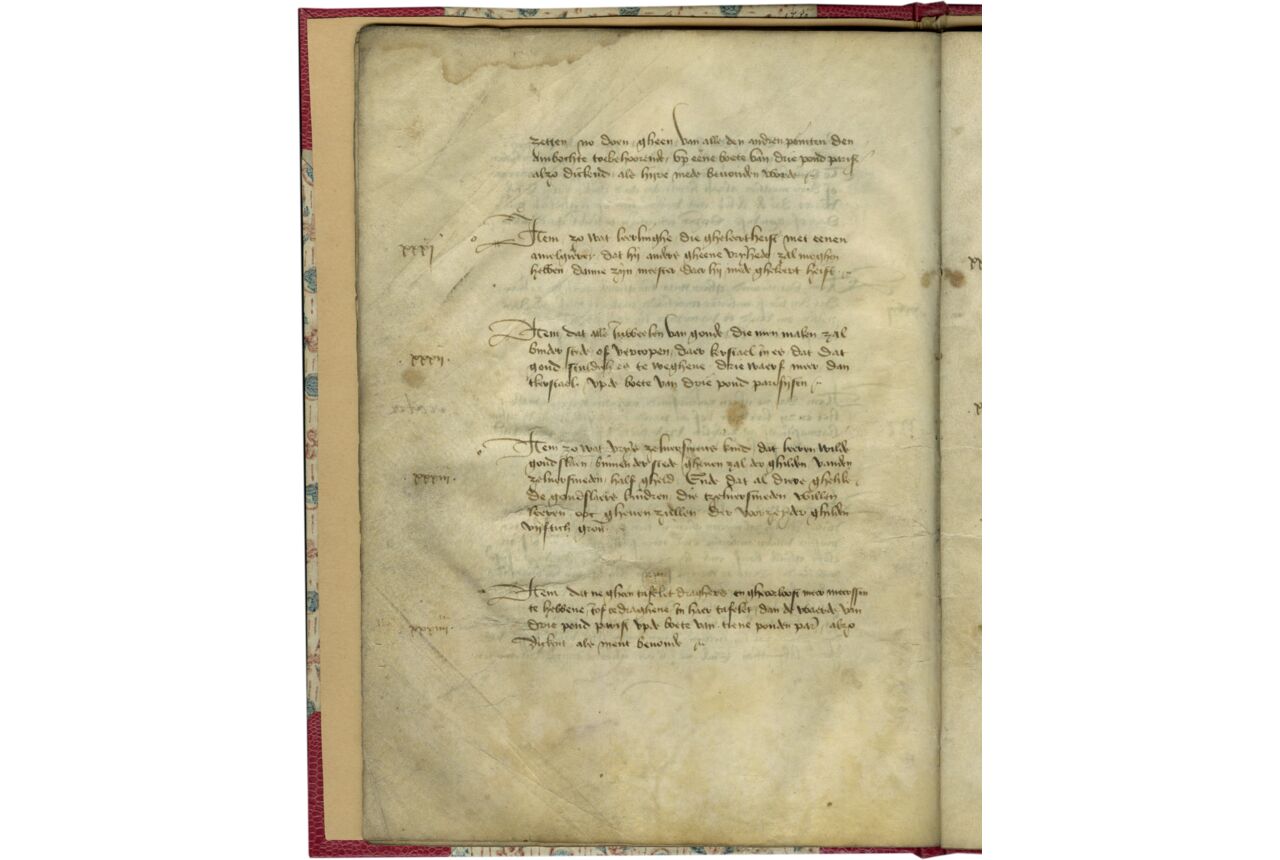

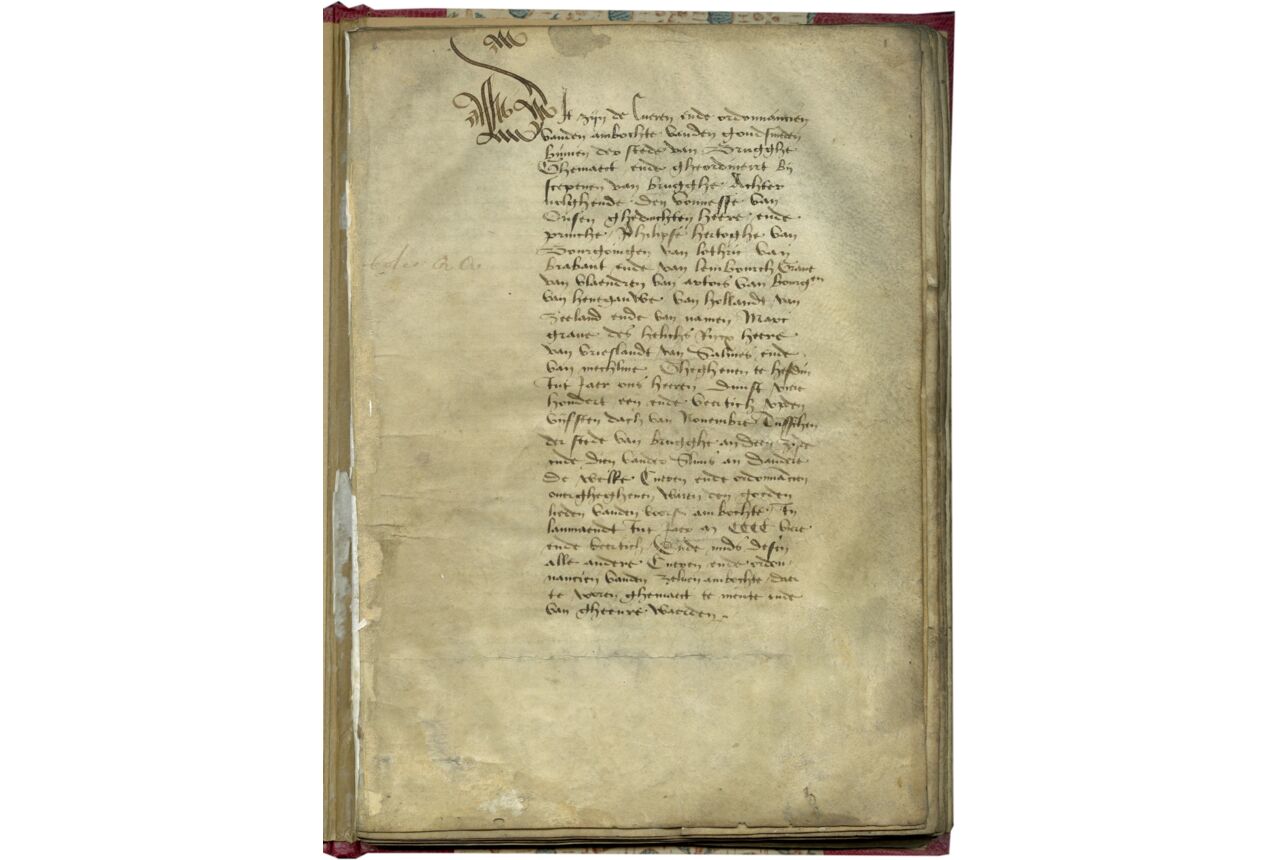

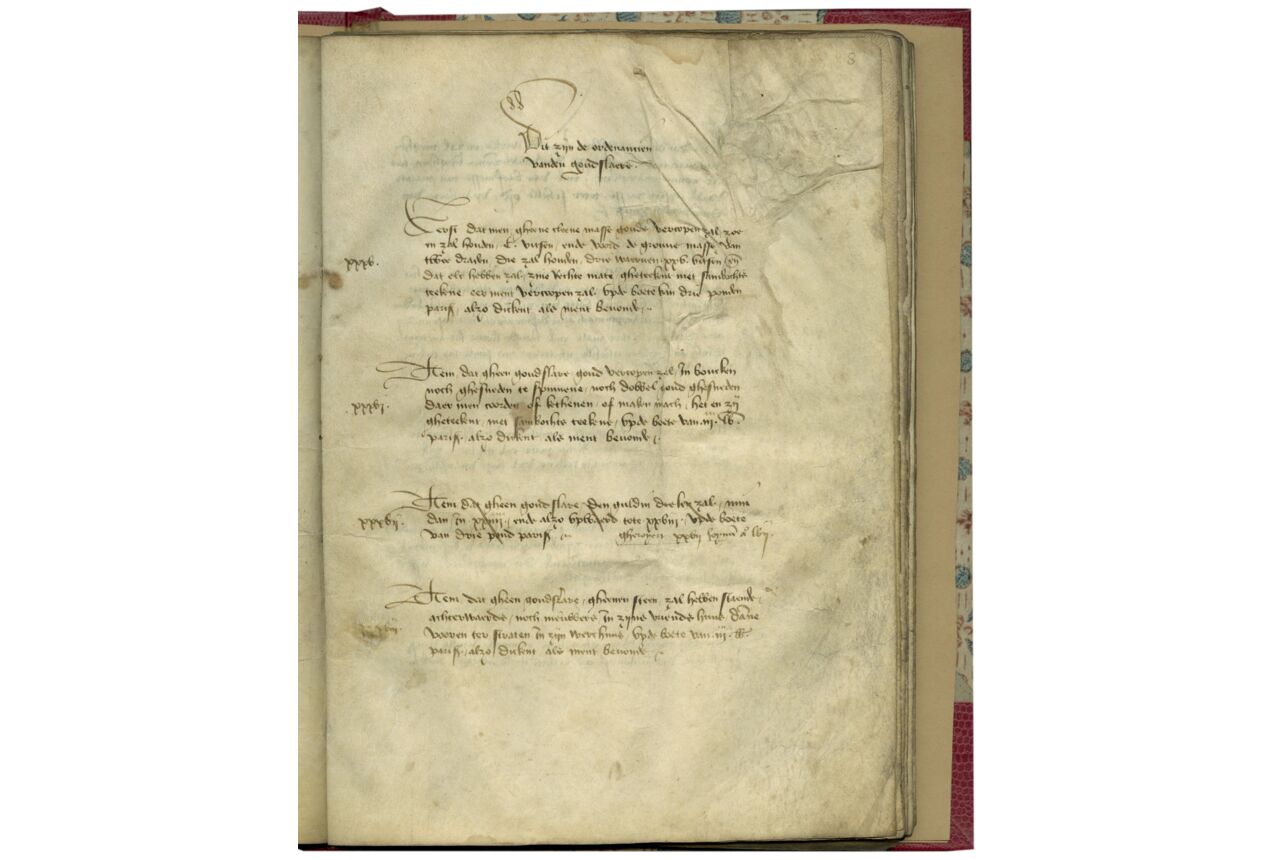

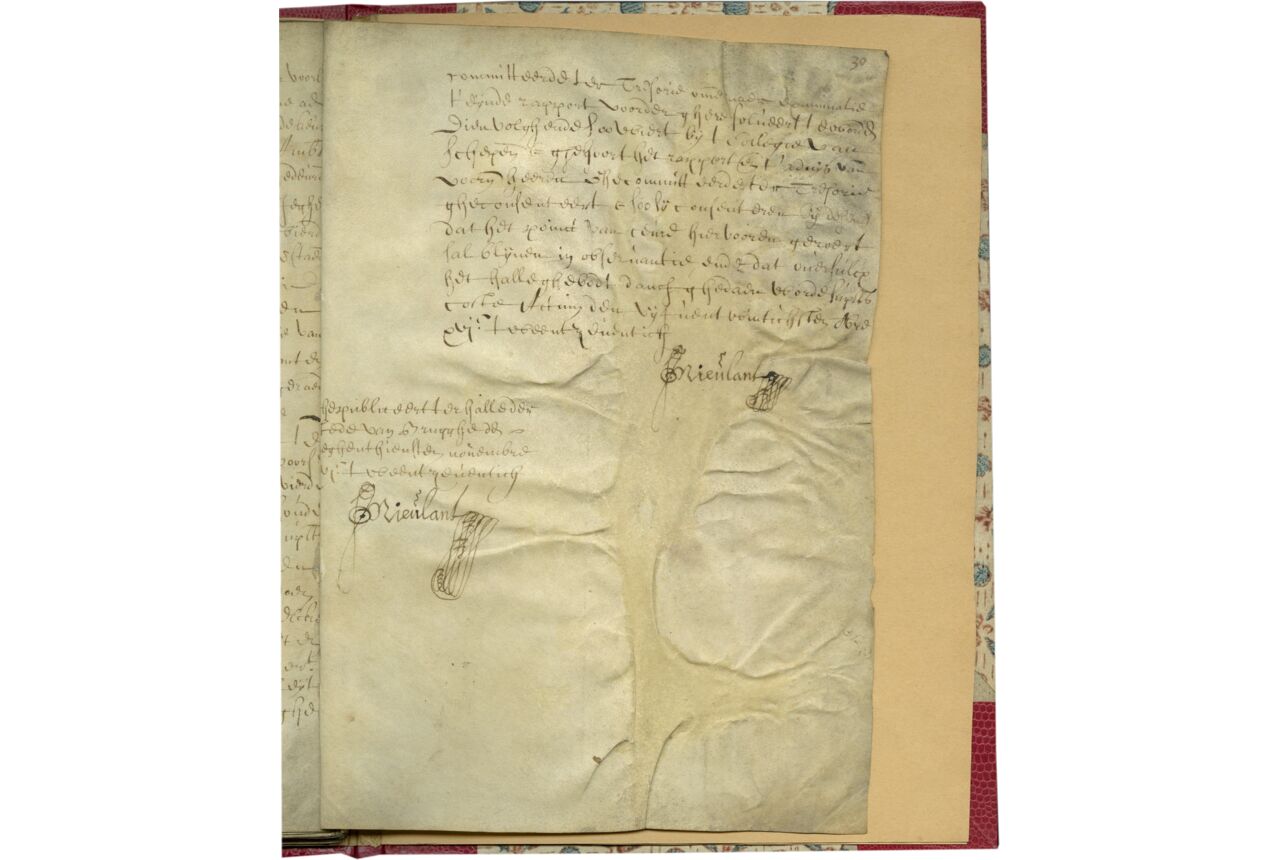

i (modern paper) + 30 + (modern paper) folios on parchment, modern foliation in Arabic numerals in faint brown ink, 1-30 (collation i18 i8 [+9 through 12; ff. 27-30, structure uncertain]), ff. 1-18v ruled very faintly in crayon with horizontal and vertical bounding lines, prickings visible in the upper, outer, and lower margins (justification 185-192 x 115-118 mm.), written in a well-formed Gothic cursive script in thirty-three long lines, ff. 19-30v ruled with full-length vertical bounding lines, apparently produced by folding the leaves lengthwise into quarters (justification 191-228 x 140-150 mm.), written in a series of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cursive hands in twenty-three to thirty-one long lines, three-line calligraphic initial on f. 1, some underlining and annotating of the initial 1441 ordinances, some soiling and rubbing, particularly noticeable between ff. 1v-4v, where some text has become nearly or completely illegible, cropping and pasting in of ff. 27-30 also contribute to slight textual losses, otherwise in good condition. Loose, with sewing intact, within modern binding of quarter red leather-like paper, with white papers decorated in light blue and red, over pasteboard, with a flat spine. Dimensions 284-290 x 202-207 mm.

Bruges was a flourishing artistic center at the end of the Middle Ages, and the creations of the city’s gold- and silversmiths rivalled those of its painters. This manuscript includes a complete copy of their first written charter issued in 1441, together with unpublished ordinances and other records from the guild up until 1479. It offers insight into the shifting regulations and fortunes of this guild, and more broadly, evidence that is relevant to economic history and the history of art. Skilled scribes copied this carefully prepared manuscript in an elegant cursive hand.

Provenance

1. There can be little doubt that this manuscript was copied in Bruges, given the highly local nature of its textual contents, ordinances and other records pertaining to the corporation of goldsmiths, silversmiths, and gold-beaters in Bruges, and the style of script. The earliest part of this manuscript contains ordinances and records issued between the years of 1441 and 1479. This section appears to have been copied in a single hand, though not necessarily all at the same time; it is possible that the articles of the initial charter were copied at some point in or after 1441 and that the subsequent ordinances and records were added later. The second quire is later, and includes additions in a number of different sixteenth-century hands and one seventeenth-century hand.

2. Private collection.

Text

ff. 1-13, DIt zijn de Cueren ende ordonnancien vanden ambochte vanden goudsmeden binnen der stede van Brugghe ... Int jaer ons heeren duust viert hondert een ende veertich [1441] vp den vijfsten dach van Nouembre ...; f. 1v, incipit, “De eerste ende tvvteste articlen vander vander Cueren vanden voorseyde ambochte ...”; f. 8, Dit zijn de ordenancien vanden goudslaere, incipit, “Eerst dat men gheene cleene masse gouds vercopen zal ... Maer zullen daer of wesen quite ende onghehouden. Alle de voorseyde boeten ghaende alzo zij stuldich worden van ghane. Ende alle dese voorzeyden Cueren ende ordonnancien zullen staen te minderne ende te meerzene Bij Scepenen van Brugghe”;

The 1441 charter of the corporation of artisans working with gold and silver in Bruges, containing a total of sixty-seven articles, numbered in the margins with roman numerals. Among these, the first thirty-four ordinances, numbered i-xxxiiij, pertain to Bruges gold- and silversmiths (goudsmeden and zelversmeden). These are followed by thirty-three ordinances, numbered continuously with the previous ordinances, xxxv-lxvij, pertaining to Bruges gold-beaters (goudslaers). The text of these ordinances generally follows that text provided by Muylaert (see 2012, pp. 141-150), drawn from a forthcoming edition of Rijksarchief Brugge, Fonds Ambachten, 1 in De Brugse ambachtskeuren by Jan Dumolyn and Peter Stabel. Notably, however, the term goudsmet has been substituted in some instances where Muylaert’s text employs the term zelversmet without other changes to the terms of the ordinances (see, for example Article 2 on f. 2rv).

ff. 13v-16, incipit, “Treuen ende dartichste point van deser cuere bouen verclaerst ... Int jaer M CCCC zeuene ende vichtich [1457] ...”; f. 13v, incipit, “Item dat ne gheenen goudslaghere gheoorlouen en zal den ghuldenen ...”; f. 15, incipit, “Vp den eersten dach van Septembre Int jaer M CCCC drie ende tsestich [1463] ...”; f. 15, incipit, “Voord dat gheenen merssemer ...”; f. 15v, incipit, “Vp den neghen ende tvvintichsten dach van meye Int jaer M CCCC tvvee ende testich [1462] ... vanden ghoudsmeden in brugghe”;

Ten ordinances, numbered continuously with the previous sixty-seven ordinances, lxviij-lxxvij, pertaining to Bruges goldsmiths and gold-beaters and to trade. These are interspersed with records pertaining to the town council for the years 1457, 1462, and 1463. Since these are not always added in chronological order, they were probably not copied immediately following the events in question. These are not included in Muylaert’s text.

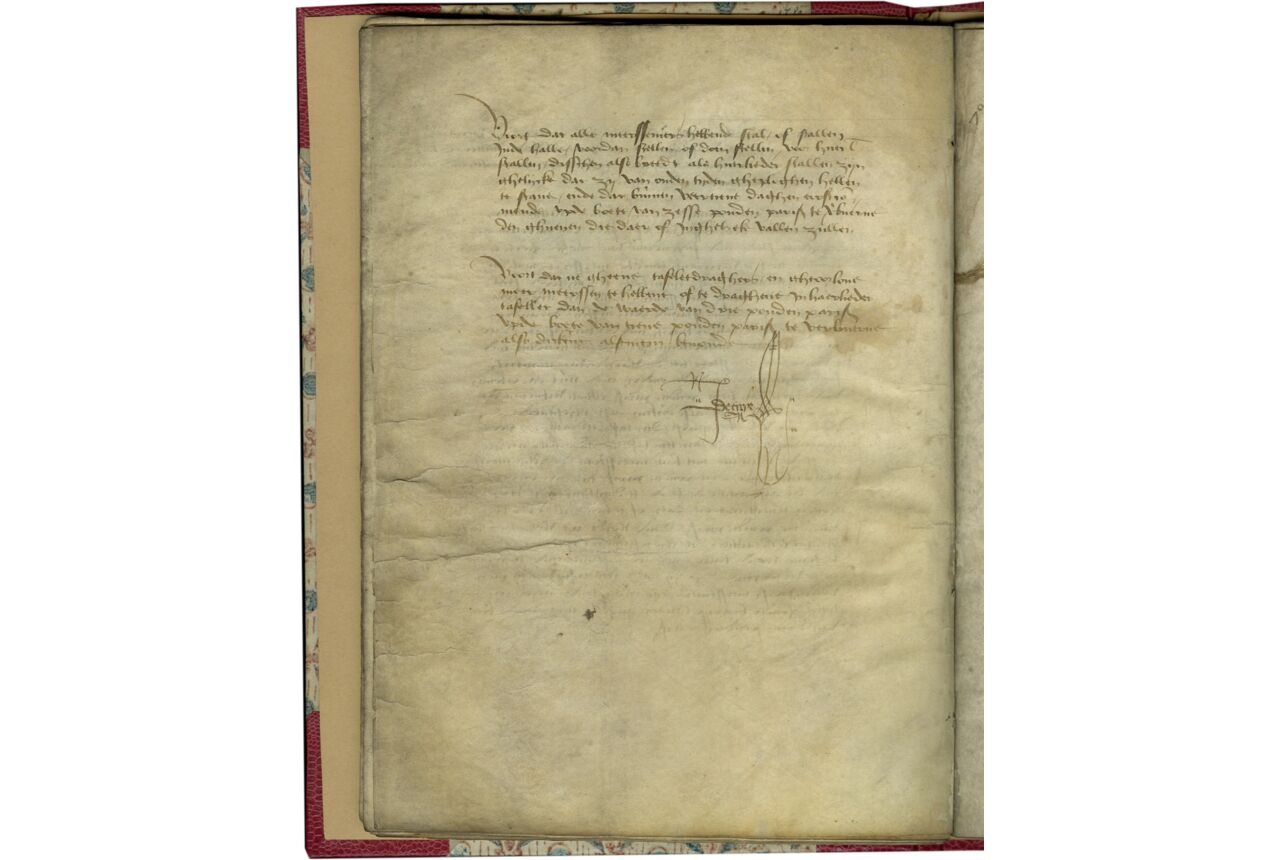

ff. 16v-18v, incipit, “Vp ten vierden dach van hoymaend Int jaer M CCCC viere ende tsestich [1464] ...”; f. 18, Vp den ellenensten dach van maerte Int jaer M CCCC neghti[...?] ende tesuentich [1479] ..., incipit, “Item dar voordamit miniende en gheoorlene ... verbuerne also dickent als ment beuonde”;

Additional records, dating specifically to 1464 and 1479, and regulations pertaining to Bruges goldsmiths and gold-beaters and to the trade in metalwork. Though they have been copied by the same hand responsible for the foregoing text, these additions have not been numbered. They do not appear in Muylaert.

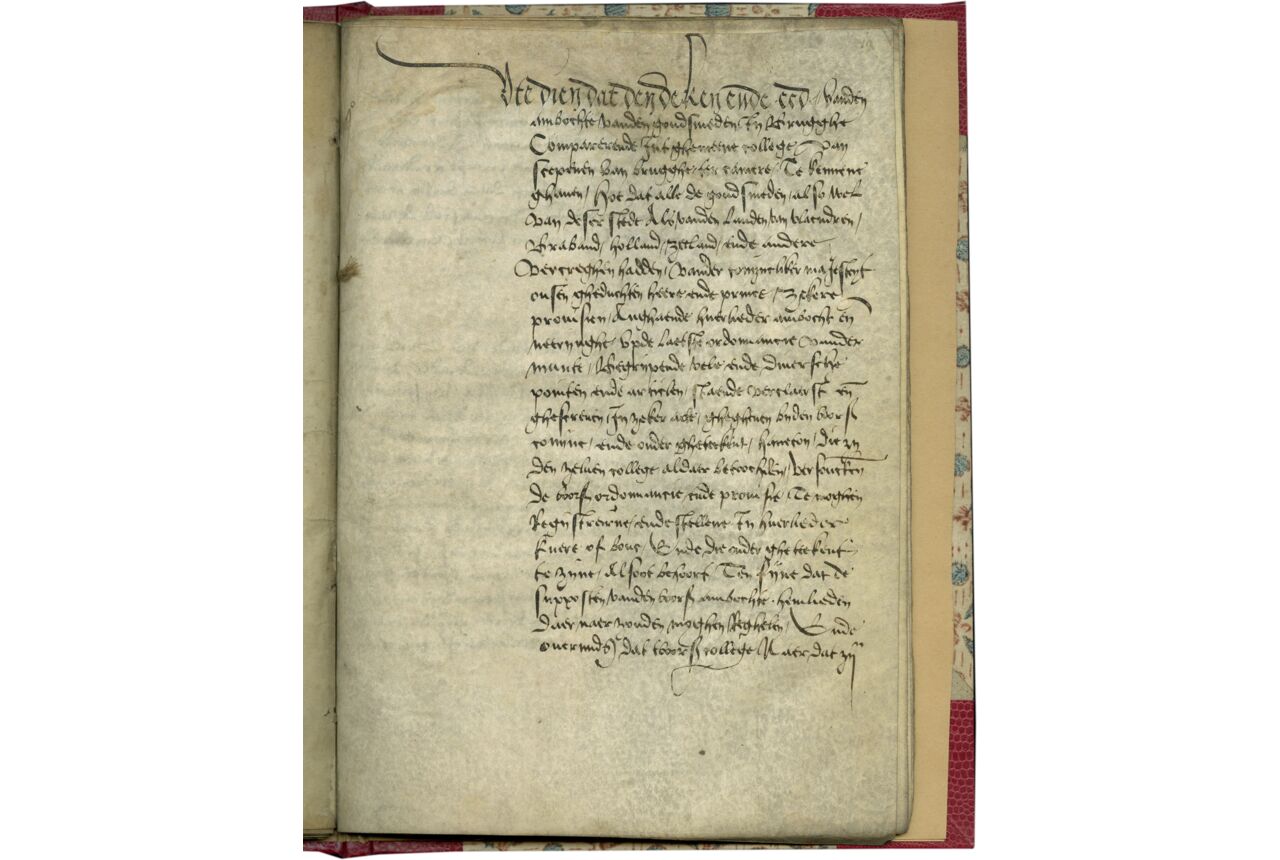

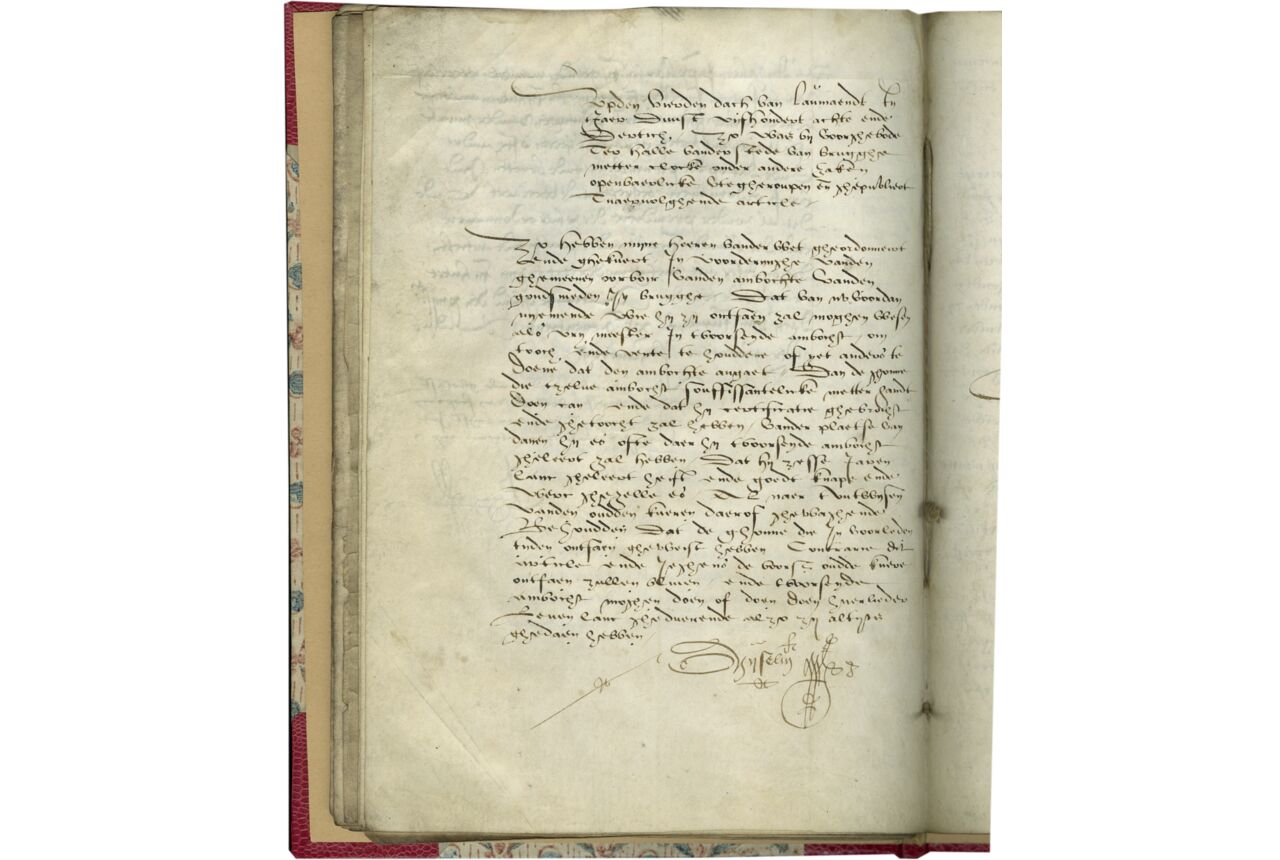

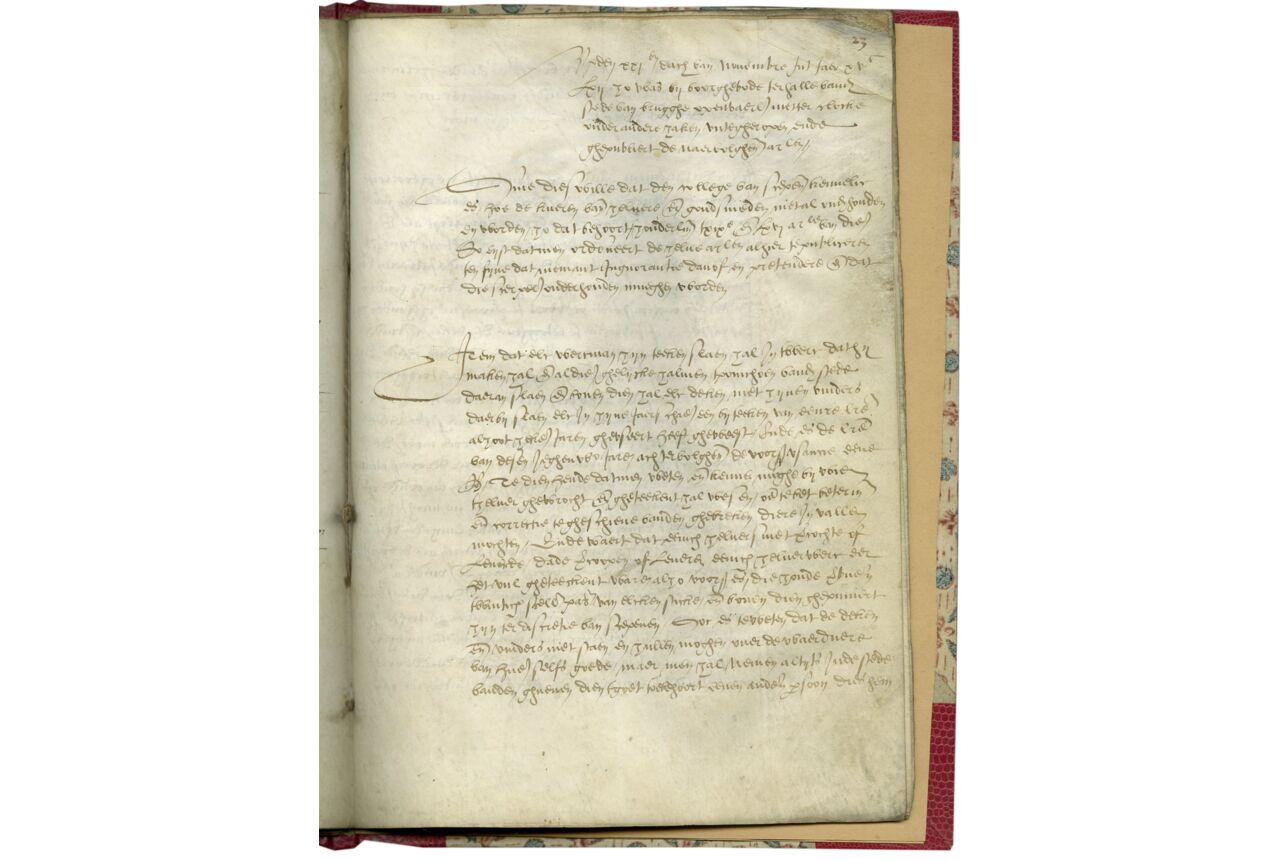

ff. 19-30, Ute dien dat den deken ende eed van den ambochte van den goudsmeden In Brugghe ... Actum teghend den xiiijen dach van junio anno xvc zeuentiene [1517] Aldus ondergheteckent. Hauetoy[?]. Aldus gheordonneerd ende ghelost Byden voors College van scepenen Vp den xviijen dach van ougst Int jaer xve[?] ende zeuentiene my put[?]”; f. 22v, Vp den vierden dach van lanmaendt In jaer duust viifhondert achte ende dertich [1538] ..., incipit, “Zv hebben myne heeren van den vvet gheordonneirt ende ghekuert ...”; f. 23, Vp den xxjen dach van Nouembre Int jaer xvc lxij [1562] zo vvas bij voorghebode ..., incipit, “Omme[?] dies vville dar den college van scepenen ...”; f. 28, incipit, “Vp de Requeste in myn heeren ...”; f. 29, incipit, “Op het vertooch by requeste Aen College van Schepenen der stede van Brugghe ... veintichste Nouembre[?] xvjc tvve[?] ent zeuentich [1672?]”; [f. 30v, blank].

Sixteenth-century additions in several hands, followed by a single seventeenth-century addition.

This manuscript contains the 1441 charter of the Bruges gold- and silversmiths, to which later ordinances and records, dating from the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries, have been added. Organized in some kind of corporate group at least as early as 1302, the goldsmiths had a long history working in the city and are mentioned in city accounts going back to the late thirteenth century. Members of corporations like that of the gold- and silversmiths were often involved in civic matters, as aldermen or on the city council, and they, in turn, were subject to that council’s ordinances. In fact, the 1441 charter was imposed upon the corporation by the city council, though the corporation most likely had some say in its terms and was later able to request emendations (see Muylaert, 2012, p. 37). The charter of 1441 appears to have been the first written charter issued for the corporation of gold- and silversmiths.

Though it is possible the first part of this manuscript was copied for the individual use of a member of the corporation of Bruges gold- and silversmiths, the inclusion of many additions in the later portion of the volume suggests that it eventually became part of the corporation’s archives, and it may even have been produced for inclusion in these archives. Relatively few documents survive from the corporation’s archives; many were dispersed into private hands when guilds were abolished under French rule at the end of the eighteenth century and some later resurfaced in public repositories during the nineteenth century. Materials from the archives of the gold- and silversmiths now survive chiefly in the municipal and state archives of Bruges. A copy of the 1441 charter of the corporation of Bruges goldsmiths and silversmiths survives in Rijksarchief Brugge, Fonds Ambachten, 1 (full transcription in Muylaert, 2012). Comparison between the text of that copy and the present manuscript reveal textual variations that warrant further study, as do the substantial continuations in the present manuscript, which are valuable sources for the history of the evolving gold and silver trade in Bruges and its regulation in the late Middle Ages and beyond.

The charter lays out the regulations for gold- and silversmiths working in Bruges in a series of sixty-seven articles specifying, among other things, rules pertaining to apprentices, journeymen, and gold-beaters (as opposed to gold- or silversmiths), and eligibility to belong to the corporation and to sell gold and silver works. The charter also addresses the maintenance and supervision of the high quality of the materials with which smiths worked, particularly the gold and silver. Article 18, for example, stipulates that gold work must meet the “touche van parijs [touch, or assay, of Paris]” which is to say it must be at least nineteen carats pure (f. 4v). Article 22, which contains underlining added at the time of its copying or at some later date, stipulates the manner in which quality was regulated, and states that three wardens were to be appointed by the guild every year to inspect and approve the gold and silver (ff. 5v-6). The charter makes provisions elsewhere for regulating the quality of the gems the gold- and silversmiths used in jewelry and other wares.

Bruges was a flourishing artistic center at the end of the Middle Ages, and the creations of the city’s gold- and silversmiths rivalled those of its painters as skilled and sought-after artistic productions. Though comparatively little Flemish metalwork of the period survives, Flemish paintings of the period bear witness to contemporary metalwork and its avid consumption, as in the case of Petrus Christus’s well-known Goldsmith in His Shop (1449), possibly a portrait of St. Eligius, patron saint of goldsmiths, made for the Bruges corporation for the occasion of the re-consecration of the smiths’ chapel to St. Eligius in 1449. The rings, vessels, and other metal objects displayed so vividly in this painting celebrate the range of wares produced by the corporation’s members for both secular and ecclesiastical buyers. Records from the fifteenth century provide a sense of the range of works produced by gold- and silversmiths, including not only rings, drinking vessels and other gold and silverware, coins, and seals, but also portrait figurines and busts, ornate jeweled or enameled reliquaries, and the elaborately worked gold chains worn by members of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

The time period covered in this manuscript traces a rise and fall in the fortunes of Flemish gold- and silversmiths. The fifteenth century saw a rising demand in Flanders for luxury goods in precious metals, driven in particular by the Burgundian court, which commissioned rich artworks for its own use and as gifts. At the same time, as a major center of European trade, Bruges metalwork was a valued commodity in a larger market. Bruges goldsmiths did not fare so well in the sixteenth century, by which point Antwerp had eclipsed Bruges as a trading center and economic and political crises drove requisitions of gold and silver. The later additions to this manuscript warrant closer study in light of the shifting fortunes of Bruges gold- and silversmiths in this later period.

Literature

Brown, Andrew. Civic Ceremony and Religion in Medieval Bruges c. 1300-1520, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

“Bruges,” The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture, ed. Colum Hourihane, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 442-445.

Dumolyn, Jan. “De Brugse ambachtsbesturen tijdens de late middeleeuwen: enkele institutionele en rechtshistorische aspecten,” Handelingen van het Genootschap voor Geschiedenis gesticht onder de henaming Société démulation te Brugge 147 (2010), pp. 309-327.

Martens, Maximiliaan Pieter Jan. “Artistic Patronage in Bruges Institutions, ca. 1440-1482,” PhD diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 1992.

Muylaert, Silke. “De Brugse goud- en zilversmeden in de late middeleeuwen: een prosopografische studie,” MA thesis, Universiteit Gent, 2012, vol. 1.

Ogden, Jack. “The Technology of Medieval Jewelry,” Ancient & Historic Metals: Conservation and Scientific Research: Proceedings of a Symposium Organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Getty Conservation Institute, November 1991, ed. David A. Scott, Jerry Podany, and Brian B. Considine, Marina del Rey, CA, Getty Conservation Institute, 1994, pp. 153-182.

Wolff, Martha. “Petrus Christus,” Fifteenth- to Eighteenth-Century European Paintings in the Robert Lehman Collection: France, Central Europe, the Netherlands, Spain, and Great Britain, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, pp. 62-73.

Online Resources

Petrus Christus, A Goldsmith in his Shop (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection)

http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/459052

TM 831