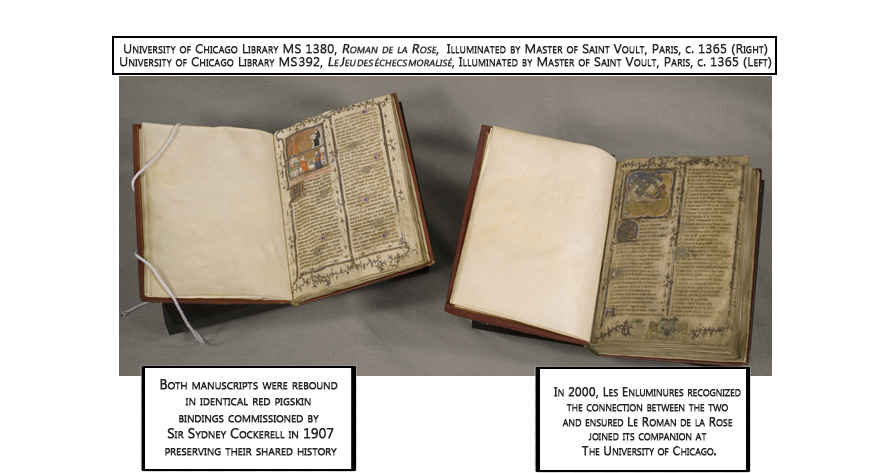

There are many other ways in which illumination can embody meaning—inviting us to read not just with the mind, but through the senses, through gesture, and through the material presence of the parchment folio. The second manuscript example of the Roman de la Rose, now in the Special Collections of the University of Chicago, offers a fascinating glimpse of manuscript erasure and the reader’s body. It is a luxurious copy produced in Paris around 1365, with 43 single-column miniatures attributed to the Master of Saint-Voult.

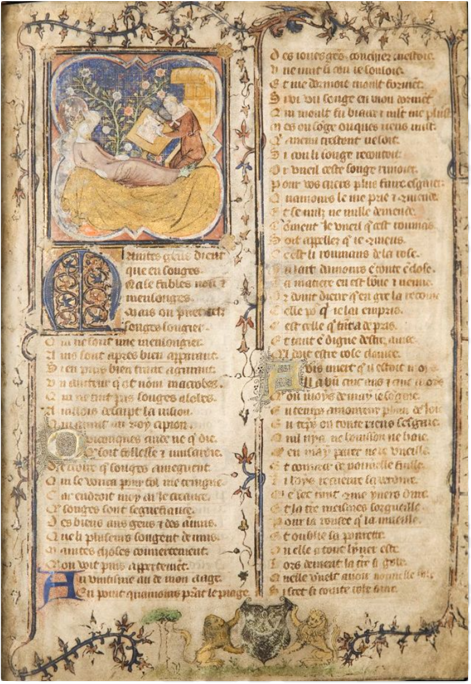

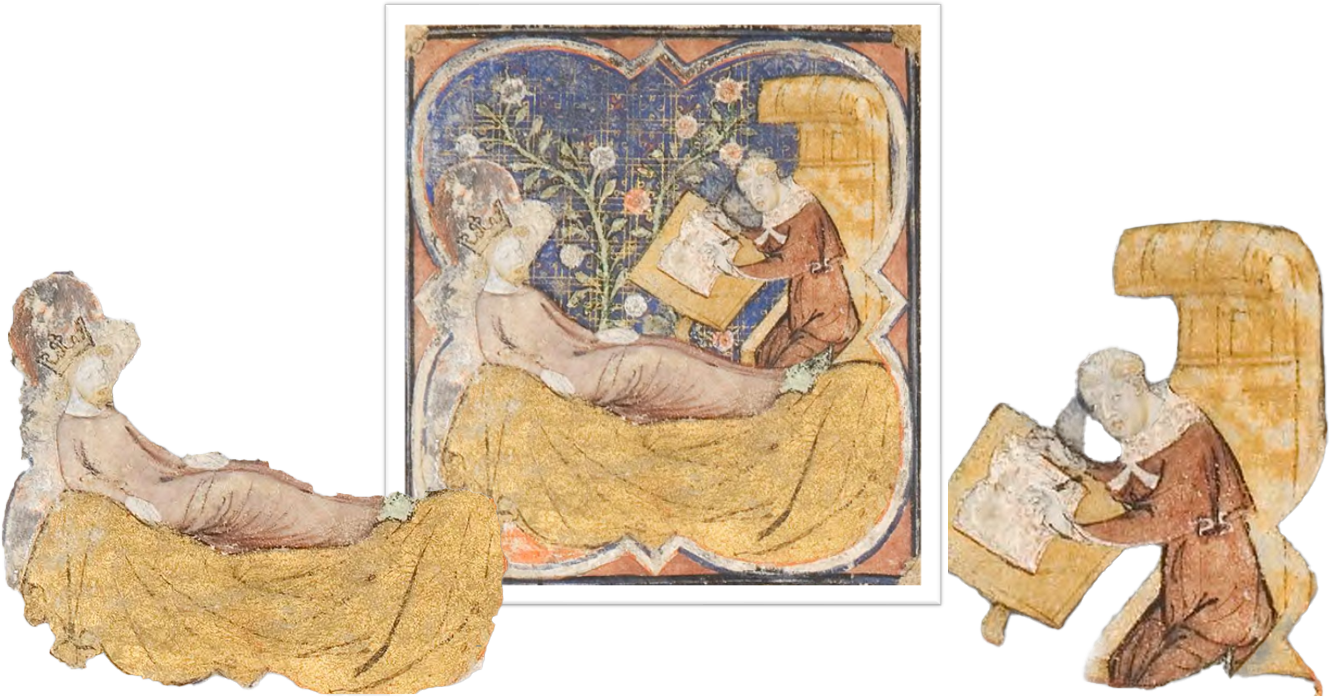

University of Chicago Library MS 1380, Roman de la Rose, f. 1, Illuminated by Master of Saint Voult, Paris, c. 1365

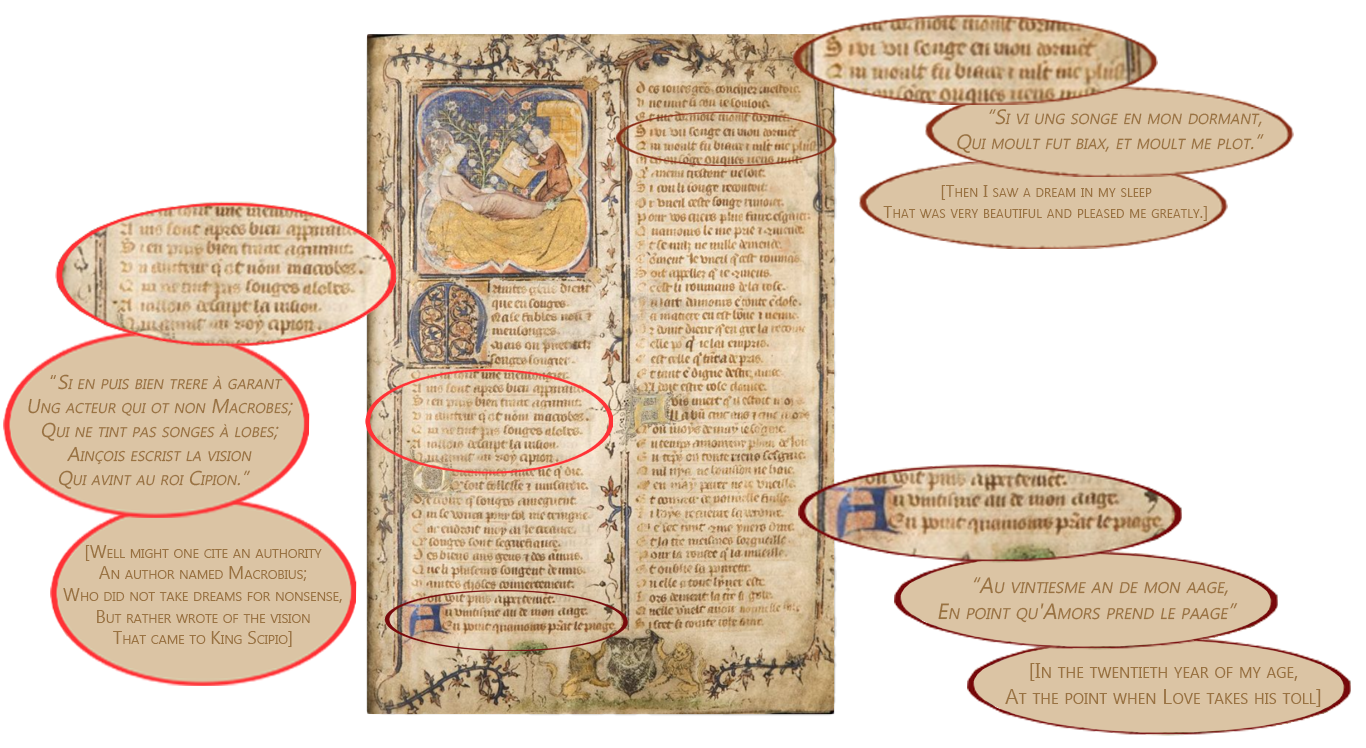

Even before the reader’s eye meets the text, the manuscript insists on being seen: In the foreground of the frontispiece, a crowned figure lies casually on his bed, eyes closed. At the foot of the bed sits a second figure—a slightly older man with a tonsure, dressed in a scholar’s robe. He leans toward an open codex on a scribal desk, holding a quill in his right hand and a knife in his left. Interestingly, the knife rests directly on the page, as if he’s in the act of scraping away something he’s just written. Between the bed and the desk, a blooming rosebush stretches upward, its red and white blossoms curling toward both the sleeper and the writer.

The identities of these figures become clearer as the reader turns to the textual opening. The prologue, in the voice of Guillaume de Lorris, reflects on the truth concealed in dreams, citing Macrobius’s Commentary on Cicero’s Dream of Scipio. At first, the sleeping figure appears to be Scipio himself. But then, a first-person narrator steps in, as an older poet/narrator recalling a dream he had at the age of twenty. The sleeper thus acquires a dual identity: both Scipio, whose dream foregrounds the poem’s meaning, and the poet-dreamer, whose romantic vision will unfold in the written narrative that follows.

As we know, the poet’s dream centers on the desire for the Rose—symbolizing both the beloved as the object of erotic longing, and the hidden meaning of the poem as the object of intellectual pursuit. More specifically, the image encapsulates acts of looking and reaching toward the body. The rose stands in for bodily desire, its branches leaning toward the sleeper’s left hand, which is subtly raised as though trying to grab the stem. The seated poet—possibly modeled on Jean de Meun, himself likely tonsured—turns toward his younger self and squints toward the rose as he leans into his work. His posture suggests both introspection and physical engagement – a gesture of remembering, revising, and reexamining the self through the act of writing. Notably, later in the poem, the very gestures of “shaking the rose” and “writing with a pen” are used as metaphors for sexual union—that is, for the fulfillment of desire.

The frontispiece thus visually anchors the poem’s central themes: dreaming, desiring, and the act of interpretation through writing.

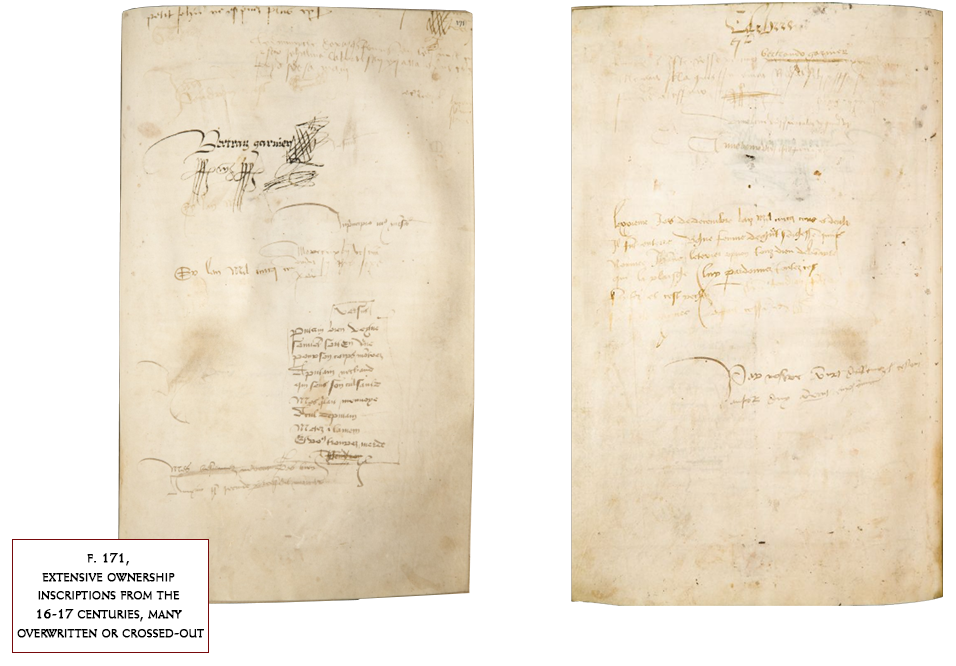

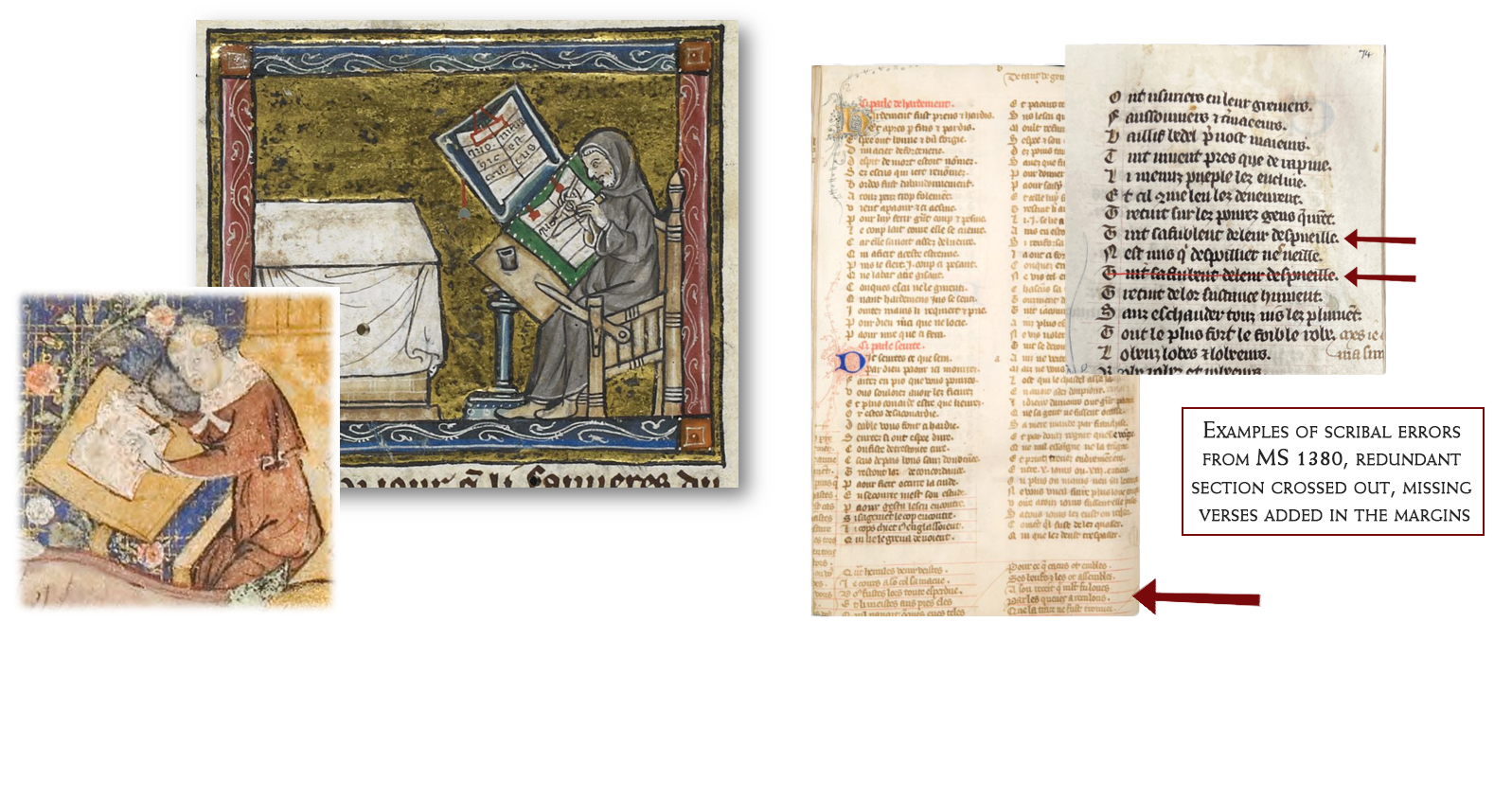

The knife resting on the page adds a further dimension. In medieval manuscript culture, the quill and knife were standard tools: the quill for writing, the knife for scraping away errors. Though authorship and copying differ conceptually, both share the same embodied gestures. The frontispiece, then, may also allude to the scribe who made this manuscript. And interestingly, the scribe made an unusual number of mistakes for such a luxury manuscript. In later folios, we find extensive erasures, crossings-out, and overwriting, even a large missing passage added in the margins. This opens up a playful possibility. Since scribes typically completed the text before artists added miniatures, and artists painted by reading instructions and rubrics, if not the poem itself, written out by the scribe, perhaps the Master of Saint Voult deliberately depicted the author figure scraping the page, to subtly poke fun at the error-ridden text copied by his absent-minded colleague.

A hermit copying a manuscript, from L’Estoire del Saint Graal (British Library Royal MS 14 E III), f. 6v, France (Saint-Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315 – 1325. Note how he is depicted writing, instead of erasing

Erasure, however, was not limited to production. It was common in readership and ownership. On this very first folio, part of the border has been scraped away to insert a later coat of arms. Deeper in the manuscript, we find many ownership inscriptions that have been erased and replaced throughout the sixteenth and the twentieth century. So, the frontispiece becomes a self-aware image—a visual pun that encapsulates the life of the manuscript as an object of desire, touched, altered, and reinterpreted across time. It draws attention not only to the acts of dreaming and writing, but also to the manuscript’s ongoing object history and the many bodies who have shaped it. It invites us, as readers and viewers, to engage not only intellectually but bodily – with a page that is meant to be interpreted, that is, by seeing, touching, erasing, and writing on a space where meaning arises beyond the text itself.