What does it mean to read an illuminated manuscript today? And more specifically, how do we—as modern readers and viewers—encounter a work like the Roman de la Rose, with all its visual and textual complexity, its resistance to singular interpretation? This blog invites you on a brief journey into the richly embodied, multisensory experience of engaging with Roman de la Rose manuscripts, explored here through the lens of their frontispieces.

Written initially by Guillaume de Lorris around 1230 and completed after his death by Jean de Meun around 1275, the Roman de la Rose is arguably the greatest love story in French literature. What begins as a refined courtly dream vision about the pursuit of love gradually unfolds into an encyclopedic treatise, touching on themes as wide-ranging as philosophy, morality, religion, science, and classical learning. The richness and complexity of the Rose made it one of the most widely read and debated secular texts of the Middle Ages. It sparked the first major literary debate in French history around 1400, and even today, scholars across fields—from literature and art history to philosophy and gender studies—continue to publish hundreds of books and articles each decade in an ongoing effort to interpret its layered meanings.

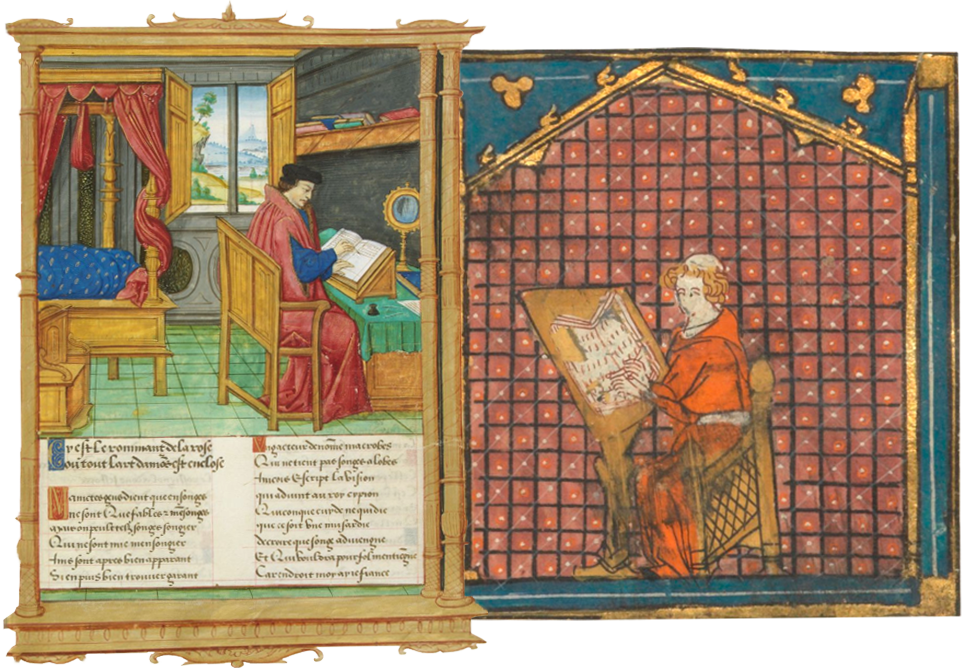

Guillaume de Lorris writing in his study, Morgan Library MS M. 948, Le Roman de la Rose, f. 5, illuminated by the Master of Girard Acaire, Rouen, c. 1525;

Jean de Meun writing on his desk, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, MS 3338, Le Roman de la Rose, f. 29v., illuminated by Jeanne de Montbaston, Paris, c. 1350-60

The Rose was among the most widely copied literary works in the Middle Ages. Even today, 328 manuscripts survive—a staggering number by any standard. Of the 328 manuscripts, 253 are illustrated—an extraordinary figure that speaks not only to the poem’s popularity but also to the central role of imagery in its reception. Geoffrey Chaucer, an avid admirer and translator of the Rose, addressed this visual-verbal integrity in The Book of the Duchess (c. 1368-72), describing an illuminated copy of the poem painted not on parchment but on stone, with its miniatures glossing its text:

And alle the walles with colours fyne

Were peynted, bothe text and glose,

Of al the Romaunce of the Rose.

Geoffrey Chaucer, The Book of the Duchess, Line 331-333

The Walled Garden, British Library Egerton MS 1069, Le Roman de la Rose, f. 1, Paris, c. 1400

As a pastiche of the Rose’s oneiric opening, Chaucer’s narrator awakened within his dream to find himself in a bedroom with unusual walls, on which not only the text of the Rose but also its glosses are painted with “colours fyne” (line 331). These verses seem to imply that the painted glosses are indeed the sequence of miniatures accompanying the manuscript text, typically found in luxurious illuminated copies of the French poem (which Chaucer must have owned). Chaucer aptly chose the Rose to elucidate one particularity of medieval readership, that manuscript illuminations were integral to the meaning-making process, performing the double function of both brightening the pages and enlightening the reader.

Les Enluminures has the honor of presenting several copies of the Rose on the market over the years. In this and the upcoming blog, I highlight two Les Enluminures’ Rose manuscripts and explore how illuminations go beyond merely depicting the narrative but serve as "visual glosses" that transform textual meanings.

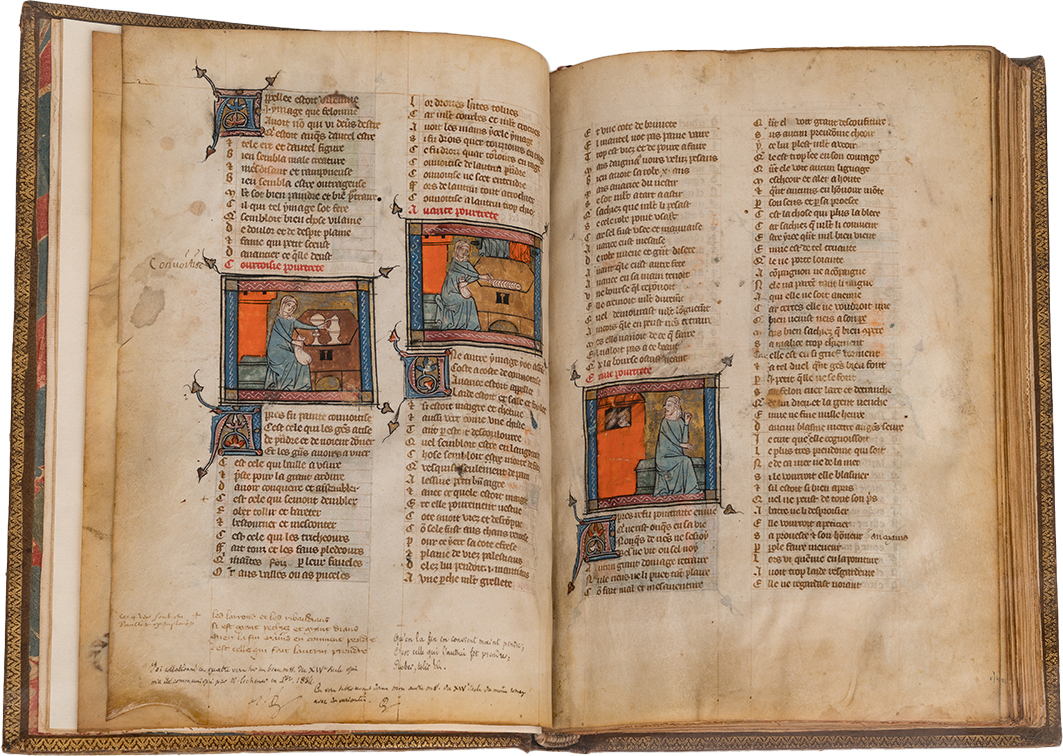

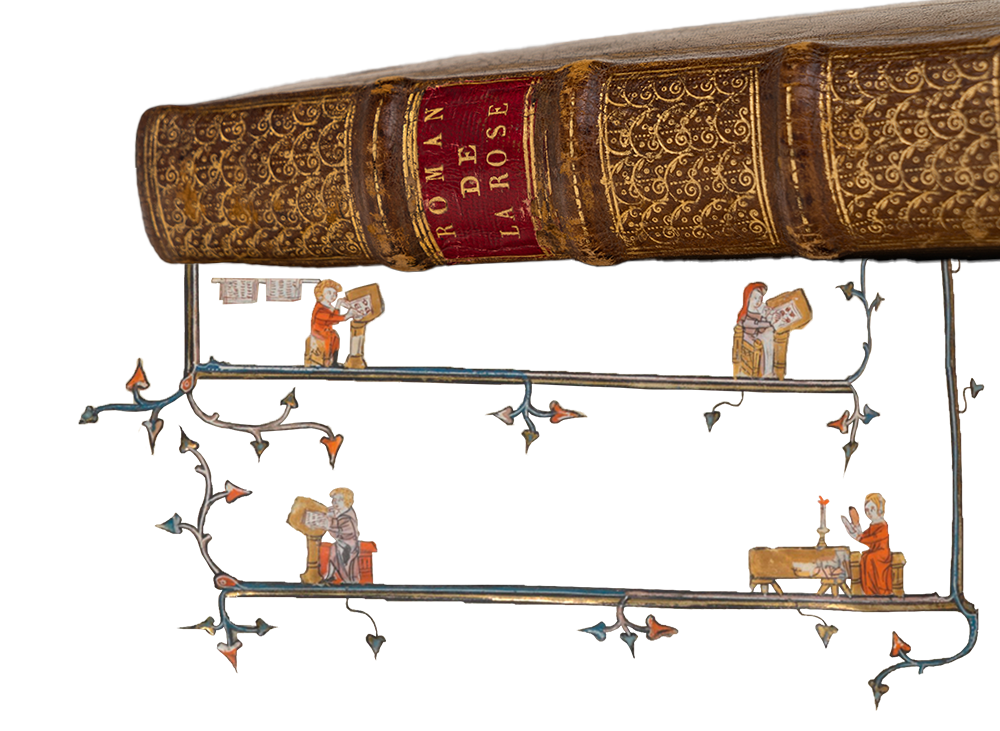

Les Enluminures, IIM 50503, Le Roman de la Rose, France, Paris, c. 1350, ff. 2v-3

The first example, now available for sale on our portal website, is the work of arguably the foremost makers of Rose manuscripts of all time. It is the collaborative effort of Jeanne and Richard de Montbaston, man and wife, who together ran one of the most prolific workshops for vernacular manuscripts in mid-fourteenth-century Paris. We know of more than twenty Rose manuscripts originating from their atelier—far more than those attributed to any other illuminator associated with the poem at any time! The present manuscript features a frontispiece painted by Richard, while the remaining twenty-two single-column miniatures are the work of Jeanne.

Richard took special care to illustrate the opening lines of Guillaume de Lorris’s incipit, where the author tells us that some five years ago, his younger self dreamt that he awakened on a spring morning, dressed, and ventured out of town into a picturesque countryside filled with flowers, birds, and a stream. He eventually encountered the walled Garden of Déduit, a dedicated hunting ground of the God of Love.

Les Enluminures, IIM 50503, Le Roman de la Rose, France, Paris, c. 1350, f. 1

Notably, Richard’s frontispiece emphasizes the desire to enter the garden by foregrounding two key figures: Dangier (at the bedside) and Oiseuse (by the doorway). Their presence cannot be explained literally by the incipit — Oiseuse enters the textual narrative only at verse 520, and Dangier at verse 2825. The significance of representing Dangier and Oiseuse must be symbolic, and I believe they invite us to contemplate upon the very pursuit of meaning. They are gatekeepers aligned with opposing forces of access and denial. Oiseuse, often painted as a keyholder, is the gatekeeper of the Garden of Love. She generously grants the dreamer access, initiating his journey into the allegorical landscape of desire. Dangier, on the other hand, was later described in the poem as one of the doorkeepers of the fortress where the Rose—the ultimate object of desire—is locked away.

Les Enluminures, IIM 50503, Le Roman de la Rose. France, Paris, c. 1350, figures from f. 1

Oiseuse and Dangier control admission or rejection not only into the physical spaces of the garden and the fortress, but into the deeper allegorical domain. If the garden represents the dreamer’s initial entry into the allegorical garden of love, where he is transformed into the Lover through the awakening of desire, then the rosebud signifies the culmination of that desire—not merely as an object of erotic fulfillment, but as the ultimate promise of meaning that the poem claims to enclose.

Les Enluminures, IIM 50503, Le Roman de la Rose, France, Paris, c. 1350, f. 1

This reading is reinforced by the incipit rubric (right above the frontispiece), which frames the Rose as bearers of enclosed meaning. “Here begins the Roman de la Rose, in which the art of love is all enclosed.” The poem’s prologue intensifies this promise of truth – “For as for me, I believe that dreams are full of meaning.” The language of enclosure and eventual revelation invites a mode of reading defined by desire: to enter, to uncover, to interpret.

Les Enluminures, IIM 50503, Le Roman de la Rose, France, Paris, c. 1350, ff. 1v-2

An even greater hint is offered just after the reader flips past the first folio recto. At the very beginning of f. 1 verso, one encounters the closing lines of Guillaume’s prologue, in which he famously invokes the logic of concealment and revelation. “Many things (are said) covertly / That [upon reflection] one later sees more openly.” Here, the allegorical promise—that what is hidden will eventually be revealed—takes on a physical dimension, enacted through the very act of manuscript reading. As the reader moves back and forth between the frontispiece and the prologue, opening and closing parchment folios, covering and uncovering texts and images, the movement of interpretation is made tangible. In this sense, the act of reading the rubric and prologue while looking back at the frontispiece mirrors the dreamer’s own desire to move from outside to inside, from dream to meaning, from covertly to openly. Both Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun later reaffirmed the same promise again and again…