Autumn, what does it mean to you? Crisper days and chilly nights, a new palette in the garden, asters, pumpkins? A new academic year? For us at Les Enluminures, it means that it is time for the annual Fall update of the Text Manuscripts Site. If you are eager to jump right in, click here to see the manuscripts on the TM site.

We have been as busy as these monks, getting ready for the Text Manuscripts Update; “Monks at Work,” from History of the Church, 1880.

I thought readers of our blog might be interested in a quick look behind the scenes. We customarily add new inventory twice a year, in the Fall, and again in the Winter or Spring (this second update moves around a bit but is scheduled some time between January and April). The Fall update is usually the larger of the two and includes around 30-35 manuscripts. This year’s list included 36 items, of which 29 are still available as I write this.

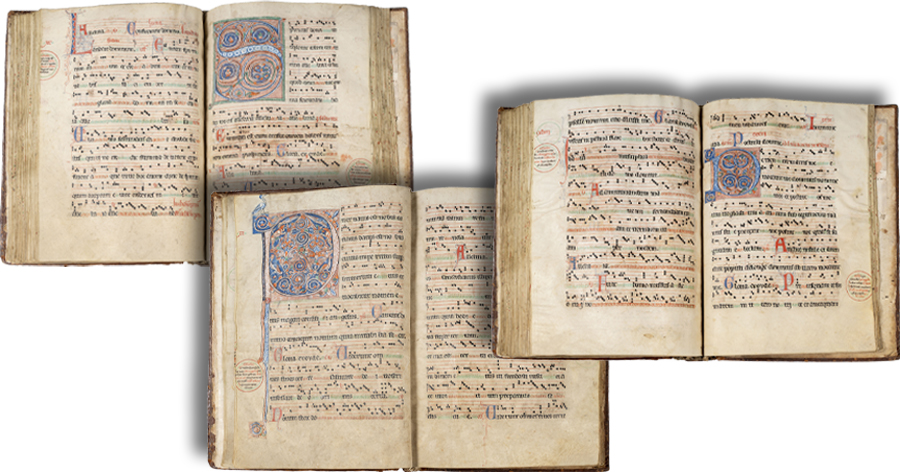

TM 1190, The Barbeau Gradual (Cistercian Use), Northern France, c. 1240-1260 (c. 1255?), ff. 11v-12 (detail).

Getting ready for the update is, to put it simply, a lot of work. Each manuscript is first meticulously described according to the accepted standards of academic descriptions by experts in the field. We describe some of the manuscripts ourselves (in this update, I described some, as did our text manuscripts specialist, Katja Monier), but we also depend on other scholars (for this update, I would like to thank Jenneka Janzen, Stephanie Lahey, Hope Mayo, Stephen Mossman, Elie Dannaoui, and Paul Vinhage for their descriptions). And descriptions are only the beginning. Preparing images and videos and then finally putting everything online is a big project; Fabio Epifani, our director of digital content, manages all that, with help from many others on our team.

One question I am often asked is how long does it take to prepare a detailed description of a medieval manuscript? And my usual reply - it varies a lot - isn’t very satisfying. One published answer comes from Germany, where describing medieval manuscripts has been a national priority since the 1990s, resulting in a series of superb catalogues of the medieval holdings of numerous libraries. Dr. Christoph Mackert of the University of Leipzig has stated: “On the average, ten working days are required to describe a single manuscript; which means, that even more are needed for complex manuscripts, but there are also simple manuscripts that take only a few days.”

Handschriftenportal, the central information platform for medieval and early modern manuscripts in German Collections (still a work in progress).

Does ten days seem like a very long time? maybe not if you’ve read some of the very detailed descriptions in these modern German catalogues. And I should quickly add that we don’t spend ten days on every manuscript described on our text manuscripts site. But there are certainly some complicated manuscripts that have taken that long, as well as many that were described much more quickly. In addition to the complexity of the manuscript being described, the experience of the cataloguer makes a difference as well. I’ve been doing this for many decades, and I work more quickly now than I did at the beginning of my career. Regardless of how long it takes to describe a manuscript, it is satisfying work; every manuscript is different; every description is a new piece of research; and (almost always) it is fun.

From left to right: TM 1190, The Barbeau Gradual; TM 1104, Privilege-book of the Young Handbow of Antwerp (Guild of St. Sebastian); TM 1226, The Rugby-De Brailes Bible; TM 1193, Sermons attributed to MAURICE DE SULLY (perhaps by WILLIAM DE BLOIS?).

Now that you know a bit about our process, I hope you will look at the new additions to textmanuscripts.com. It is a good group, full of interesting things – and some surprises. Many of the readers of this blog will know that our site specializes in Western medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, up to c. 1600. But this cut-off date isn’t carved in stone. If we find something later that we love, we will offer that. And we do love the later manuscripts in this update.

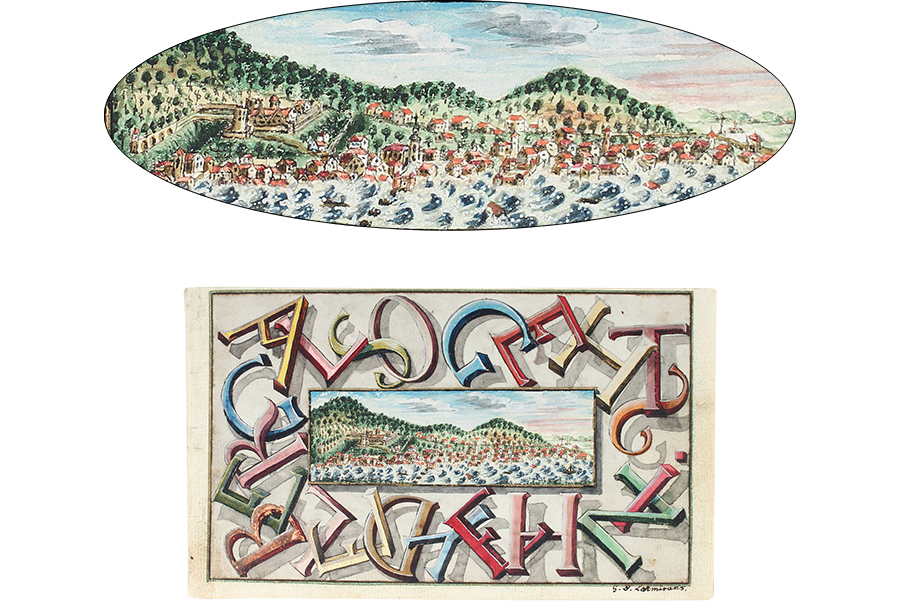

TM 1123, Album Amicorum of Johann Heinrich Hahn from Heidelberg, Western Germany (Heidelberg, Landau, Mannheim, Strasbourg [modern France], Frankfurt), 1784-1792, f. 3.

For example, this Album amicorum that includes a watercolor of one of the greatest natural disasters of the Early Modern period in Central Europe, the Heidelberg flood of 1784. Its distinctive frame of letters, which are represented in three dimensions as if dropped in space in an “alphabet soup,” spell out “Also gehts in Heydelberg.”

TM 1123, Album Amicorum of Johann Heinrich Hahn from Heidelberg, Western Germany (Heidelberg, Landau, Mannheim, Strasbourg [modern France], Frankfurt), 1784-1792, f. 15v.

For those unfamiliar with this genre, album amicorum literally means “album of friends.” These volumes were very popular in Germany from the sixteenth through the nineteenth century. University students, young aristocrats, and others collected entries (which varied, and included sayings, proverbs, poems, wishes, drawings, and more) from their friends and relatives as they travelled. Just like a modern social media account, these albums were proof that their owners had a wide and varied circle of friends.

TM 1127, Boxed set of drawings medieval and post-medieval art, France (Paris), c. 1875-1910(?).

More medieval in content, although dating even later (from the end of the nineteenth or early twentieth century) is this remarkable collection of hundreds of drawings by a yet unidentified, but accomplished, artist, mostly of details from medieval manuscripts. This rich archive, perhaps a preparatory set of designs for one of the many publications on medieval art in this period, is just calling out for further study.

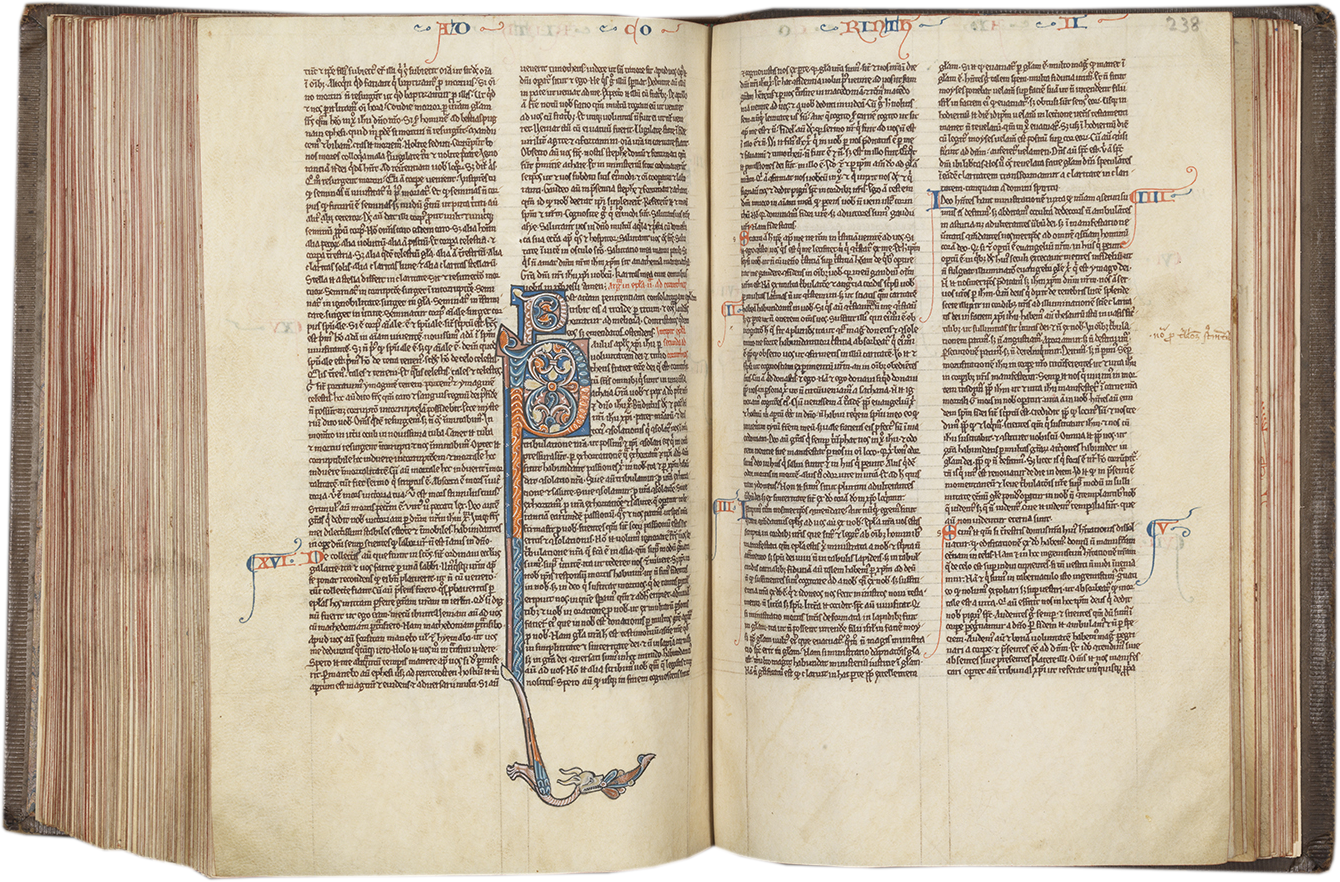

TM 1226, The Rugby-De Brailes Bible, England (Oxford), c. 1230-1250 (perhaps 1230s), ff. 237v-238.

The earliest manuscripts in this update date from the thirteenth century, including this wonderful thirteenth-century Bible from Oxford, newly attributed to the workshop of William De Brailes.

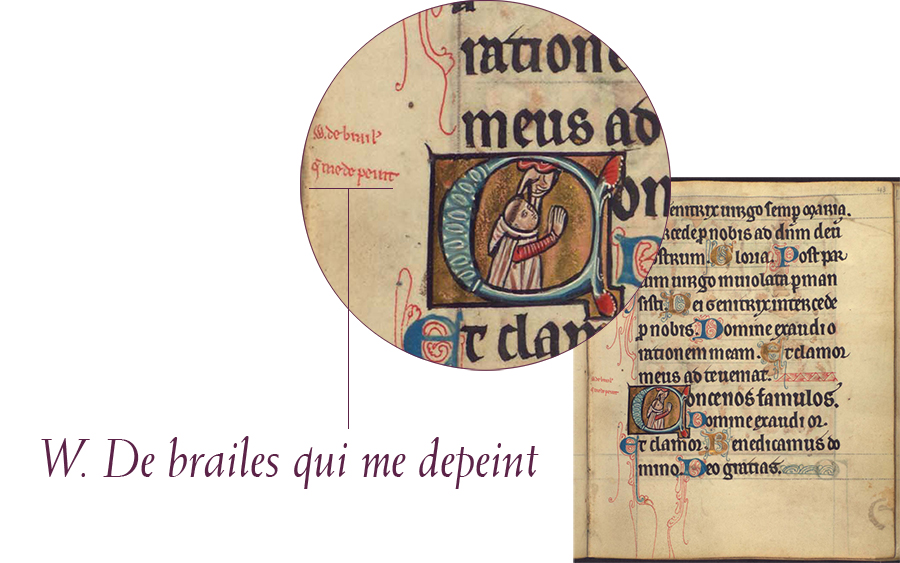

The artist, William De Brailes, British Library, Additional MS 49999, f. 43, Oxford, c. 1240.

William De Brailes is one of only two thirteenth-century English artists know by name. In a Book of Hours now in the British Library (one of the earliest known Book of Hours) he is identified with the phrase, “W. De brailes qui me depeint” (W[illiam] De Brailes who painted me), alongside two initials depicting a tonsured man, kneeling in prayer, almost certainly self-portraits of the artist.

TM 1190, The Barbeau Gradual (Cistercian Use), Northern France, c. 1240-1260 (c. 1255?), ff. 11v-12, ff.88v-89, ff. 145v-146.

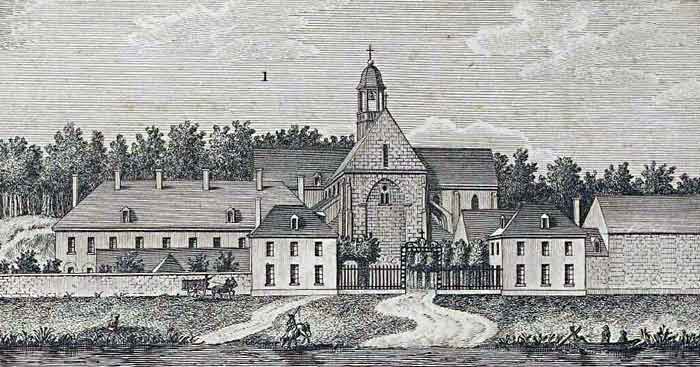

And this large Gradual from the Abbey of Barbeau. The Cistercian Abbey of Our Lady of Barbeau was founded in 1147 in Seine-Port (Île-de-France). In 1156, with the sponsorship of King Louis VII of France (r. 1137-1180), the Abbey was moved to Fontaine-le-Port (Seine-et-Marne) in the archdiocese of Sens. Louis VII would subsequently be buried at Barbeau. Our manuscript was likely completed just in time to be used in their new church.

The abbey of Barbeau, immediately before its demolition in 1837

A Gradual is the liturgical manuscript containing the sung portions of the Mass. Our manuscript is quite large, measuring 390 x 270 mm. or 15.3 x 10.6 inches, and is important as an early example of a Choir Book, designed so that it could be read by all the members of the choir at once. Choir Books are one of the most well-known types of manuscripts from the late Middle Ages, and indeed, well-beyond that, since they continued to be copied as late as the eighteenth century, becoming larger and more imposing as time went on.

The Olivetan Gradual, formerly Les Enluminures now at the Beinecke Library thanks to one of our clients who fell in love with it and gifted it to them (Yale University, Beinecke Library, MS 1184.)

Selected literature:

Christoph Mackert, “Between Cataloguing In-Depth and Collecting Basic, Standardized Information: Current Trends in Manuscript Description in Germany,” Conference ‘Manuscript Cataloguing in a Comparative Perspective: State of the Art, Common Challenges, Future Directions’, Hamburg, Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures, 7–10 May 2018 https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/written-artefacts/working-groups/permanent-seminar/conference-contributions/files/mackert-text.pdf

Bettina Wagner, “Cataloguing of Medieval Manuscripts In German Libraries: The Role of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Dfg) as a Funding Agency,” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage, vol. 5, no. 1 (2004) https://rbm.acrl.org/index.php/rbm/article/view/225

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!