“You naturally seek out things Italian, and so do we and our friends”

-- E M Forster, A Room with a View

By 1908 when Forster published A Room with a View, an enjoyment of premodern Italian art formed a proverbial element of the British middle classes. Yet this passion reflected less than a century of consensus, and had not developed organically, but was deliberately conceived. Driven by some combination of inspiration and desperation, two men came together to teach the late Georgian English that premodern Italian art was desirable and that illumination could be thought of as miniature paintings, and that Italian miniatures could therefore be collected just like panel paintings.

Portrait of William Young Ottley by William Riviere

William Ottley (1771-1836) was born to a baronet (and governor of Dominica)’s daughter and a colonial officer. Defying both political instability and current fashions in art, in 1791 Ottley traveled to Rome to study premodern sculpture and painting for a decade. Returning home with trunks of inventory in 1801, Ottley commenced his genteel career as an art dealer. Soon thereafter he leveraged improvements in the technology for printing images to begin a long and influential series of illustrated works and catalogs that educated the reading public about Italian art. Only at the end of his life did Ottley become Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum.

Title pages of Ottley’s printed series of illustrated works and catalogs

In the same year, the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 provided a path for enslaved people through much of the empire to obtain their freedoms, and the Ottley family fortune, and the fortunes of many of Ottley’s clients, relied either directly or indirectly on plantation agriculture and enslaved labor. Suddenly Ottley needed a regular job at the Museum, and many of his clients too might have found that miniature paintings continued to be affordable despite their newly straitened finances. Almost a decade before Ruskin’s shoes trod the stones of Venice, the English artistic taste had taken a premodern Italian turn thanks to Ottley.

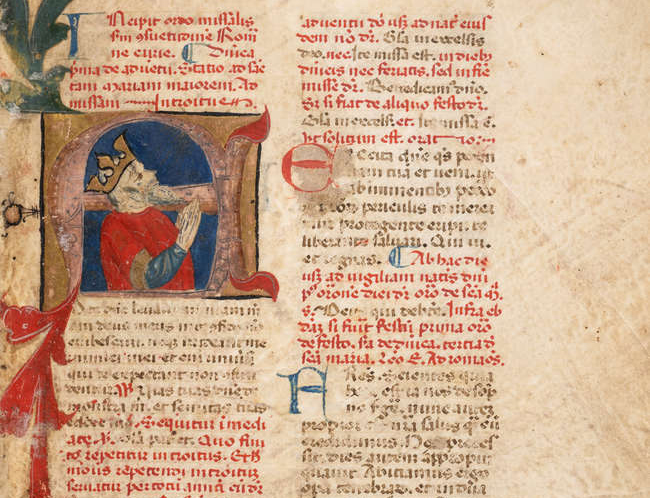

Missal (use of Rome) (TM1339), Lombardy, (Milan?) c.1430, f. 102

Luigi Celotti (1759-1843) was a well-born Italian priest who maneuvered through both Revolutionary and then Napoleonic Italy. Between these cataclysms, enormous numbers of Italian monasteries and churches were closed, leaving countless clergy suddenly without employment or housing, and rendering books and art of all kinds vulnerable to theft or fire sale. Meanwhile wealthy families sold off libraries in attempts to remain solvent during these uncertain times. While his earliest recorded trip to London began in 1816, Celotti seems already to have been known in the antiquities business there and so must have begun developing his English network earlier (Eze, 2010).

Christie's auction room in London: This engraving was published as Plate 6 of Microcosm of London (1808)’

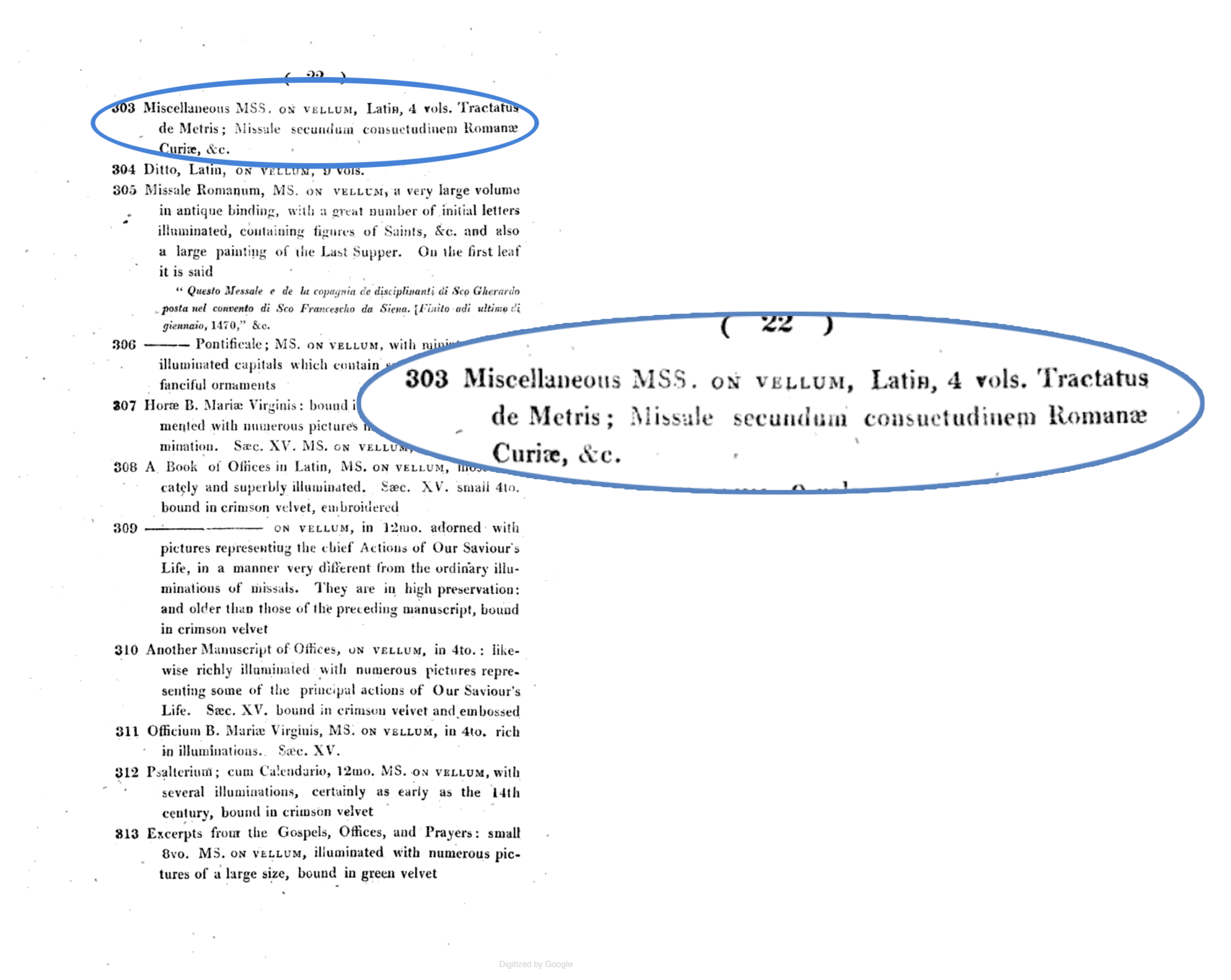

He sold at Sotheby’s beginning in 1819, and at the 1821 sale at which TM1339 changed hands he offered books from two large Venetian collections. Although Celotti continued to sell codices through the 1820s, when the priest teamed up with Ottley, he switched auction houses and concentrated on a new type of art: “the first auction dedicated solely to illuminated manuscript cuttings was the Celotti sale at Christie's, 26 May 1825; the catalogue was written by William Young Ottley (1771-1836), who bought extensively at the sale; and Ottley's own collection was sold about a decade later [in] 1838” (Kidd, 2020).

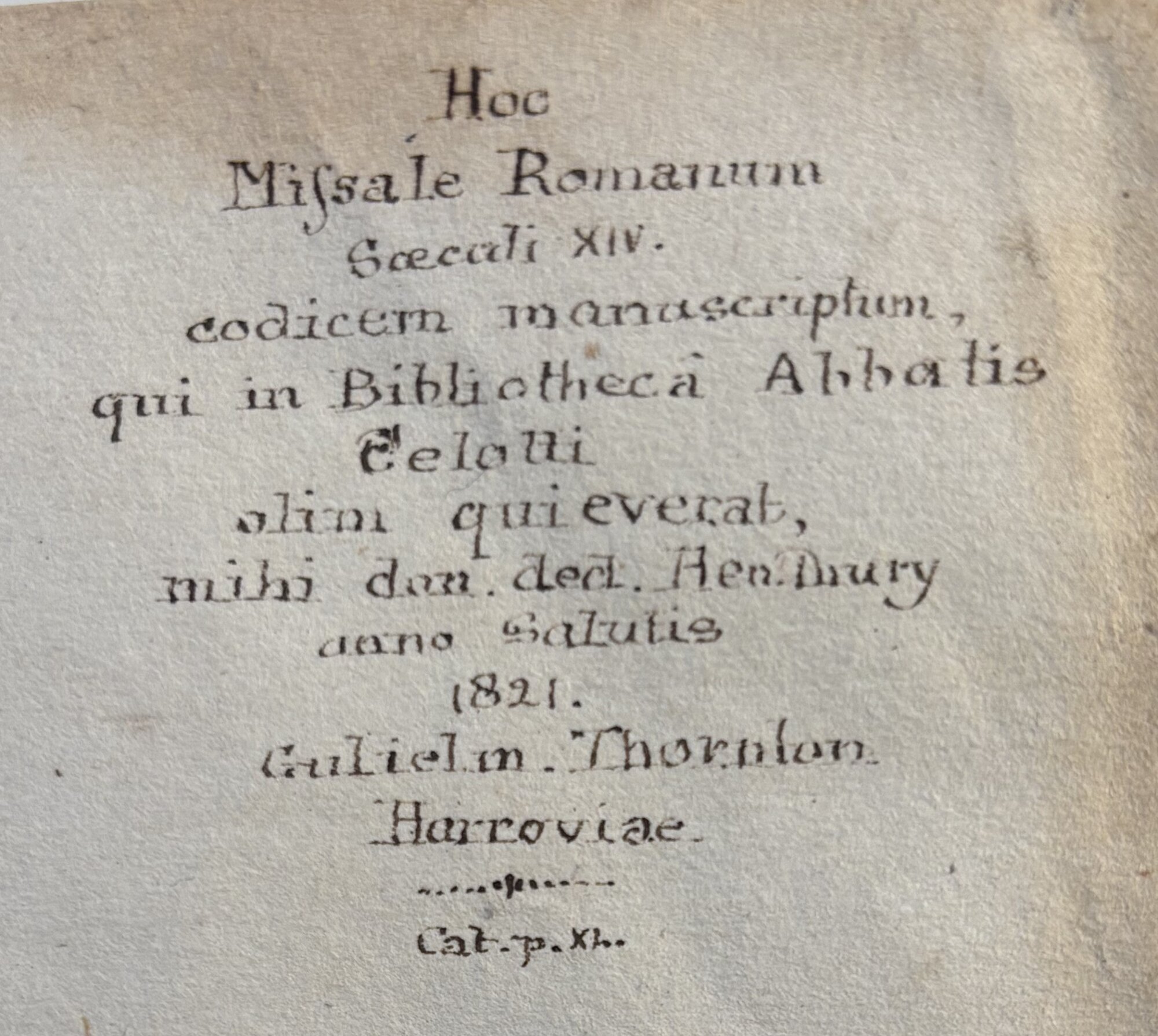

Ownership and gift inscription, TM1339

Reverend Henry Drury (1778-1841), a classicist who taught at Harrow School from 1801 to his death, purchased two classical volumes from Celotti’s 1821 sale, in addition to the lot in which he acquired TM1339 (Eze, 2010). As classical works would have been both of personal interest and use to him in teaching, one must guess that his attraction to Lot 303 was the Tractatus de metris rather than the small missal.

Drury’s interest in manuscripts was textual, rather than artistic as was Celotti’s and Ottley’s. Indeed, the humble art of TM1339 may explain why this volume passed through Celotti’s hands without, apparently, also finding its way into Ottley’s. While here at Text Manuscripts we might appreciate how perfectly fitting such understated decoration was to a missal made for the humble Franciscans, it may have held little appeal to the pair of Georgian art dealers. Even Drury’s textual interest focused elsewhere, on classical and pedagogical material. Thus, Drury gave TM1339 away to William Thornton*, its liturgical text of no more interest to him than its illumination. In the event, neither Drury nor Thornton may have realized that they took part in England’s historic turn towards medieval Italian art. Nevertheless, Thornton recorded that this book was among Celotti’s inventory, and therefore we can recognize today that TM1339 marks one small part of that momentous process.

Missal (use of Rome) (TM1339), Lombardy, (Milan?) c.1430, f. 1

*In one of history’s minor ironies, E. M. Forster may have been distantly related to Thornton, but the historical research to investigate this fully remains to be done!

Bibliography:

Eze, Anne-Marie. “Abbé Luigi Celotti (1759-1843): Connoisseur, Dealer, and Collector of Illuminated Miniatures,” Unpublished PhD dissertation, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 2010.

Kidd, Peter, “Master BF and the Holford Collection,” (2020) https://mssprovenance.blogspot.com/2020/06/master-bf-and-holford-collection.html