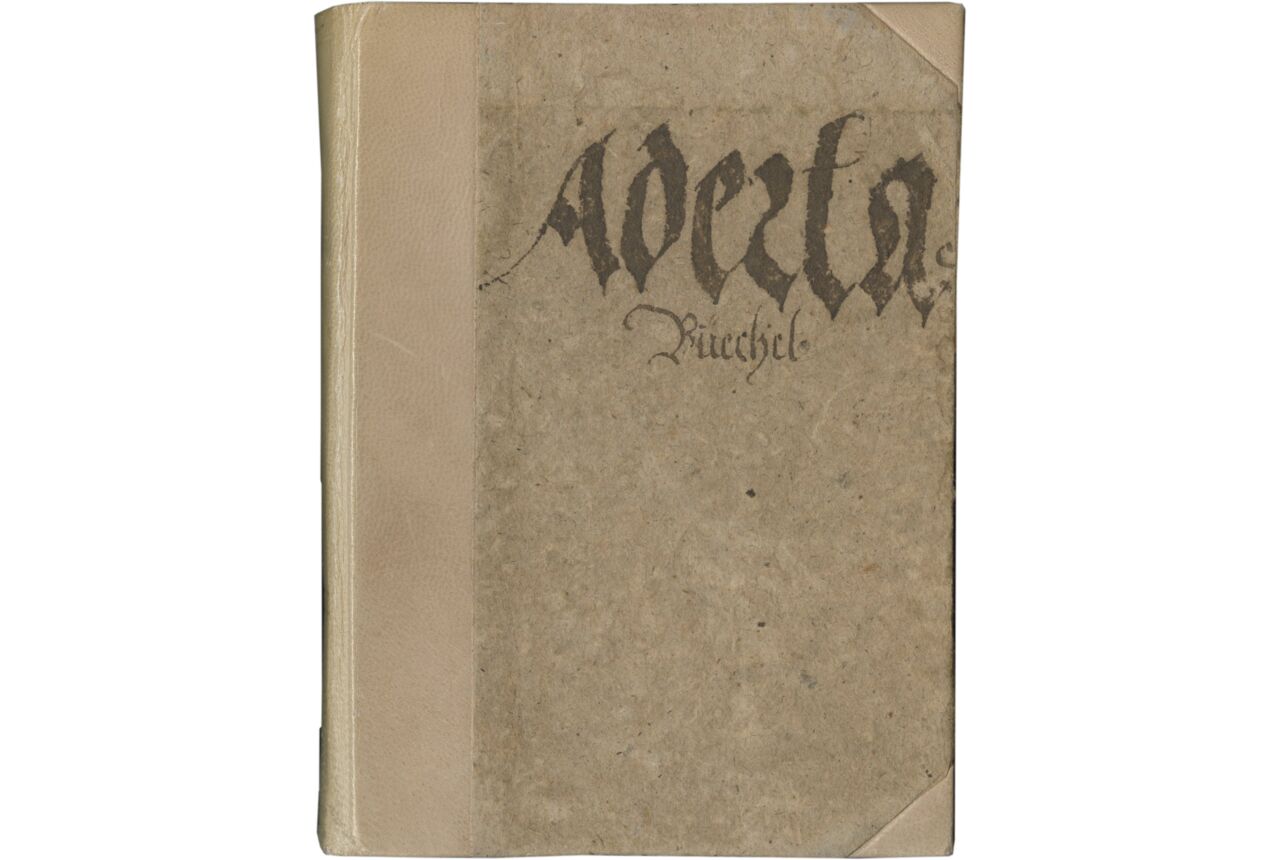

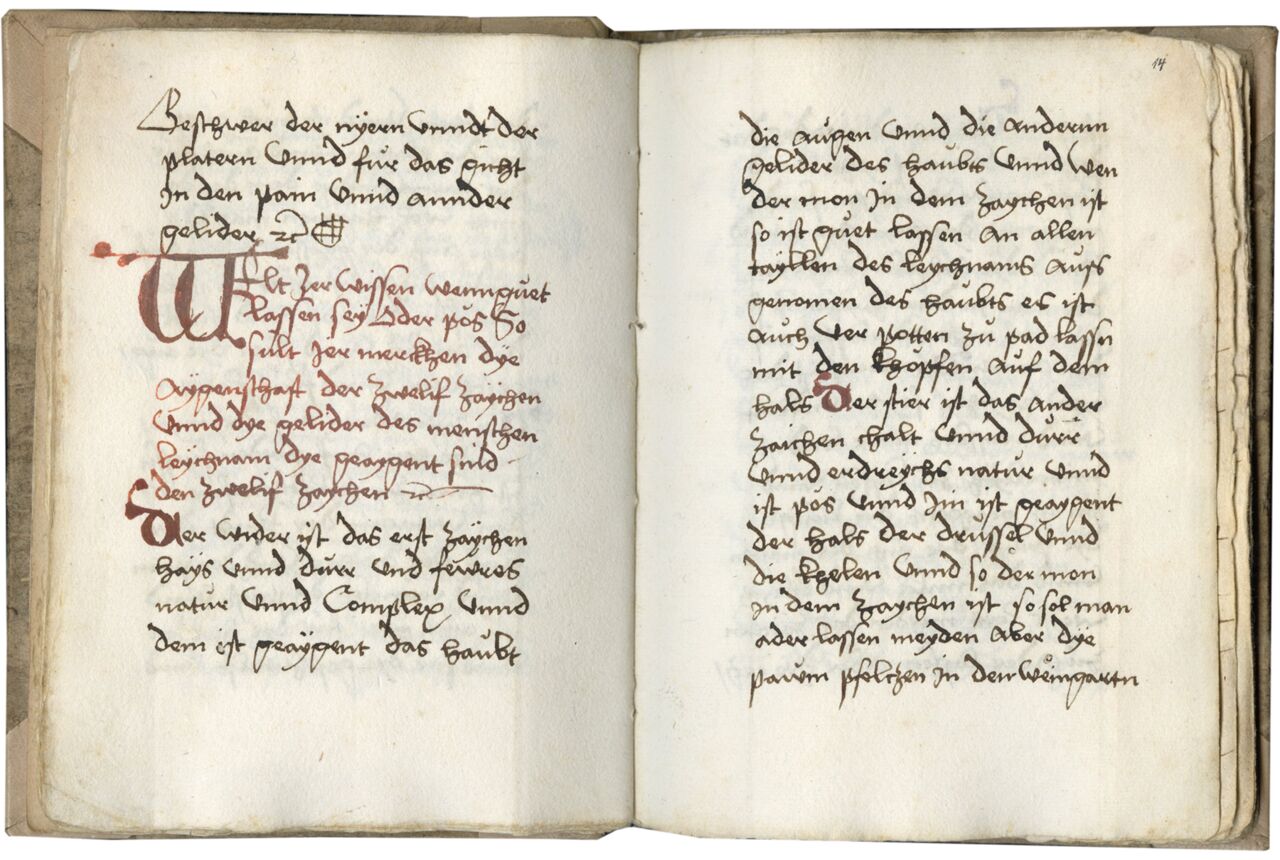

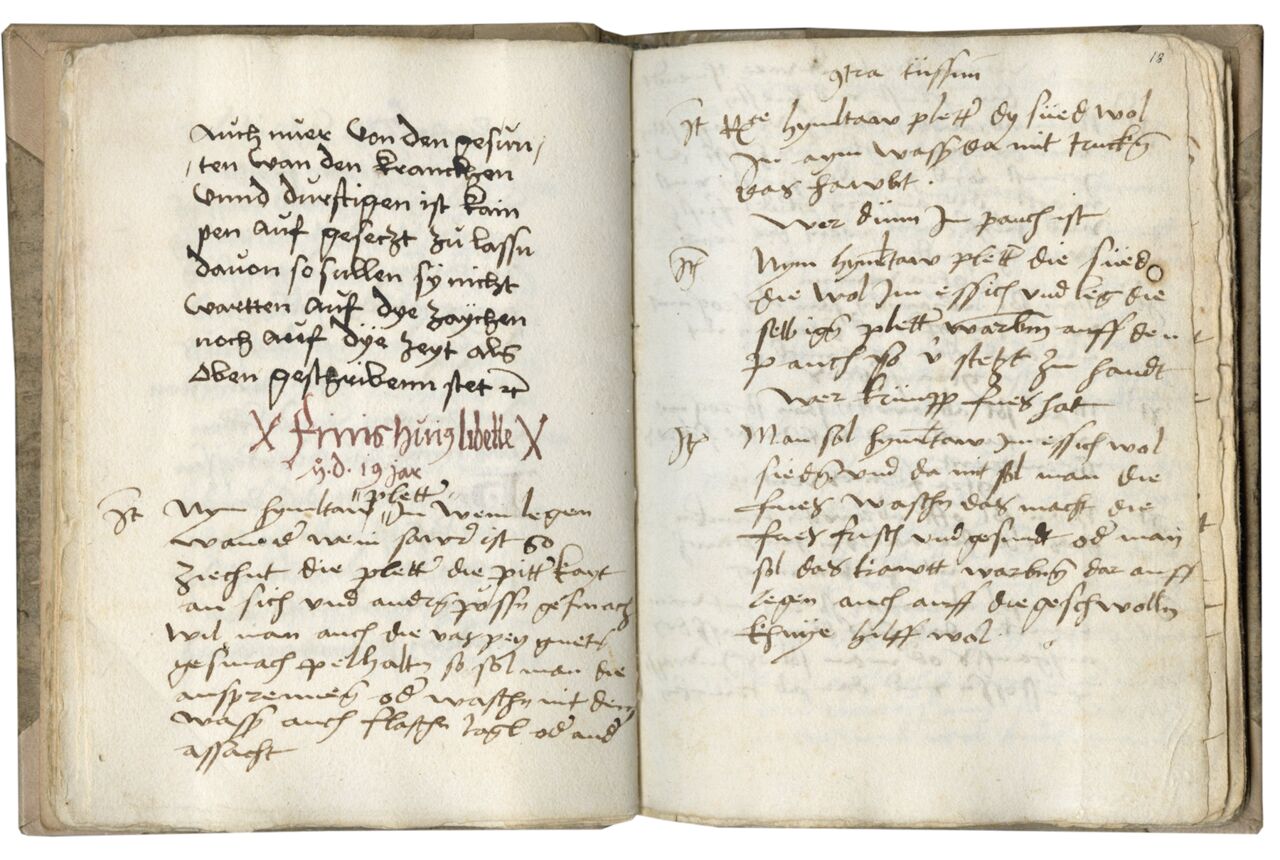

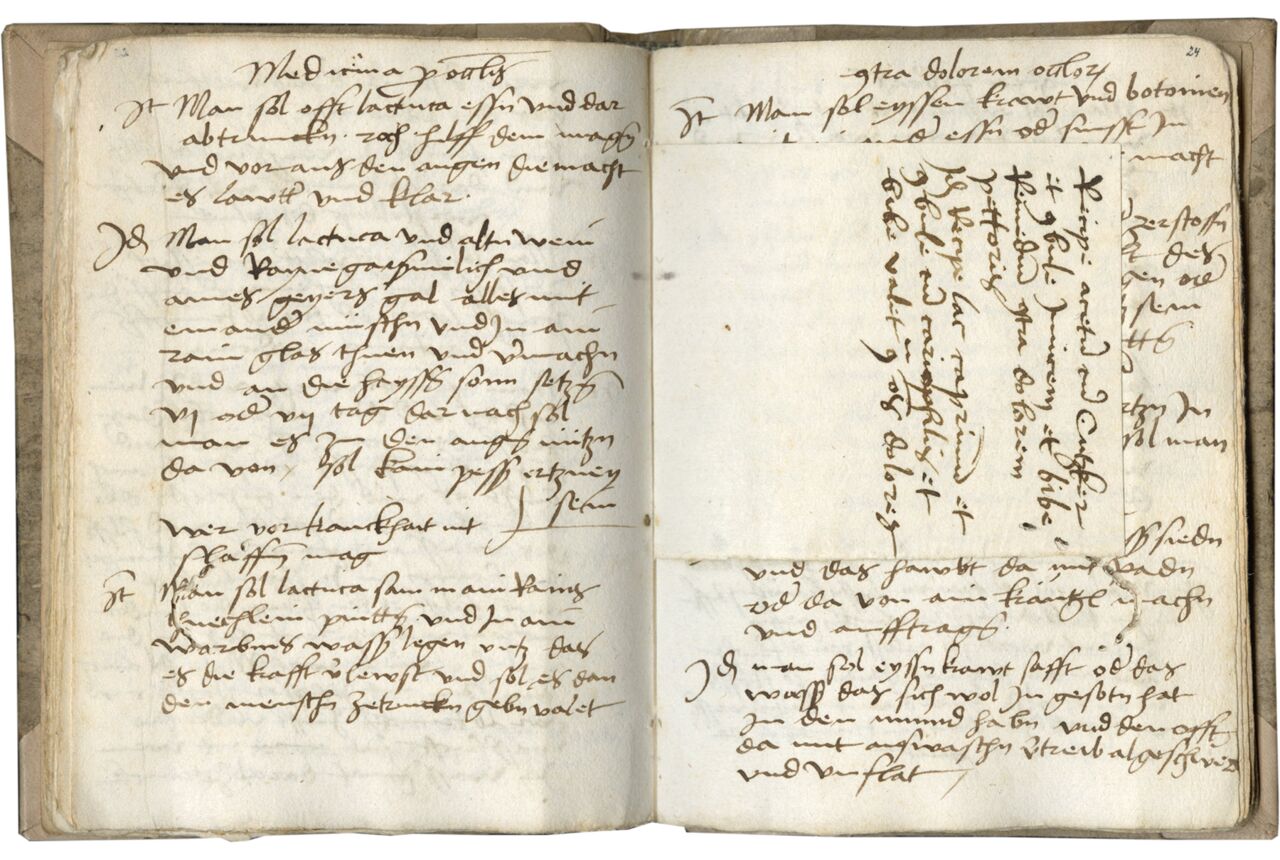

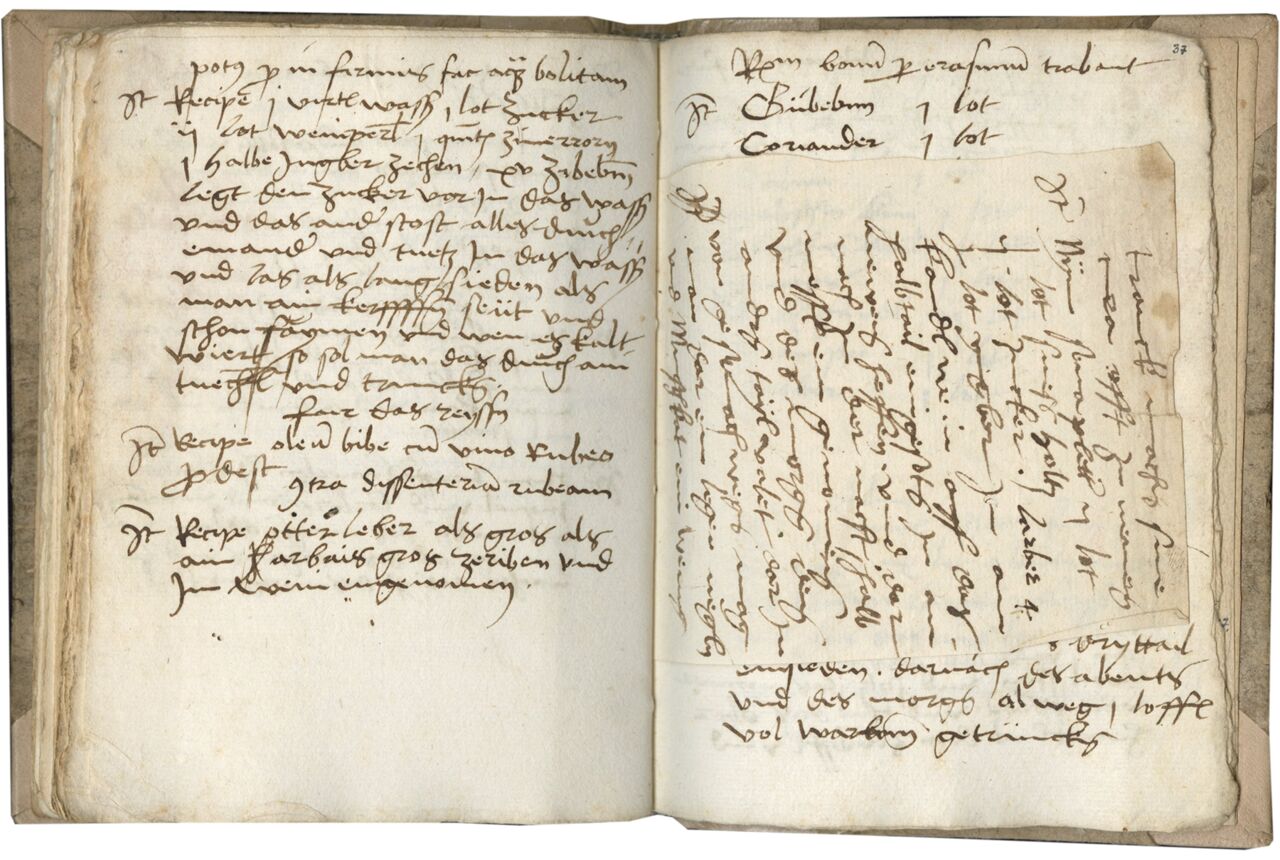

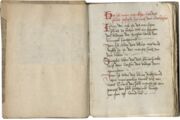

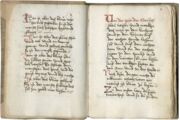

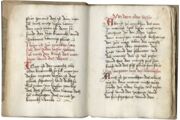

i (modern) + 41 + i (modern) folios on paper, watermark, unidentified scales within a circle, modern foliation in pencil, 1-41, complete (collation i19[one singleton pasted to the end of the quire] ii22), several small strips of paper bound in between leaves containing contemporary text, no catchwords or signatures, no ruling (justification variable, c. 110 x 70 mm. on ff. 1-17; in the rest of the manuscript the text extends to the edges of the leaves), written by two different scribes: ff. 1-17v written in 1519 by scribe 1 in dark brown ink in a spiky gothic hybrid bookhand in single column on c. 16 lines, rubrics and initials in red, ff. 17v-41 written in 1531 by scribe 2 in brown ink in gothic cursive bookhand in single column with up to 24 lines, very minor signs of wear, in overall excellent condition. In modern half-binding of beige-colored calf, using the original paper cover with the title “Aderla[ss] Büechel” inscribed in black ink, flat spine blind-tooled with double fillets, modern paper pastedowns and flyleaves, in overall excellent condition. Dimensions 147 x 110 mm.

The importance of blood to all aspects of medieval life continued into the Early Modern era. Theories about blood, and the importance of bloodletting, were essential to medicine in the sixteenth century. This very important dated medical manuscript includes a text on bloodletting; its introductory section presents a uniquely practical approach to the subject of phlebotomy (and is apparently known only in this manuscript). Equally significant are the medical recipes that follow. The manuscript formerly belonged to the renowned German medievalist and collector, Dr. Gerhard Eis.

Provenance

1. The bloodletting text on ff. 1-17v was copied in 1519 according to the explicit on f. 17v: “Finis huius libelle / M. D. 19jar.” The scribe may have started the work in 1516, as suggested by the title “Regimen minucionum 1516” inscribed in the hand of the scribe on a piece of contemporary paper that has been later pasted to the front flyleaf. The other two texts, a German herbarium and medical recipes on ff. 18-40, were copied by another scribe, and completed in 1531, as suggested by the mention “1531” on f. 40 (Eis, 1943; Eis and Schmitt, 1967).

Gerhard Eis, who owned the manuscript from 1939 onwards (see below), localized it in southern Bohemia. The herbarium and medical recipes, copied in 1531, include a remedy for festering ulcers (“für den affl”) on f. 32, by a certain Hieronymus von Kienberg. According to Eis, the otherwise unknown author lived in the central Bavarian region, most likely southern Bohemia, where the manuscript was made (Eis, 1943, pp. 100 and 112, and Eis, 1953, p. 225). Josef Werlin, who studied the manuscript when it was in the Eis Collection, confirmed this localization, based on both linguistic features and the argument of Hieronimus von Kienberg, which likely refers to an origin rather than an established family name (Werlin, 1961, p. 763). Kienberg is located near Krumau (Český Krumlov) in the southern Bohemian Forest on the Vltava River in South Bohemia, today southwestern Czech Republic.

2. In 1939 belonged to Josef Dolzer(?); see below.

3. MS 22 in the collection of Dr. Gerhard Eis (1908-1982), German medievalist, medical historian, and collector (see Online Resources); his book label is pasted inside the front cover. Dr Eis was given the manuscript as a gift on 4 January 4, 1939 by his student, “1938/1939 als Geschenk von meinem Schüler Josef Dolzer[?]/Asang erhalten.” The mention of this gift is followed by a long list of publications by Eis and others concerning the manuscript, on the recto and verso of the flyleaf.

Text

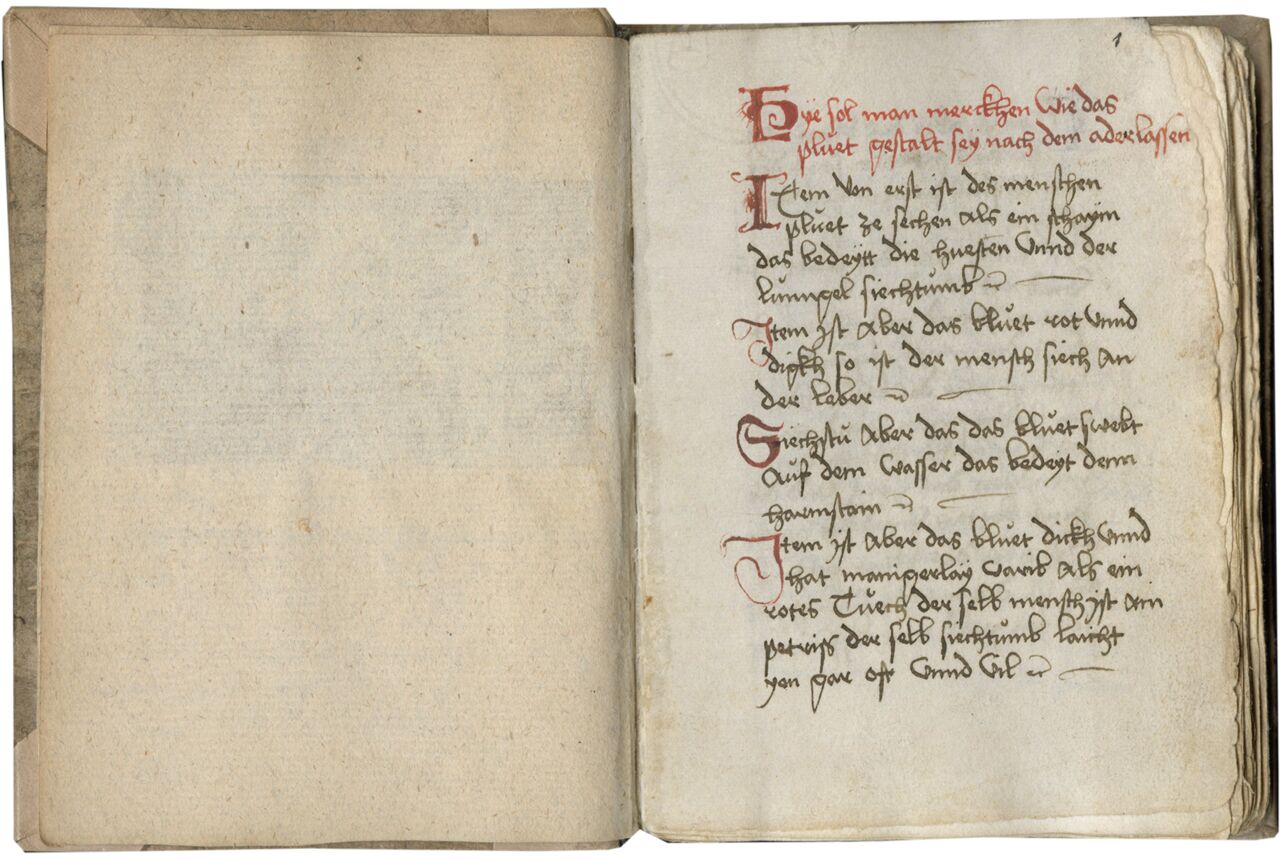

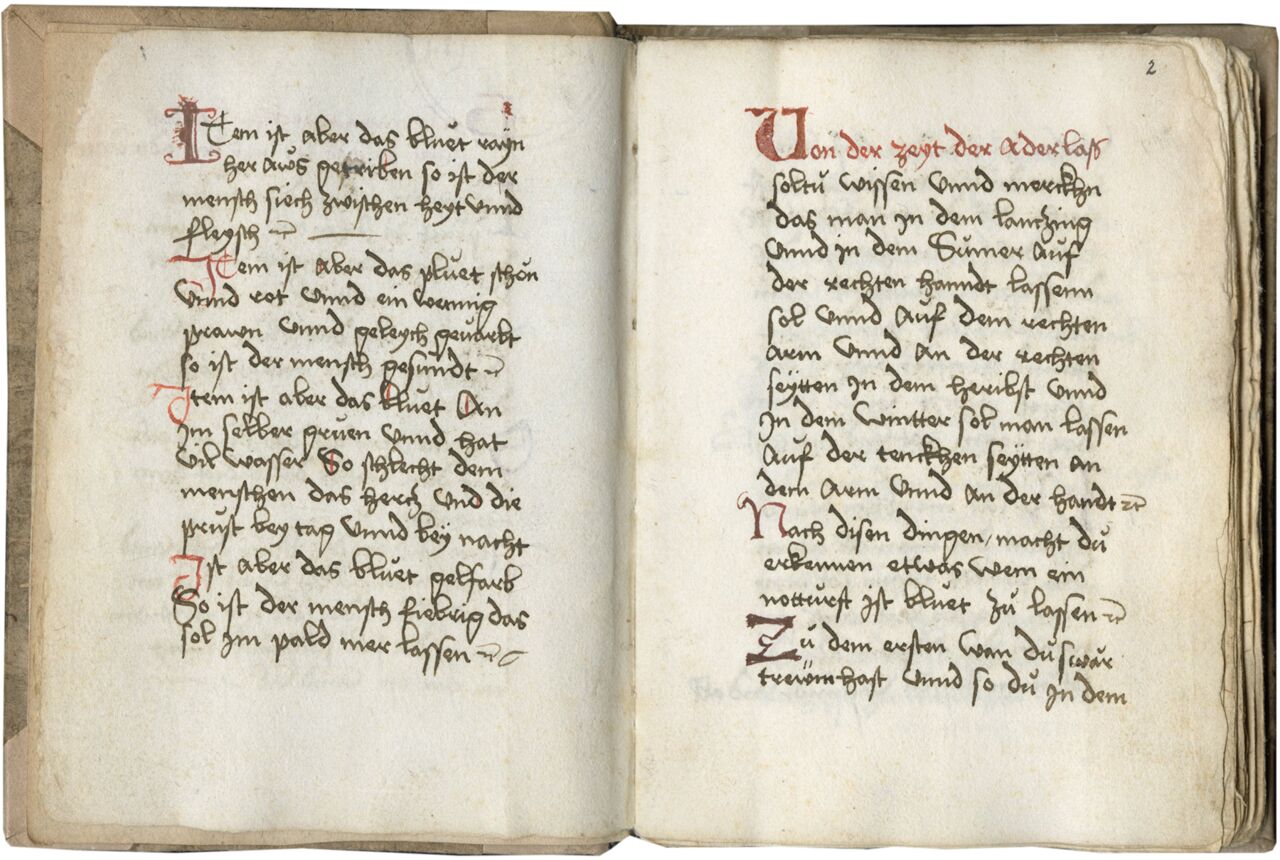

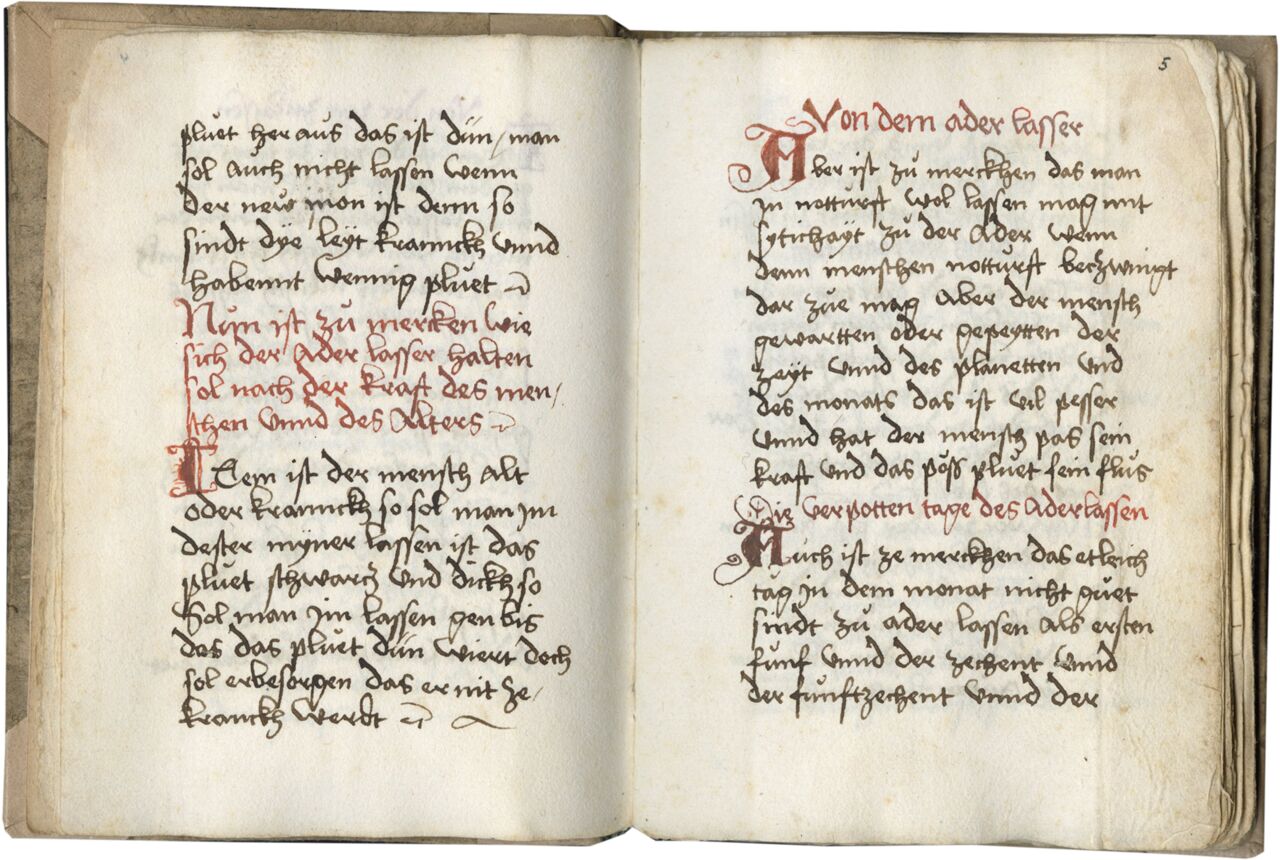

ff. 1-17v, ff. 1-6v, [part one], Hye sol man merckhen wie das pluet gestalt sey nach dem aderlassen” (Here you should notice how the blood looks after the bloodletting), incipit, “Item von erst ist des menschen pluet ze sechen als ein schaym ... Ader lass bechuet den menschen vor siechtumb unnd erhebt dem menschen sein stym. Deo gracias”; ff. 7-17v, [part two, divided into two chapters that provide the rules of the bloodletting process (presented in the form of lists)], ff. 7-13v, [the first chapter contains the medical prescriptions], Von dem aderlassen ist zu merkhen, das all adern dye alenthalben von dem haubt gen ... nach essenns” [cf. Werlin, p. 765; Sudhoff, p. 186], incipit, “Dye ader mitten an dem stirm ... in dem pain unnd annder gelider etc.” [cf. Sudhoff, pp. 187-188]; ff. 13v-17v, [the second chapter contains the astrological prescriptions], Welt jer wissen wenn guet lassen sey oder poss, So sult jer ... zwelif zaychen [cf. Sudhoff, p. 214], incipit, “Der wider ist das erst zaychen ... als oben geschribenn stet etc.” [cf. Sudhoff, pp. 214-215];

Treatise on bloodletting, divided into two parts, ff. 1-6v and ff. 7-17v; see Eis and Schmitt, 1967 (an edition of our manuscript; not available for consultation for this description); the first part of the text in our manuscript previously edited by Josef Werlin, 1961, pp. 764-766; the text of the second part edited by Karl Sudhoff, 1914, pp. 186-188, 214-215 (based on manuscripts in Munich). The first part of the treatise begins on f. 1r-v with a list of descriptions of the appearance of blood after bloodletting and of the diseases that can be inferred from it if the quality and color have changed; this is followed by information about bloodletting in different seasons, taking into account the climate, and brief explanations about the patient’s behavior after the treatment, according to his age and constitution, and about the times when the surgical procedure is unsuitable or prohibited.

ff. 17v-41, Medical recipe collection in German; [f. 41v, blank].

The first section, the Herbarius, includes an extensive collection of recipes for one hundred and twelve different ailments, many provided with headings, and recommending native plants for the treatments, followed immediately by a heterogeneous collection of twenty-eight recipes with more detailed instructions, sometimes even with precise measurements, and also including animal and mineral remedies. Edited in Eis and Schmitt, 1967 (not available for consultation); see also Eis, 1943 and Eis, 1939, plague recipes, recorded in Appendix 3 in Eis 1939 (see Literature).

The bloodletting treatise on ff. 1-17v provides a very detailed description of phlebotomy, in two sections. The second section of this text on ff. 7-17v contains the medical and astrological prescriptions that were the basis of all medieval bloodletting instructions. It begins with listing twenty-seven veins and the medical interest of each for bloodletting treatment. Gerhard Eis published the list in 1953 (Eis, 1953; the subject of his article is another bloodletting manuscript in his collection, Cod. 54, containing the Latin treatise Utilitas venarum pro minucione; for our manuscript see pp. 225-226). In our manuscript this part begins with “Dye ader mitten an dem stirm...” (f. 7), describing the vein in the middle of the forehead, which is good for treating swollen and irritated scalps, madness and insanity, a disturbed or damaged brain, as well as squints, sores, rashes, and the dark circles around the eyes or ocular inflammation. The text contained in our manuscript is very close to that edited by Karl Sudhoff, differing mainly in linguistic aspects. Sudhoff’s edition of the first chapter (cf. ff. 7-13v in our manuscript) is based on Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, cod. Mon. lat. 18294, ff. 283-284, made in 1471, and the second chapter (cf. ff. 13v-17v in our manuscript) is based on Munich, Hofbibliothek, cod. lat. 700, ff. 86v-87, made in 1458.

The first part contained in our manuscript on ff. 1-6v shows no similarity to any Latin or German bloodletting text edited by Sudhoff, and according to Werlin no other bloodletting text describes additional rules for this procedure in as much detail as our manuscript (Werlin 1961, p. 763). Werlin states that the author of this introduction certainly had medical training and that he either copied the text from a now lost Latin or German exemplar or composed it himself using a number of sources (Werlin 1961, p. 764). This section provides descriptions of the appearance of blood and conclusions that can be drawn from them. It explains how different seasons should be taken into consideration in bloodletting, hot or cold weather, as well as old age, and how one should proceed in the days following bloodletting (eat little on the first day, be happy on the next day, rest on the third day, take medicine on the fourth day, and take medicine again on the fifth day, f. 6).

The most common healing method of medieval surgeons was bloodletting. It had become increasingly popular since the fourteenth century, and illustrations of bloodletting were often included in calendars. Signs of the zodiac were drawn on the body parts, thus instructing the correct time for drawing blood from each part of the body. The treatise in our manuscript advises that one should not perform bloodletting on the first or last five days of the month, on the tenth, fifteenth, or twentieth days of the month, on April 18th, August 1st or New Year’s Eve, for otherwise one shall die a terrible death (f. 5r-v).

Literature

Bildhauer, B., Medieval Blood, Religion and Culture in the Middle Ages, Cardiff, 2006.

Bildhauer, Bettina. “Medieval European Conceptions of Blood: Truth and Human Integrity.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 2013, pp. 57-76.

Eis, G. “Das Deutschtum des Arztes Albich,” Zeitschrift für deutsche Philologie 64 (1939), pp. 174-209.

Eis, G. “Ein deutscher Herbarius von 1531,” Deutsche Volkforschung in Böhmen und Mähren, 1943, pp. 97-112.

Eis, G. Gottfrieds Pelzbuch: Studien zur Reichweite und Dauer der Wirkung des mittelhochdeutschen Fachschrifttums, Südosteuropäische Arbeiten 38, Brünn/München/Wien, 1944, p. 12.

Eis, G. “Utilitas venarum pro minutione,” Sudhoffs Archiv für Geschichte der Medizin und der Naturwissenschaften 37 (1953), pp. 223-229.

Eis, G. “Heilmittel gegen Harnleiden aus altdeutschen Handschriften,” Medizinische Monatsschrift 7 (1953), pp. 803-806; see especially pp. 803, 805 (no. VI).

Eis, Gerhard and Wolfram Schmitt, Das Asanger Aderlaß- und Rezeptbüchlein (1516-1531), Veröffentlichungen der Internationalen Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Pharmazie N.F. 31, Stuttgart 1967.

Giese, M. “Das ‘Pelzbuch’ Gottfrieds von Franken: Stand und Perspektiven der Forschung,” Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur 134 (2005), pp. 294-335.

Keil, G. “Asanger Aderlaßbüchlein,” Verfasserlexikon (1978), p. 507.

Riha, O. Das Arzneibuch Ortolfs von Baierland: Auf der Grundlage der Arbeit des von Gundolf Keil geleiteten Teilprojekts des SFB 226 'Wissensvermittelnde und wissensorganisierende Literatur im Mittelalter' zum Druck gebracht, eingeleitet und kommentiert von O. R. (Wissensliteratur im Mittelalter 50), Wiesbaden 2014, p. 30.

Sudhoff, K. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Chirurgie im Mittelalter, vol. 1, Leipzig, 1914, pp.

Available online:

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://ia800900.us.archive.org/9/items/beitragezurgesch01sudhuoft/beitragezurgesch01sudhuoft.pdf

Werlin, J. “Ein unbekanntes Aderlaßbüchlein aus dem frühen 16. Jahrhundert,” Medizinische Monatsschrift 15 (1961), pp. 762-766.

Online Resources

Gerhard Eis (Wikipedia):

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerhard_Eis

“Asanger Aderlaßbüchlein,“ Handschriftencensus (describing this manuscript)

https://www.handschriftencensus.de/werke/3559

https://handschriftencensus.de/15943

“Aderlass” https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aderlass

TM 1361