type of Gospel manuscript, namely manuscripts copied for study, like manuscripts of the Gospels accompanied by the Glossa ordinaria, or Ordinary Gloss, which presented the sacred text accompanied by commentaries together on the same page.

Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery, MS W.15, Glossed Gospels, England, late twelfth or early thirteenth century, f. 5, The beginning of Matthew with commentary.

Our manuscript also includes a commentary, or a gloss, on its first twenty-six folios (through Matthew chapter 9). Copied in a truly tiny script in the margins around the biblical text (and in one case, f. 9v, occupying a complete page facing the beginning of Matthew), often using red ink, are selected passages from various sources, primarily patristic authors, with some later writers, and occasionally, the Glossa ordinaria. The source for the commentary in our manuscript was almost certainly the Catena aurea in Matthaeum (The Golden Chain on Matthew) by St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274). Our manuscript includes a small number of carefully selected passages from Thomas’ longer commentary, and is likely a unique, customized version created for the original owner of our manuscript.

Les Enluminures, TM 1323, Gospels, Italy (Florence?), c. 1475-1500, 10v-11, Matthew with marginal commentary

The marginal commentary, even if it doesn’t continue through the whole manuscript, sets our tiny book apart, and suggests it was copied for study. Small and precious, it seems very likely that it was also intended for personal devotion.

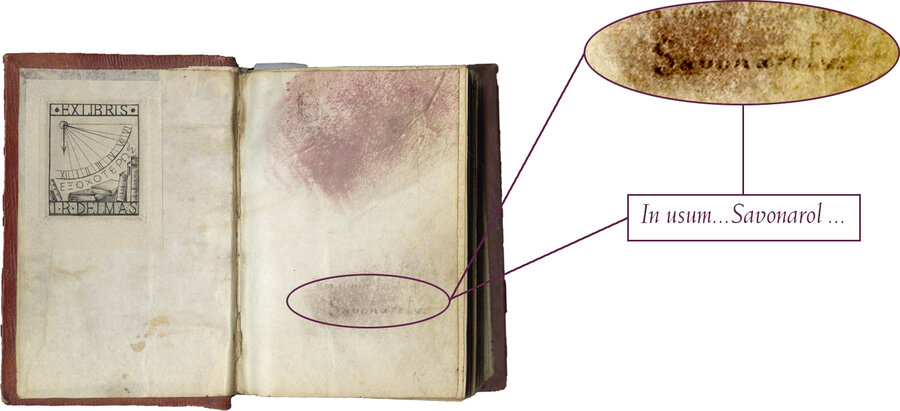

Our manuscript has one final, tantalizing, link with earlier Gospel Books. An added note on the front flyleaf of this manuscript suggests an association with Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498), the famous Florentine preacher and reformer who was executed in 1498.

Les Enluminures, TM 1323, detail of a note on the front flyleaf that can be read, “In usum...Savonarol ...”

Savonarola has never been recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church, but he was venerated by some after his death. As we have seen, the association between Gospel Books and holy men is one with a long tradition in the Middle Ages.

Girolamo Savonarola statue, Ferrara, Italy

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!