Of all the monastic orders founded during the Middle Age, none are as romantic as the Carthusians. The extreme austerity of their way of life has always inspired awe. And their complete withdrawal from the world paradoxically has ensured our perennial fascination. (Forbidden fruit and all that; don’t we always want what we can’t have?) Their most important and ancient foundation, La Grande Chartreuse, in the French Alps near Grenoble is now completely closed to visitors; even traffic is forbidden on the surrounding roads.

In earlier centuries, the monastery had many visitors; the poet, Matthew Arnold (1822-1883), commemorated his own visit in “Stanzas from the Grande Chartreuse”:

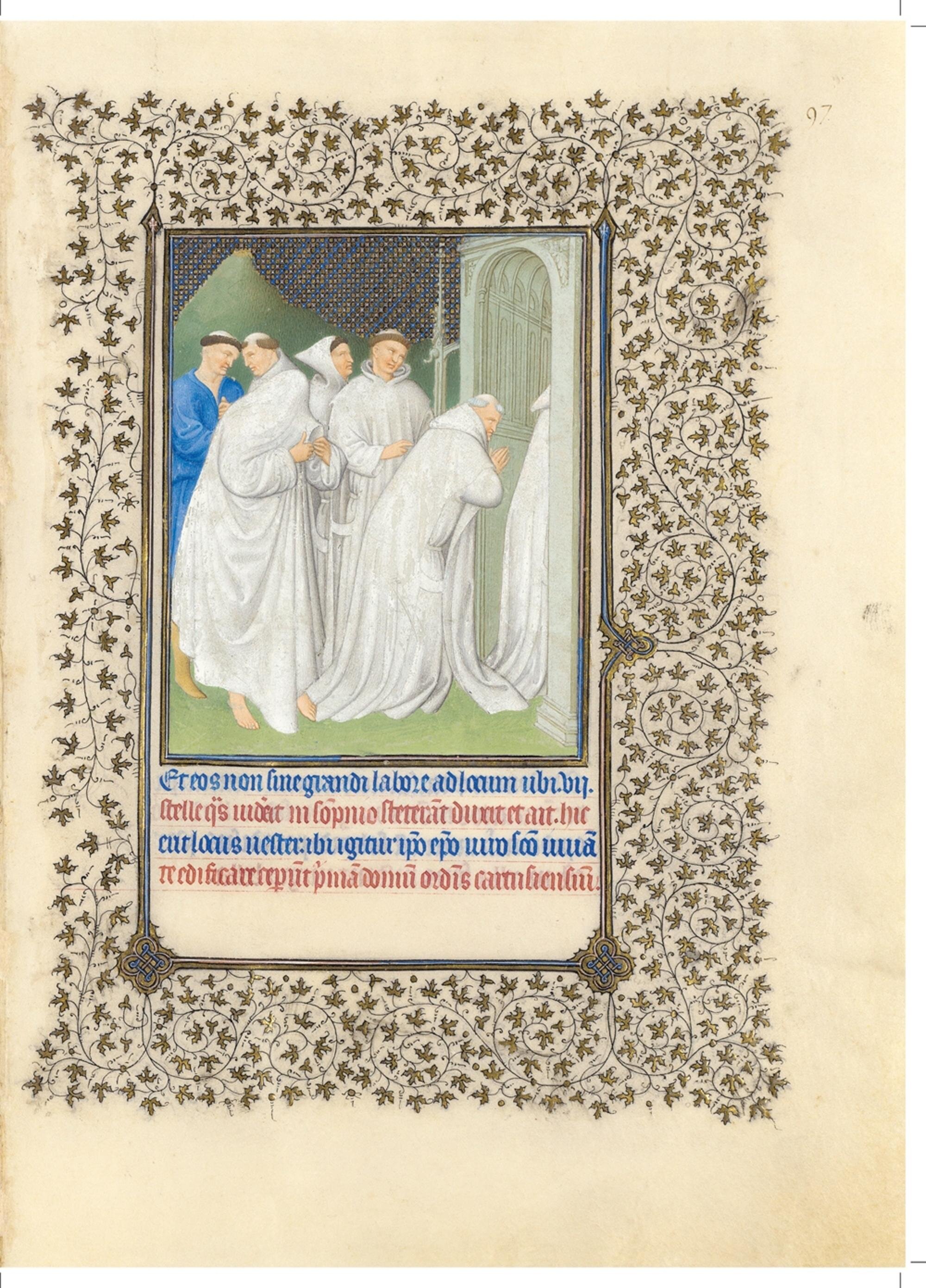

The silent courts, where night and day

Into their stone-carved basins cold

The splashing icy fountains play—

The humid corridors behold!

Where, ghostlike in the deepening night,

Cowl'd forms brush by in gleaming white.

[From Matthew Arnold, “Stanzas from the Grande Chartreuse.”]

St. Bruno and companions entering the Grande Chartreuse; Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, 1405–1408/9 by Paul Herman and Jean de Limbourg, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1), f. 97.

The Carthusian Order was founded by St. Bruno of Cologne around 1084. Inspired by the solitary lives of the early desert hermits, Bruno and six followers built a hermitage in the remote mountains near Grenoble. The way of life that developed from these beginnings was a unique combination of two different visions of the monastic life. Carthusians spend most of their days living as solitary hermits in their own cells, but they are also part of a monastic community. The success of the Carthusians at creating and maintaining this balanced life allows the Order to make the famous claim, “numquam reformata, quia numquam deformata” (never reformed because never deformed).

This was not an easy feat, especially given the austerity of their life. One of the earliest descriptions of their way of life is found in Guibert of Nogent’s (1055-1124) famous autobiographical memoirs:

The church stands upon a ridge . . . thirteen monks dwell there, who have a sufficiently convenient cloister, in accordance with the cenobitic custom, but do not live together claustraliter like other monks. Each has his own cell round the cloister, and in these they work, sleep, and eat. On Sundays they receive the necessary bread and vegetables (for the week) which is their only kind of food and is cooked by each one in his own cell; water for drinking and for other purposes is supplied by a conduit …. There are no gold or silver ornaments in their church, except a silver chalice. They do not go to the church as we do [Guibert was a Benedictine], but only for certain of them. They hear Mass, unless I am mistaken, on Sundays and solemnities. They hardly ever speak, and, if they want anything, ask for it by a sign. If they ever drink wine, it is so watered down as to be scarcely better than plain water. They wear a hair shirt next the skin, and their other garments are thin and scanty. They live under a prior, and the Bishop of Grenoble acts as their abbot and provisor …. Lower down the mountain there is a building containing over twenty most faithful lay brothers [laicos], who work for them …. Although they observe the utmost poverty, they are getting together a very rich library.

[As a side note, just in case some of our readers aren’t familiar with it, Guibert’s autobiography is simply amazing – highly recommended reading – and there are modern translations by Paul J. Archambault, and John Benton; here we are quoting his text from the translation of this passage in D. R. Webster, “The Carthusian Order,” The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York, 1908).]

Carthusians may be holy hermits, but they also proved to be very good at the practical details of governing a monastic Order. The Carthusian Order was a highly centralized one with written customs and statutes, governed by the Prior of their motherhouse, La Grande Chartreuse, and by their General Chapter representing all the charterhouses. Key to their success was a system of visitations, where visitors, appointed by the General Chapter, visited each charterhouse every two years to discover and correct any transgressions against the rules of the Order or other problems.

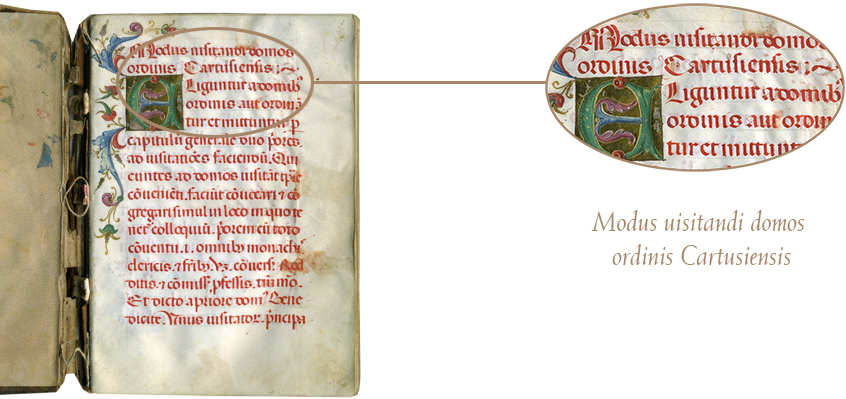

Les Enluminures, TM 333, Northern Italy (Venice?), c. 1500-1525, with later additions c. 1534, f. 1.

The importance of visitations to the Order is reflected in this carefully written and illuminated manuscript, copied for a Carthusian monastery in Northeastern Italy in the early sixteenth century. The manuscript begins with the text of the statutes regulating visitations in Latin, with selected passages repeated in Italian translation, since the lay brothers in the monastery likely did not know Latin. Visitations were formal occasions, accompanied by sermons and prayers, and this manuscript includes several sermons.

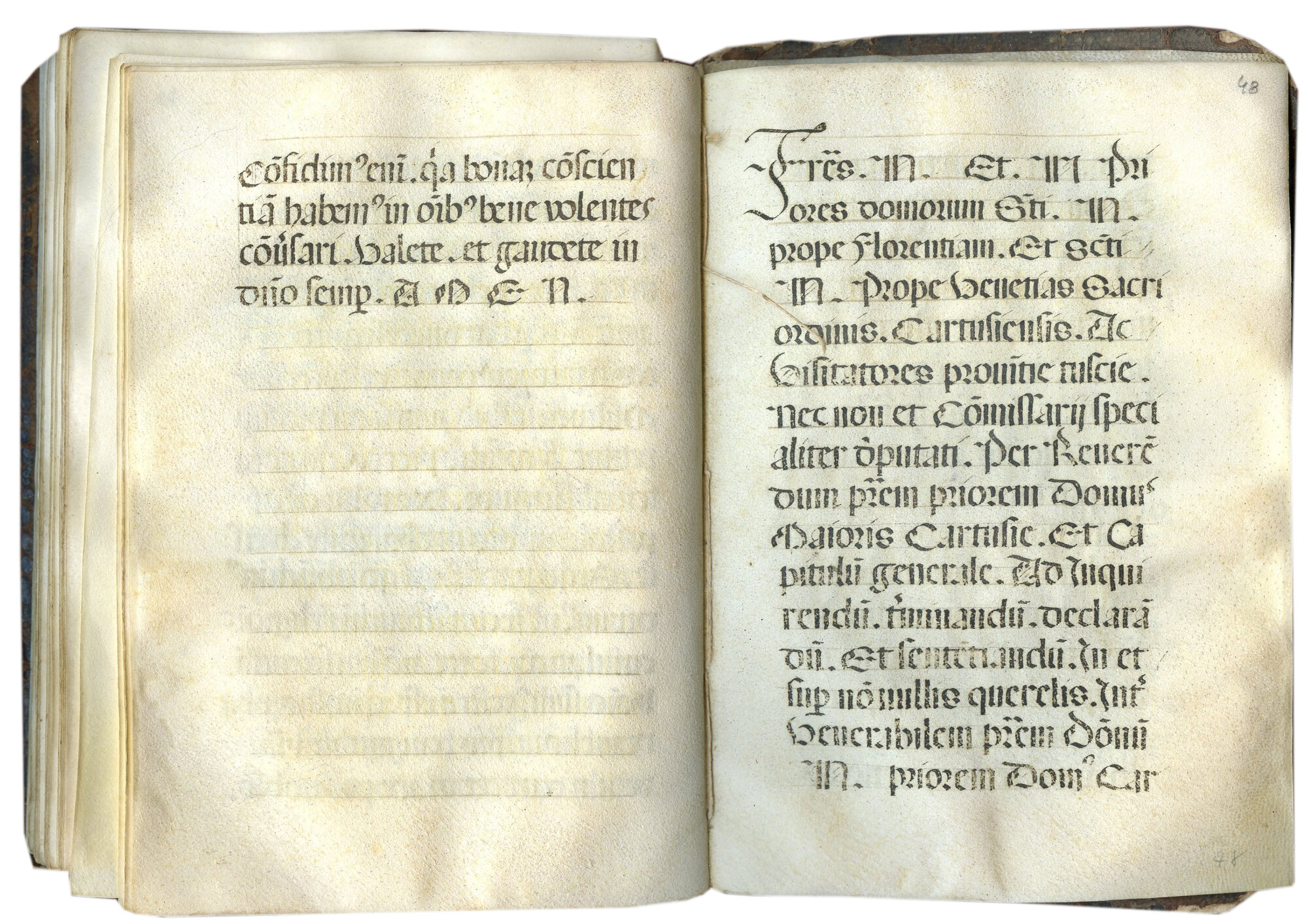

Les Enluminures, TM 333, f. 48, Record of a visitation in 1534.

It concludes with the results of a visitation by the priors of the Carthusian charterhouses near Florence and Venice, settling a dispute between the Prior of the charterhouse of St. John the Evangelist at Calci near Pisa and one of his monks, dated June 22, 1534. The names are not included, but are represented by the letter “N.”

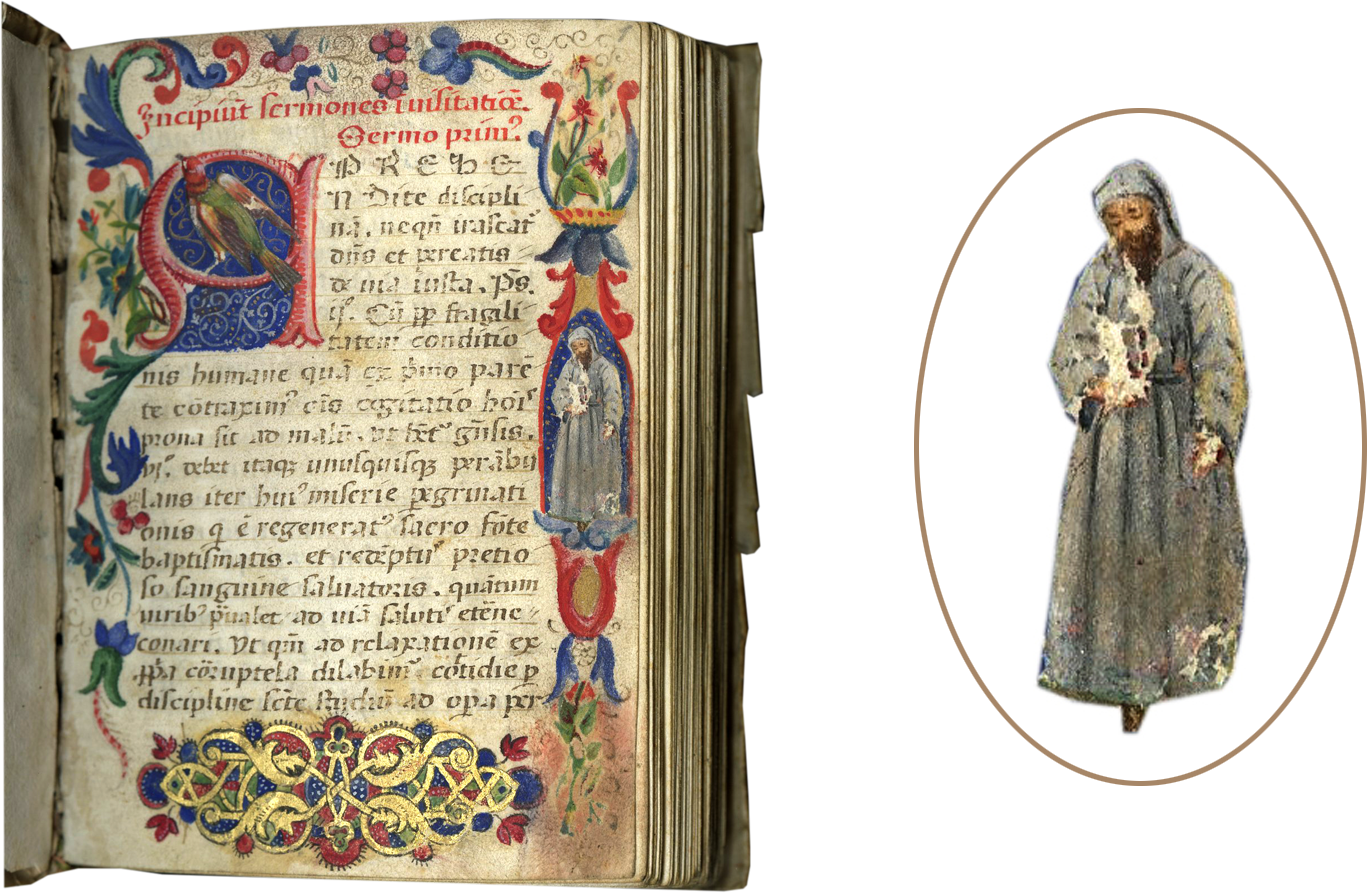

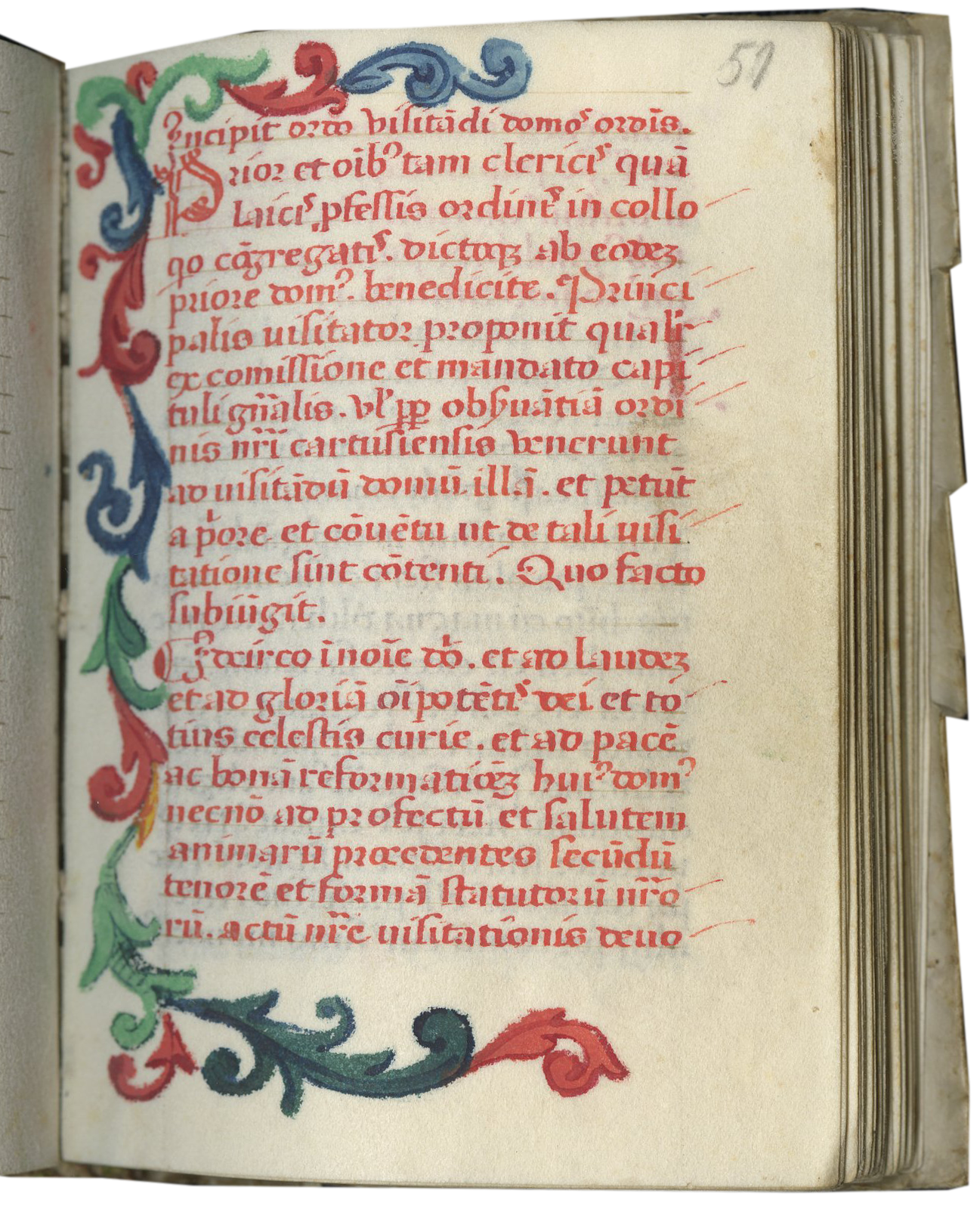

Les Enluminures, TM 1072, Carthusian Rules and Sermons for Visitations, Northeastern Italy, c. 1564, f. 1.

A second Carthusian manuscript from a yet unidentified charterhouse in Northeastern Italy begins with a lavish illuminated border featuring a monk (presumably a Carthusian monk, although the Carthusian white habit looks rather gray here). The text opens with a series of seven sermons to preach at visitations and other occasions (there is one for the election of the prior). These are specifically Carthusian sermons which mention their audience (often “venerable fathers and brothers,” that is the priors and monks present) and sometimes specific Carthusian statutes, on themes that are suitable for a penitential occasion like a visitation.

Les Enluminures, TM 1072, Carthusian Rules and Sermons for Visitations, Northeastern Italy, c. 1564, f. 51.

The actual “ordo” for the visitation follows, describing the procedures (copying out the relevant passages of the statutes) to be followed, and including the text of the prayers and readings. Once again, although the manuscript is mostly in Latin, selected texts are in Italian. Next are lists of general transgressions that the visitators inquire about, followed by more detailed lists organized by office, from the prior down through simple monks. These lists make interesting reading. The sacristan, for example, is asked if he carefully preserves the books in his care.

The manuscript concludes with a generic form to be used for visitations (the specific names are represented by ‘N’), followed by the results of an actual visitation on November 3, 1564, from which we discover that the monastery had ten monks (including the prior), four “conversi” or lay brothers, and two servants, some livestock, and modest stores of food. The visitors then leave instructions concerning correct observance of the Office and Mass and stipulate punishments for various infractions (including a number involving the company of women, which was strictly forbidden).

Brother Hugo and the Bear by Katy Beebe.

Let’s conclude with everyone’s favorite story about the Carthusians. In the twelfth century, Peter the Venerable (c. 1092-1156), abbot of Cluny, was an admirer of the Carthusian way of life, and a close friend of Guigo, the prior of the Grand Chartreuse (d. 1136). His letters include fascinating details of how manuscripts were shared between the two Orders, including one remarkable letter where Peter asks Guigo: “Send us, if you please, the larger volume of St Augustine's letters, for a large part of ours has been accidentally eaten by a bear.”

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!