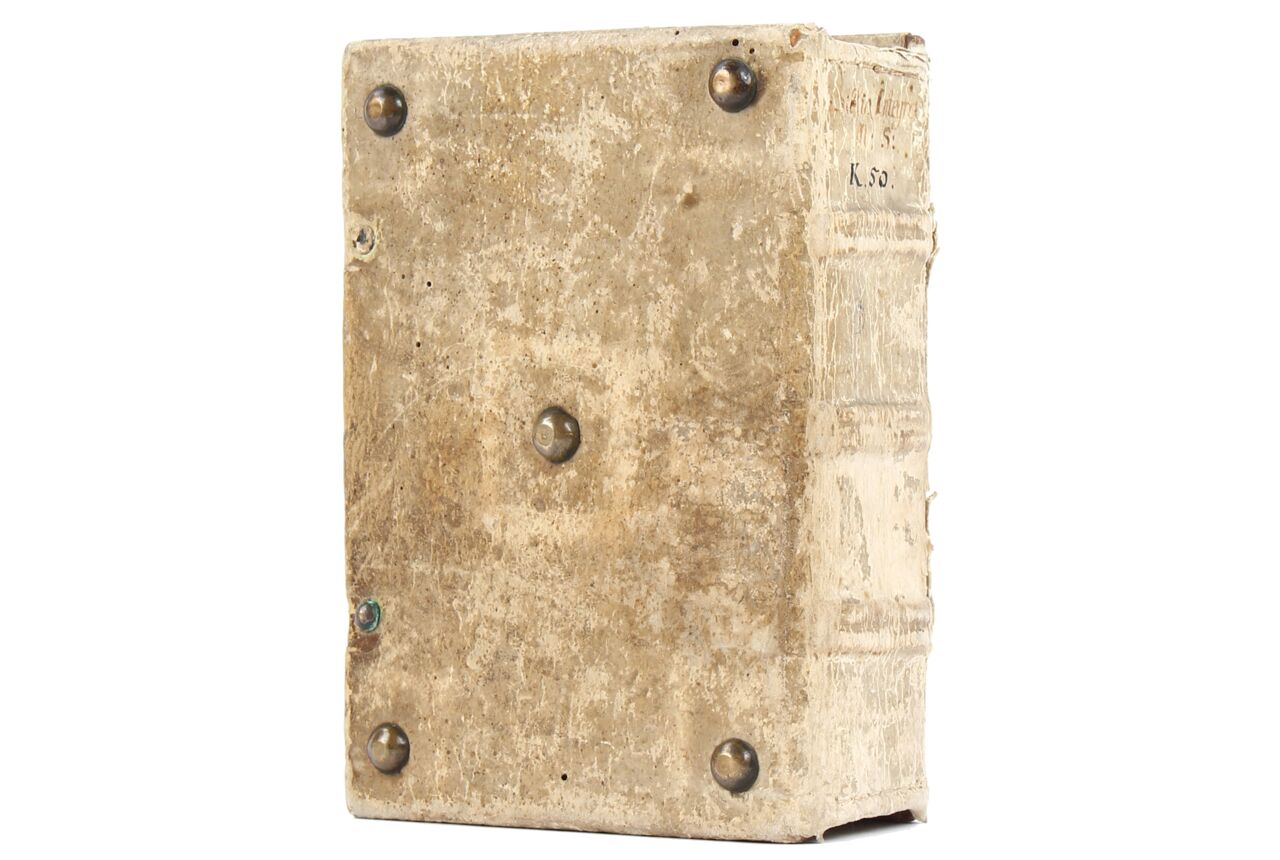

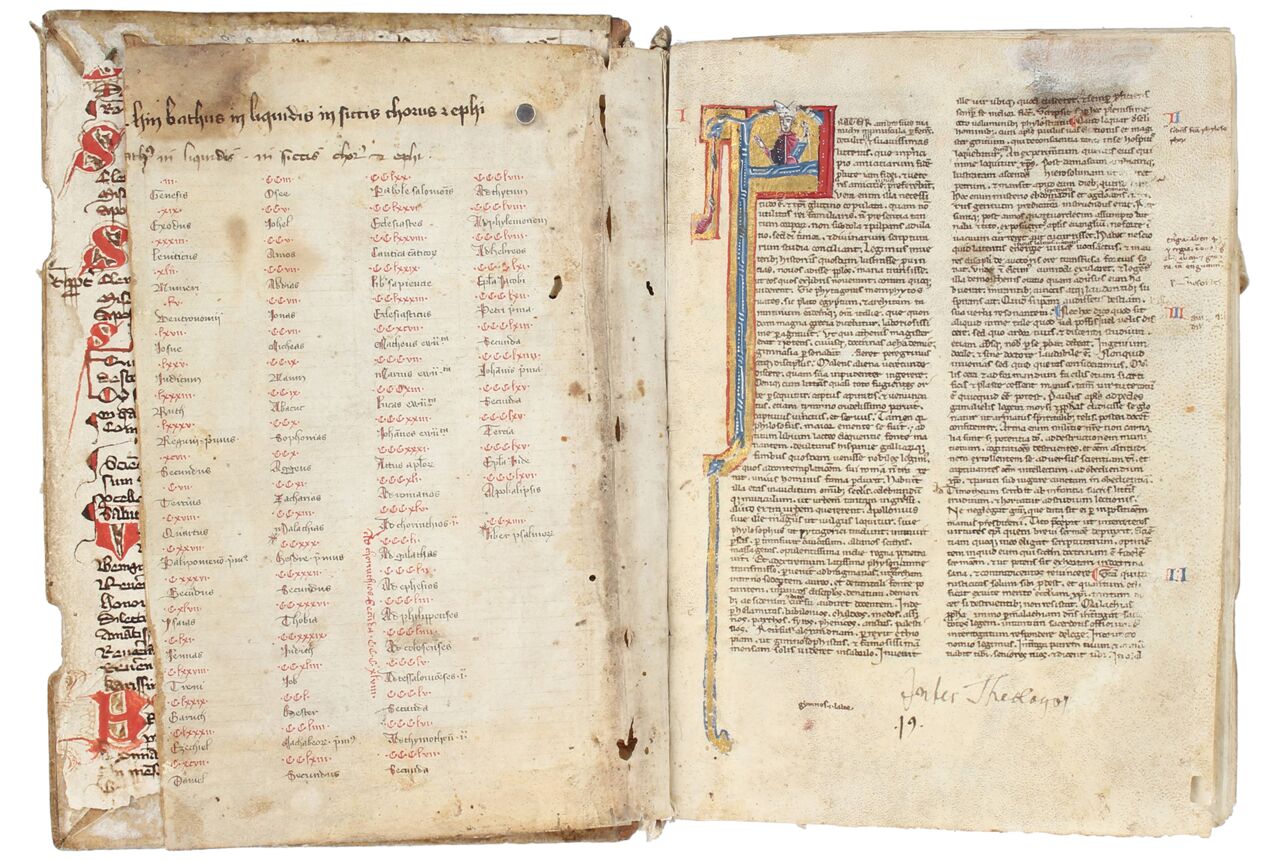

389 folios on parchment, medieval foliation in very small red Roman numerals upper margin on the verso, with f. 295 followed by 297, and with f. 332bis: i-ccxcv, *ccxvii-cccxxxii, cccxxxii bis-ccclxxi (not including ff. 371-389), complete (collation i-xxii12 xxiii6 [6, f. 270v, blank] xxiv12 xxv12+1 [f. 295 added after 12] xxvi-xxviii12 xxix10 [10, f. 341rv, blank] xxx-xxxi12 xxxii6 xxxiii12 xxxiv6), horizontal catchwords at the end of most quires (some trimmed), quires 1-26 are signed at the begining in early arabic numerals, ruled in lightly in lead, triple rules between the columns, and with an extra set of double bounding lines in outer margin, visible on some folios, (justification 135-130 x 100-90 mm.), copied in a very tiny, regular southern gothic bookhand in two columns of 53-54 lines, Interpretation of Hebrew Names and Biblical lexicon copied in very small scripts in three columns, red rubrics, running titles and chapter numbers in red and blue, one-line red or blue initials, two-line red or blue initials, often with pen decoration in the opposite color (style of pen decoration varies throughout the volume), 2-line gold initials on blue or red grounds, approximately SIXTY DECORATED or ILLUMINATED INITIALS in two general styles, the first, with colored vine scrolls on gold grounds, some with other motifs including diaperwork, and from f. 197 to end, skillful violet or orange initials, 9- to 6-lines, infilled with bold acanthus leaves or other motifs in light green, orange, on blue grounds, edged in red (discussed below), FOURTEEN small historiated initials, TWENTY-FOUR LARGE HISTORIATED INITIALS BY SEVERAL ARTISTS (see below), ONE MARGINAL MINIATURE of a kneeling supplicant figure, tonsured and in burgundy robes (accompanying the opening of Deuteronomy), front flyleaf and the first six folios with a water stain at the upper right, the margins of these leaves are somewhat damaged, f. 3, torn, some small scuffs and spots, trimmed at edges removing parts of some catchwords in places, slight flaking to ink and paint in some places, bottom margin f. 371 cut away, overall in excellent condition. EARLY GERMAN BINDING, fifteenth- or sixteenth-century, of light colored leather over sturdy wooden boards, outer edge of the upper board slightly beveled, boards extend slightly beyond the book block, spine with three raised bands, with “Biblia Integra / M:S:” and “K 50” in pen (both probably eighteenth-century), five brass bosses on each board, two leather strap and pin fasteners, fastening back to front, unobtrusive modern repairs to the spine, slight split at the top of the spine. Dimensions 192 x 135 mm.

Italian examples of portable or “pocket” Bibles are less common than their Parisan counterparts. This early Italian example of the innovative new format is textually and physically distinct from contemporary French Bibles. Non-biblical texts including a treatise on preaching and an alphabetical lexicon shed light on its use. In the fifteenth century it was purchased in Italy by a Carthusian monk, who brought it home to Germany, and it is still preserved in its fifteenth century German binding, with evidence of liturgical use by the Carthusians. This is a delightful manuscript with varied and inventive illumination by several artists including one with some relationship to the “miniatore di Lanfranco de Pancis.”

Provenance

1. Written and illuminated in northern Italy, most likely in Pauda, in the mid-thirteenth century, as suggested by the evidence of the script and the style of the decoration; the penitent depicted kneeling in supplication below the opening of Deuteronomy might be a Franciscan, suggesting early Franciscan ownership, although the evidence is unclear (his robes here are burgundy-red as opposed to the more usual brown, but his tonsured head and corded belt might indicate his Order). Details of the text, and in particular the inclusion of summaries of books of the Bible known as capitula lists are evidence that this was copied from an exemplar dating from the early thirteenth century at the latest.

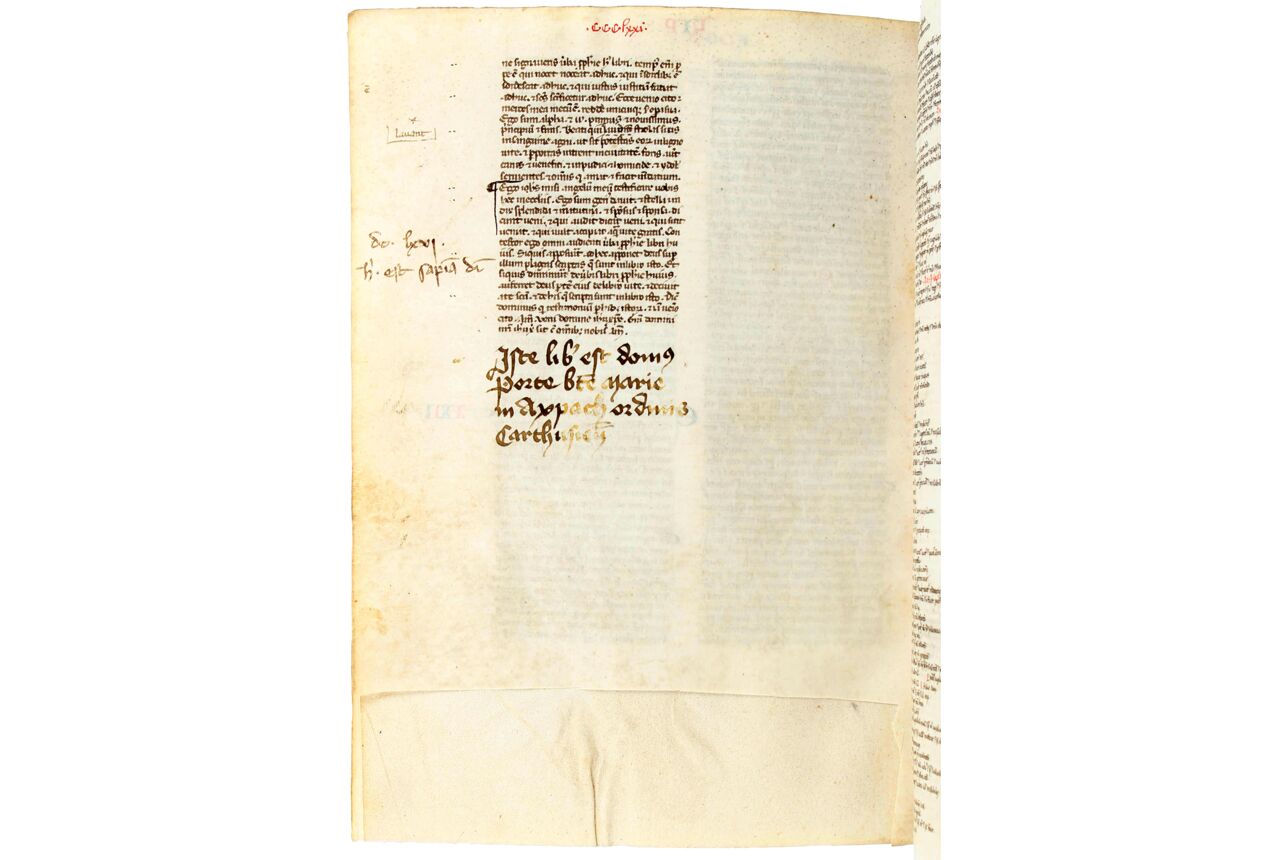

2. Belonged to the Carthusian Charterhouse of Aggsbach in the fifteenth century. It was purchased in Italy by Prior Johannes as recorded in his inscription f. 296: “Iste liber est domus porte beate Marie in axpach ordinis carthusiensis. Et est emptus per dominum Johannem priorem a quodam sacerdote In ytalia”; the manuscript remained at Aggsbach through the fifteenth century; with the ex libris of Aggsbach repeated in another hand on f. 331, “Iste liber est domus porte beate Marie Virginis in Axpach Ordinis carthusiensis,“ and on f. 371v at the end of the text.

The Charterhouse of Aggsbach, near Melk in Lower Austria (founded in 1380) was dissolved in 1782 as part of the reforms of Emperor Joseph II, and its library passed mostly to the Hofbibliothek of Vienna (later incorporated into the ÖNB) with small numbers of volumes passing to other libraries and into private hands. The current binding is very likely from Aggsbach.

3. Owned by Göttweig Abbey, diocese of St. Pölten, near Krems in Lower Austria (founded as a Benedictine house of Canons Regular in the eleventh century), possibly after 1738, since it is not recorded in the booklist from that date; it is recorded in the Abbey’s booklist from 1756 (Online Resources; it is also listed in Werl, 1843), where it was shelved as “K 50” (recorded on our manuscript’s spine).

4. German private collection since the 1950s.

Text

Front pastedown, paper leaf, with a text copied in the fifteenth century in a cursive gothic script on proper modes of address to different categories of people; presented in tablular form, with red initials;

Front flyleaf verso (recto blank), list in four columns of the biblical books contained in the manuscript with their folio numbers (added when the leaves were foliated in red roman numberals on the verso of each opening);

ff. 1-371v, Latin Bible, with prologues as follows: f. 1, [General prologue] Frater ambrosius [Stegmüller 284]; f. 3, [prologue to Genesis] Desiderii mei [Stegmüller 285]; f. 4, Genesis; f. f. 20, Exodus; f. 33v, Leviticus; f. 42v, Numbers; f. 56, Deuteronomy; f. 67v, [prologue to Joshua] Tandem finito [Stegmüller 311]; f. 68, Joshua; f. 75v, Judges; f. 83v, Ruth; f. 84v, [prologue to Kings] Viginti et duas [Stegmüller 323], f. 86, 1 Kings; f. 97v, 2 Kings; f. 107, 3 Kings; f. 118v, 4 Kings; f. 128, [prologue to Chronicles] Si septuaginta [Stegmüller 328]; f. 128, 1 Chronicles; f. 136v, 2 Chronicles; f. 147v, Isaiah; f. 161v, [prologue to Jeremiah] Hieremias propheta [Stegmüller 487]; f. 162, Jeremiah; f. 178v, Lamentations; f. 180, Baruch; f. 182, [prologue to Ezechiel] Ezechiel propheta [Stegmüller 492]; f. 182v, Ezechiel; f. 197, [prologue to Daniel] Danielem prophetam [Stegmüller 494]; f. 197v, Daniel; f. 203v, [prologue to Minor prophets] Non idem ordo est [Stegmüller 500]; f. 203v, Hosea; f. 205v, Joel; f. 206, Amos; f. 207v, Obadiah; f. 207v, Jonah; f. 208, Micah; f. 209v, Nahum f. 210, Habbakuk; f. 210v, Zephaniah; f. 211, Haggai; f. 211v, Zechariah; f. 213v, Malachi; f. 214v, [prologue to Psalms], Scio quosdam [Stegmüller 443]; f. 214v, Psalms; f. 230v, [prologue to Ezra] Utrum difficilius [Stegmüller 330]; f. 230v, 1 Ezra; f. 233, Nehemiah [Ezra 2(3) is not included, and there is a marginal note at the end of Nehemiah, noting its absence]; f. 237, [prologue to Tobit] Cromatio et heliodoro ..., Mirari non desino [Stegmüller 332]; f. 237, Tobit; f. 239v, [prologue to Judith] Apud hebreos [Stegmüller 335]; f. 240, Judith; f. 243v, [prologue to Job] Cogor per singulos [Stegmüller 344]; f. 244, Job; f. 251, [prologue to Esther] Librum hester; Rursum in libro [Stegmüller 341 and 343, copied as one prologue]; f. 251, Esther; f. 254v, [prologue] Machabeorum librum duo [Stegmüller 551]; f. 254v, 1 Maccabees; f. 263, 2 Maccabees, ending f. 270; [f. 270, col. b, added in a very tiny script by an Italian scribe, probably contemporary with the Bible, brief ars praedicandi, “Octo sunt modi dilitandi sermones. Primus est ponendo orationem pro nomine sicut fit in diffinicionibus de scriptionibus interpretationibus ...”; f. 270v, blank]; f. 271, [prologue to Proverbs] Iungat epistola [Stegmüller 457]; f. 271, Proverbs; f. 276v, Ecclesiastes; f. 278v, Song of Songs; f. 279v, Wisdom; f. 284, [biblical introduction to Ecclesiasticus, copied as a prologue], Multorum nobis; f. 284, Ecclesiasticus, with the Prayer of Solomon, ending f. 295v, mid col. b, remainder blank]; f. 297, [prologue to Matthew] Matheus ex iudea [Stegmüller 590]; f. 297, Matthew; f. 306v, [prologue to Mark] Marcus evangelista [Stegmüller 607]; f. 307, Mark; f. 313, [prologue to Luke] Lucas syrus natione [Stegmüller 620]; f. 313v, Luke; f. 323v, [prologue to John] Hic est Iohannes [Stegmüller 624] ; f. 323v, John; f. 331v, [prologue to Acts] Lucas anthiocenses natione syrus [Stegmüller 640]; f. 331v, Acts, concluding f. 340v; f. 341rv, blank; f. 342, Romans; f. 345v, [prologue to 1 Corinthians] Corinthii sunt achaici [Stegmüller 685]; f. 345v, 1 Corinthians; f. 349, [prologue to 2 Corinthians] Post actam [Stegmüller 699]; f. 349, 2 Corinthians; f. 351v, [prologue to Galatians, copied at the end of 2 Corinthians with no rubric] Galathe sunt greci [Stegmüller 707]; f. 351v, Galatians; f. 352v, [prologue to Ephesians] Ephesii sunt asyani [Stegmüller 715]; f. 352v, Ephesians; f. 353v, [prologue to Philippians] Philippenses sunt macedones [Stegmüller 728]; f. 353v, Philippians; f. 354v, [prologue to Colossians] Colosenses et hii [Stegmüller 736]; f. 354v, Colossians; f. 355v, [prologue to 1 Thessalonians] Thessalonicenses sunt macedones [Stegmüller 747]; f. 355v, 1 Thessalonians; f. 356, [prologue to 2 Thessalonians] Ad thessalonicenses [Stegmüller 752]; f. 356, 2 Thessalonians; f. 356v, [prologue to 1 Timothy] Tymotheum instruit [Stegmüller 765]; f. 356v, 1 Timothy; f. 357v, [prologue to 2 Timothy] Item Tymotheo scribit [Stegmüller 772]; f. 357v, 2 Timothy; f. 358, [prologue to Titus] Tytum commonefacit [Stegmüller 780]; f. 358, Titus; f. 358v, [prologue to Philemon] Phylemoni familiares [Stegmüller 783]; f. 358v, Philemon; f. 359 , [prologue to Hebrews] In primis dicendum [Stegmüller 793] ; f. 359, Hebrews [lacks painted initial]; f. 361v, [prologue to James], Iacobus apostolus [Stegmüller 806]; f. 361v, James; f. 362v, [prologue 1 Peter], Symon Petrus [Stegmüller 815 or 816, shortened]; f. 362v, 1 Peter; f. 363v, [prologue 2 Peter], Per fidem [Stegmüller 818]; f. 363v, 2 Peter; f. 364v, [prologue 1 John], Rationem verbi [Stegmüller 822]; f. 364v, 1 John; f. 365v, [prologue 2 John], Usque a deo [Stegmüller 823]; f. 365v, 2 John; f. 366, [prologue 3 John], Gaium pietatis [Stegmüller 824]; f. 366, 3 John; f. 366, [prologue Jude], Iudas apostolus [Stegmüller 825]; f. 366, Jude; f. 366v, [prologues to Apocalypse], Iohannes apostolus; Apocalipsis iohannis [Stegmüller 834 and 829]; f. 366v, Apocalypse, ending f. 371v.

Capitula lists are found before the following books (identified by their sigla in De Bruyne, 1914 [abbreviated De Br]): f. 3v, [Genesis], De lucis exordio [De Br, Is]; f. 19v, [Exodus], De rege qui opprimebat [De Br, Is]; f. 32v, [Leviticus], Locutus est dominus [De Br, A]; f. 42, [Numbers], Recognitio duodecim [De Br, A]; f. 55, [Deuteronomy], Et tollentes ...; Accessistis ad me [De Br, A, beginning at no. 3]; f. 67v, [Joshua], Promittit deus [De Br, A]; f. 75v, [Judges], Iudas eligitur [De Br, A]; f. 85v, [1-2 Kings], ubi orat anna [De Br, Sp]; f. 106v, [3 Kings], Senectus david [De Br, A]; f. 117v, [4 Kings], Assumptio helie [De Br, A at lviiii]; f. 297, [Matthew], Nativitas christi [De Br, B]; f. 306v, [Mark], De iohanne baptista [De Br, B]; f. 313, [Luke], Zacharias angelo [De Br, B?].

The capitula lists in this Bible may be compared with those in Sitten, Archives de la chapitre, MS 15, an eleventh century “Giant Bible,” copied in Central Italy, which includes the series ‘Is’ (but for Genesis only), and ‘A’ for Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Joshua, and Judges; see also Quentin, 1922, pp. 378-380, discussing Italian Giant Bibles, and noting that a mixture of capitula lists from Alcuin’s and Spanish Bibles was characteristic of the small sample of Bibles from this large group studied by him.

ff. 372-385, incipit, “Aad apprehendens ... Zuzim consiliantes eos vel consiliatores eorum”;

The version of the Interpretations of Hebrew Names that is commonly found in Bibles dating after c. 1230; Stegmüller, 1950-1980, no. 7709; printed numerous times in the fifteenth century, and in the seventeenth century, when it was included in among the works of Bede, Cologne, 1612, 3:371-480; there is no modern edition, despite the text’s great importance for the history of the Bible, exegesis and preaching in the High Middle Ages. The text is attributed in one manuscript (Montpellier, Bibl. de la Faculté de Médecine, MS 341) to Stephen Langton (d. 1228) but this attribution is still an open question (Murano, 2010).

ff. 385-389v, [Alphabetical distinction collection], incipit, “Angelus, purus natura, reconciliator, fidolis incastodiendo, ..., Aquilo, aquas congelat unde aquilo quod est aquas lignas, frigidus est,

... xl annis fuerunt filiis israel ... in deserto”; [followed by an added list of the books of the Bible], incipit, “Hic est libri et ordo et numerous biblie. Genesis, ....”

This alphabetical list of words from the Bible followed by their figurative meanings shares the same opening entry with Stegmüller no. 8914, listing Brussels, Bibl. Royale, MS 1315 (s. xiv, from the Charterhouse of Cologne), ff. 62-73v, with a different ending; see also Oxford, Merton College, MS 206 (Online Resources), suggesting this text is also found in Vatican City, BAV, MS Reg. lat. 1637/2, Paris, BnF, MS lat. 10473, Klosterneuburg, Stiftsbibl., MS1066, and Prague, Univ. Bibl., MS 1919.

Back pastedown, incipit, “Sicut audivimus a referenti et vidimus …. potius adlator quod p//. pre//”

Leaf from a paper manuscript, reused here in our manuscript’s binding, with a letter by the Emperor Sigismund, written around 1415 after the opening of the Council of Constance, addressing the Hussite heresy. Edited Höfler, 1865; comparison of the missing words here with the edition suggests that this is the same manuscript used by him for that edition (1865, pp. 267-78, no. 5). His identification of his source as “Ex cod. Mellicensi 114” (ie. from Melk Abbey, MS 114) must be an error for Göttweig MS 114. Melk MS 114 is an unrelated Missal from Einsiedeln, but the nineteenth-century manuscript catalogue of the manuscripts of Göttweig Abbey by P. Vinzenz Werl records a later shelfmark of Göttweig MS K 50 as “114” (entered in red pencil in his inventory; Online Resources).

Illustration

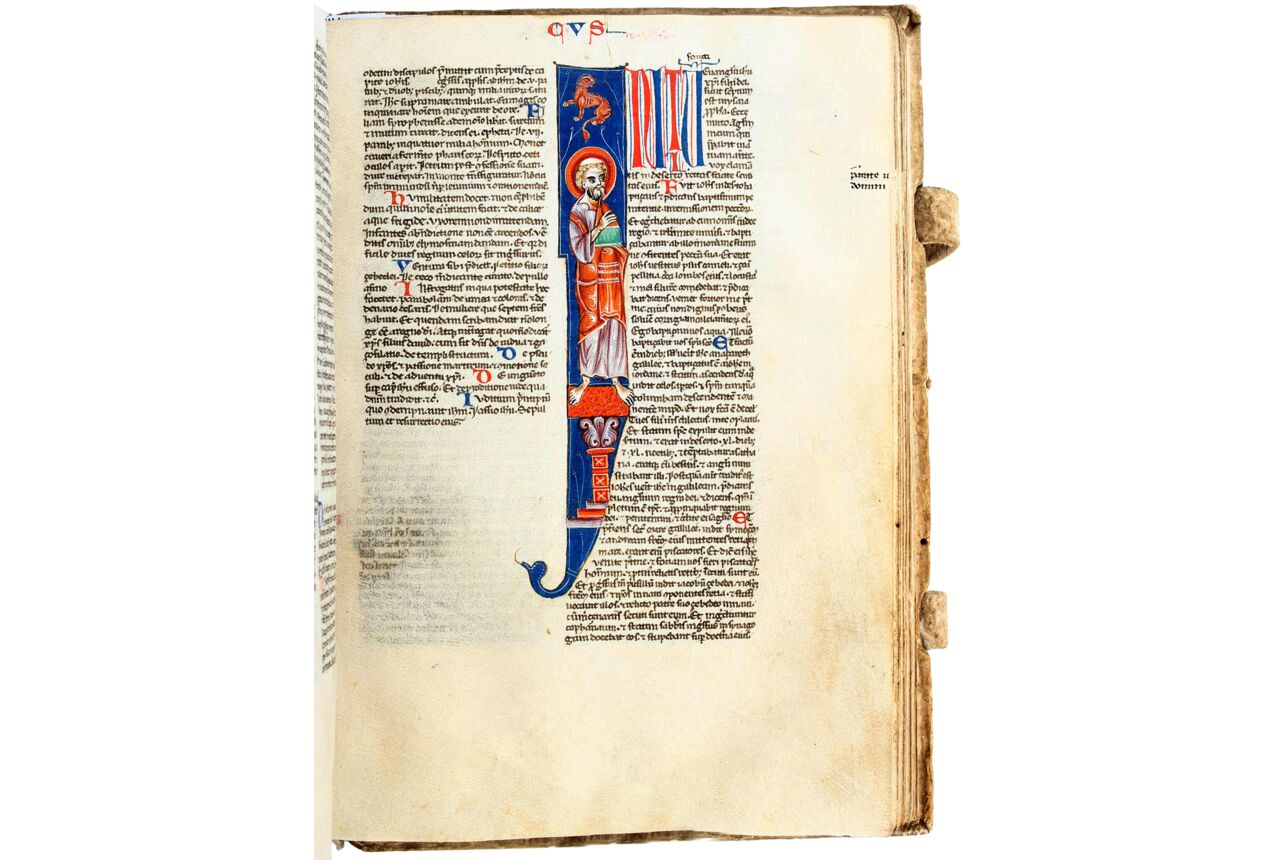

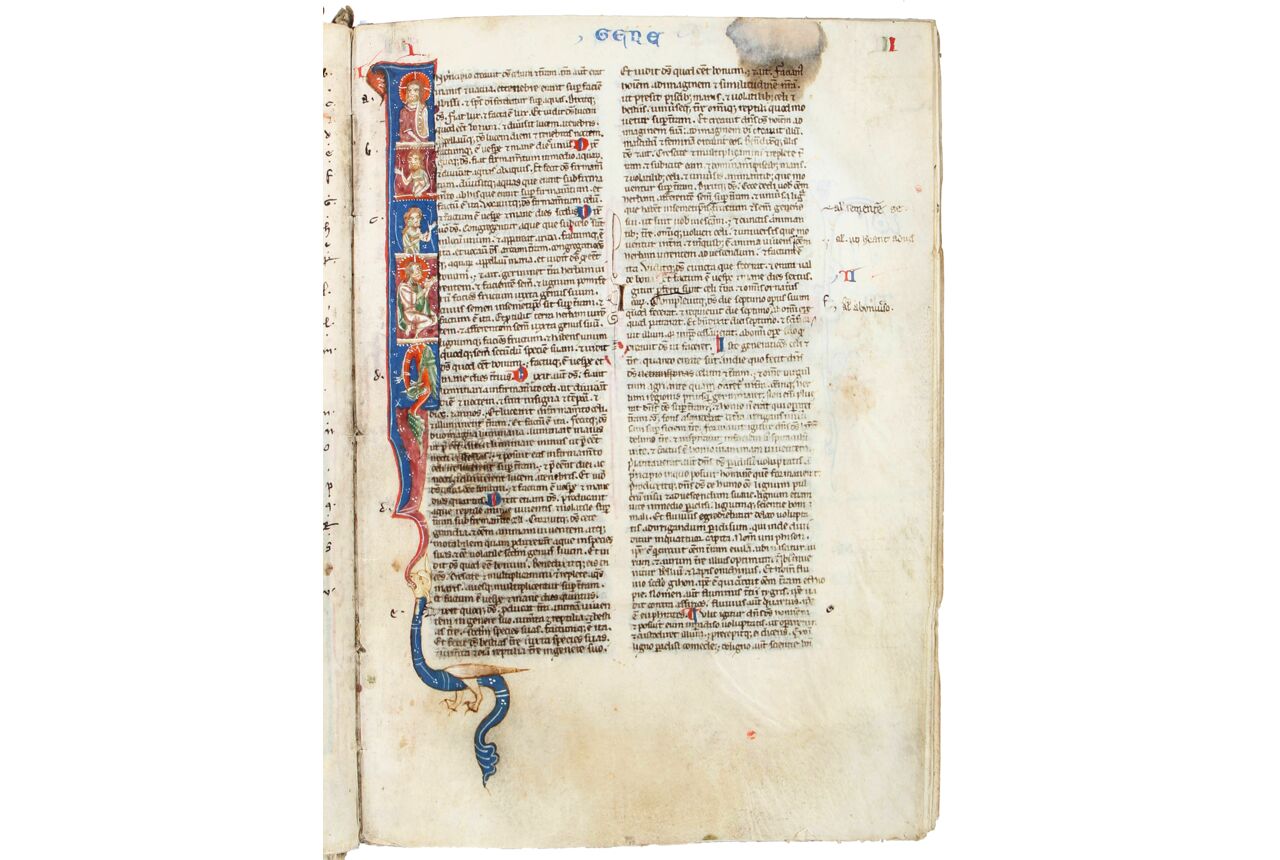

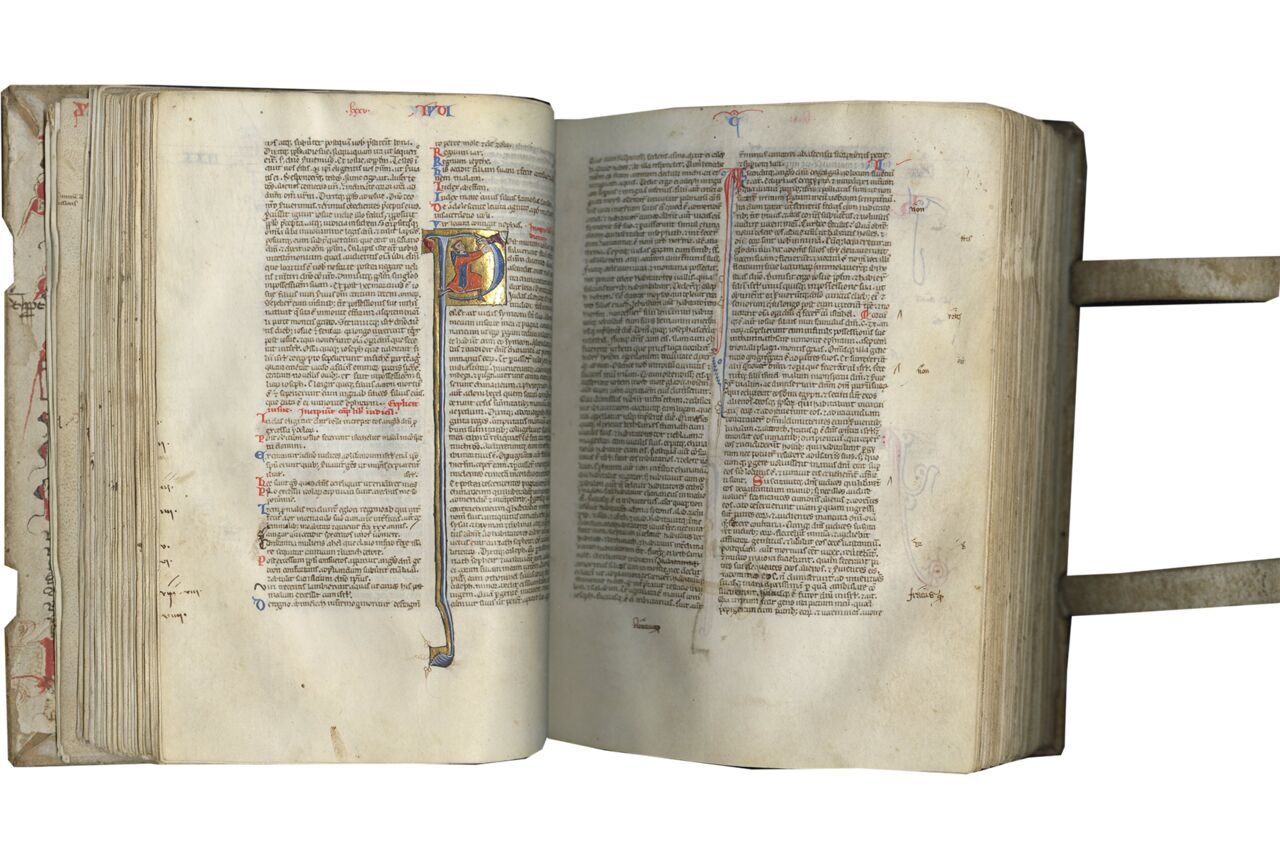

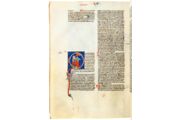

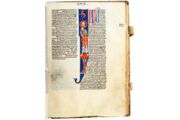

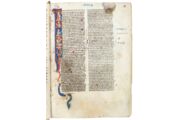

Twenty-four historiated initials, and one marginal painting. The subjects of many of the initials are unusual, including the Genesis initial, which does not depict the usual scenes of creation, and the initial to Lamentations on f. 178v that is illustrated with the Annunciation. Even more unusual for a Bible from the thirteenth century (and indeed, although to a lesser extent, for any medieval Bible), is the presence of historiated initials before prologues and even capitula lists (the norm would be to use historiated initials only the first prologue and the books of the Bible).

Subjects as follows:

f. 1, (Frater) Bishop blessing;

f. 3, (Desiderii) Scribe at a writing desk [9-line blue, on gold and infilled with gold;

f. 4, (Genesis) Extending full-length of the page, 4-compartments with Christ at the top, two figures (maybe Adam and then Eve, separately), followed by Christ in supplication and a twisted drollery dragon biting its own tail;

f. 33v, (Leviticus), Figure holding a scroll;

f. 56 (Deuteronomy), Lower margin, penitent figure, kneeling, in a dark red robe;

f. 75v, (Judges), Prophet kneeling as the hand of God appears (finely modelled and carefully executed figure);

f. 83v, (Ruth), Naked deity standing on a column;

f. 84v (prologue to Kings), Prophet writing (similar color scheme to the initial on f. 75v, but this is very stiff and less successfully executed);

f. 85v (chapter list, Kings), Standing king;

f. 86 (1 Kings), Standing king;

f. 97v, (2 Kings), King, shown upside-down (falling from power);

f. 106v, (chapter list, 3 Kings), Standing king;

f. 107v, (3 Kings), Seated king;

f. 117v, (chapter list, 4 Kings), Figure in a chariot drawn by two horses;

f. 161v (Jeremiah, prologue), Enthroned prophet holding an open book or tablet;

f. 162, (Jeremiah), Jeremiah in mourning;

f. 178v, (Lamentations), Annunciation;

f. 180, (Baruch), Seated figure;

f. 182, (Ezekiel, prologue), Two Israelites worshipping a bull before a man who falls to the ground;

f. 182v, (Ezekiel), The two spies carrying the cluster of grapes from the promised land;

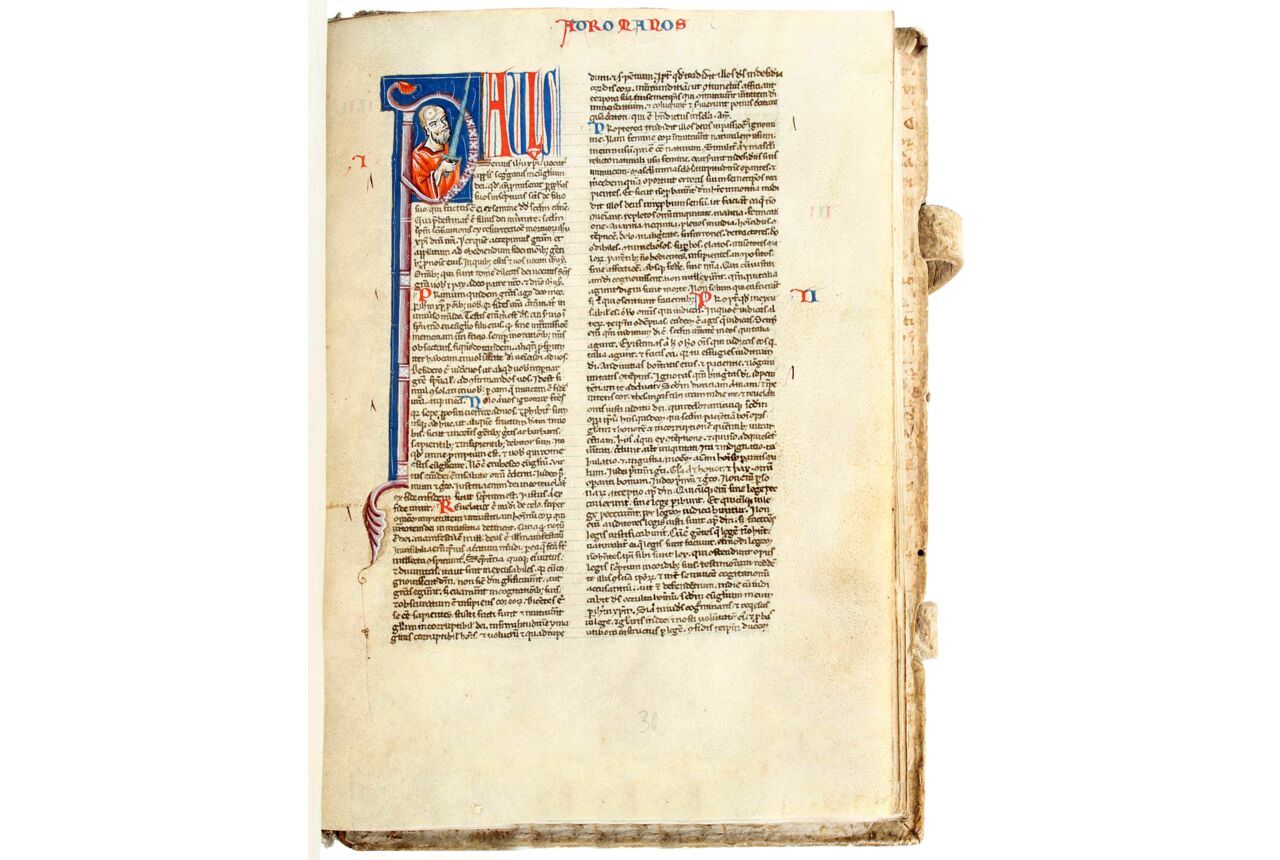

f. 297v, (Matthew), Matthew seated and writing his Gospel and looking directly at the viewer;

f. 307, (Mark), Mark standing in a column and holding his Gospel as a book, with his attribute, the lion, above him;

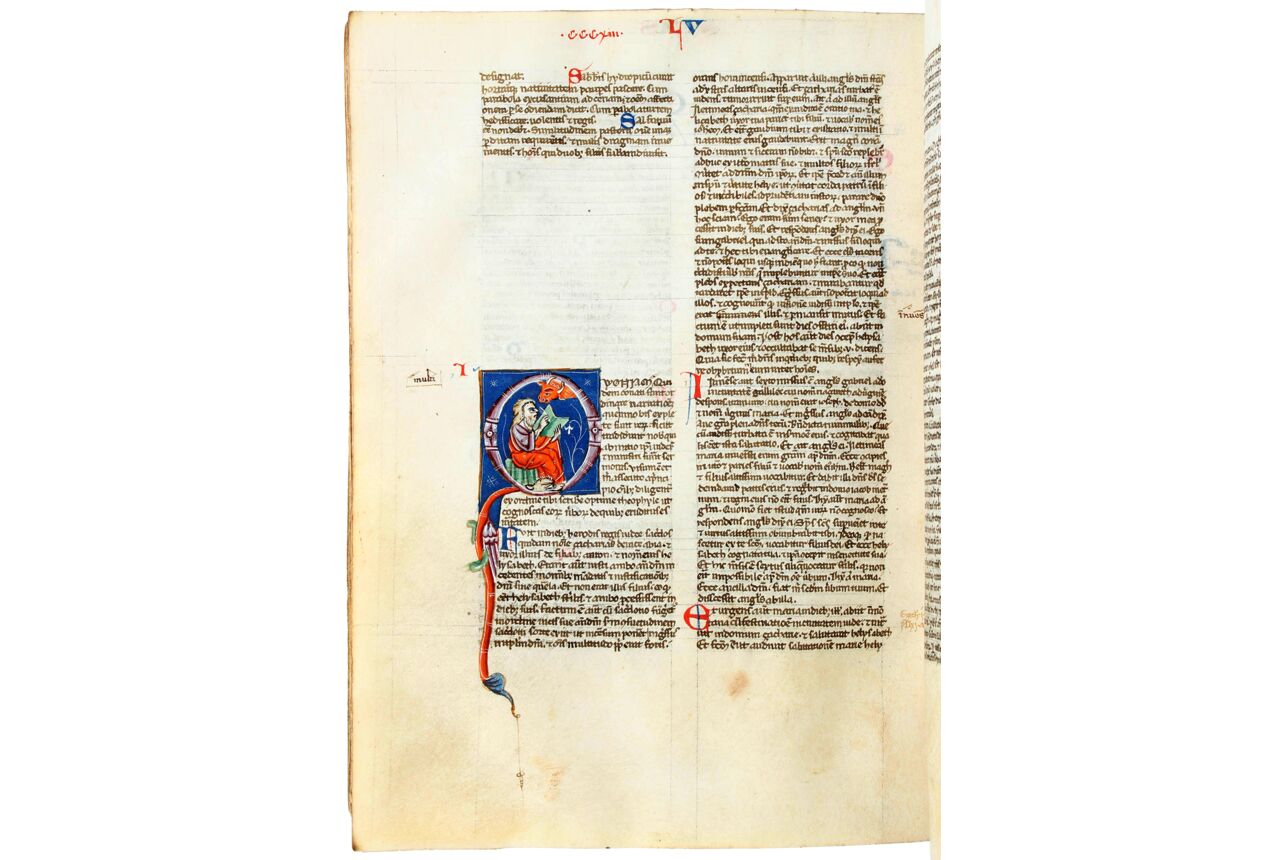

f. 313, (Luke), Luke, writing in an open book as his attribute, the bull, appears to him;

fol. 323v, (John), John, standing, below a tiny white eagle;

f. 342, (Romans), Paul with sword.

Fifteen smaller historiated initials with the face of Paul or another apostle (3- to 4-line): f. 331v, (Acts); f. 345v (1 Corinthians), f. 349 (2 Corinthians); f. 351v (Galatians); f. 352v (Ephesians); f. 353v (Philippians); f. 354v (Colossians); f. 355v (1 Thessalonians); f. 356 (2 Thessalonians); f. 356v (1 Timothy); f. 357v (2 Timothy); f. 358 (Titus); f. 358v (Philemon); f. 362v (1 Peter); f. 364v, (1 John).

Three distinct styles are found in this Bible’s illumination (although they are likely by more than three artists). The first style, found in the Old Testament through f. 182v, with the exception of the initial to Genesis, includes a series of historiated initials, 12- to 9-lines, with initials of various colors (red and blue, green, blue, pink) infilled and on polished gold grounds, heavily edged in black or with narrow colored frames; the figures within the initials are often dressed in deep blue with bright orange over tunics, both highlighted with groups of three small white dots. Often the figures are stiff, with very elongated skinny arms; the initial on f. 75v, although in this general style is very well executed and in excellent condition, with an expressive face and prominent eyebrows, and shaded skin tones; in other initials in this style, the faces are painted with large eyes and greenish skin tones (some faces appear to have been retouched). The illuminated initials in this section vary and show French influence (cf. ff. 55 and 56 with crude diaper patterns; and ff. 118v and the two initials on f. 129, which may be influenced by earlier French manuscripts and are particularly well-executed on pristine gold grounds). The brightly dressed figures, with their robes scattered with three dots, posed against polished gold grounds, can also be seen in Paris, BnF, MS Français 12473, a Chansonnier from Padua-Venice from the second half of the thirteenth century (the comparison is one of general similarity only (note the absence of bright red in our manuscript) (Online Resources; Molli, Mariani, Toniolo, 1999, cat. 11).

The Genesis initial stands apart from these initials and must be by another artist. It is executed with a much softer palette and with very broad strokes delineating the drapery; the faces of the figures have large eyes and greenish skin tones.

The third style is by a masterful artist(s), who executed a series of very attractive decorative initials, as well as the initials of the Evangelists before the Gospels and the depiction of Paul before the Letter to Romans. The initials are a distinctive violet or bright orange, with white highlights, against bright blue grounds, with well-balanced figures dressed in violet and bright orange with touches of acid green; drapery folds are highlighted in white. Byzantine influence is observable in the facial tones and features of the figures. The faces are very carefully executed; compare for example, St. Paul (Romans), with prominent eyebrows, a careful beard, with light gray used for modelling, and touches of red on the lips and cheeks. Many similarities in the facial features, drapery, and white details of the initials’ background can be found in Bodleian Library MS. Canon. Bibl. Lat. 56, a Bible sometimes ascribed to Bologna, but possibly from elsewhere in Northern Italy, dated 1265 and illuminated by a master known by some scholars as the “primo miniatore di Lanfranco de Pancis” (see for example ff. 255v and 257, Online Resources; Baldi, 2023; Conti, 1981, p. 21, pl. 13, 16). Some similarities may also be noted with Paris, BnF, MS lat 232 (Avril and Gousset, 1984, no. 4), and British Library, Egerton MS 2908 (Baldi, 2023, p. 8). The distinctive bold decorative initials might be compared with the initials in the Psalter at the Bodleian Library, MS Canon. Liturg. 370, dated 1266, Padua, copied by Giovanni da Gaibana and illuminated by the Gaibana master (the initial ‘d’; different palette, but with the same bold acanthus turned almost abstract).

The thirteenth century saw the development of a new physical format for the Bible, the portable or “pocket” Bible (often defined as Bibles that are less than 200 mm. in height) that decisively changed how the Bible was used and read, creating, for the first time in the Middle Ages, a book that was intended for individual use. The earliest examples of these very small (if somewhat chunky) one-volume Bibles were copied in Paris at the end of the 1220s or the early 1230s and the format was subsequently adopted throughout Europe. In Italy, most of the examples of these small Bibles date from the second half of the thirteenth century; our Bible, dating from the middle of the thirteenth century, is therefore an important early example. Apart from size, however, this Bible exhibits physical characteristics that are quite distinct from pocket Bibles copied in Paris, including the type of parchment, quire structure, and presence of clear breaks (or caesura) in the text. These breaks occur here at the end of 2 Maccabees on f. 270 (f. 270v is blank), at f. 295v, where the Old Testament ends on a leaf added to the quire, leaving part of column b blank, and at the end of Acts on f. 340v, where it is followed by a blank leaf (on caesura, see Ruzzier, 2015, pp. 163-167).

The text of our Bible is largely distinct from that other important thirteenth-century innovation, the Paris Bible (Light, 2012). Like the Paris Bible, this Bible is divided into modern chapters and includes the Interpretation of Hebrew Names. In all other respects, however, including the order of the books, prologues, and text, this manuscript diverges from French models. This evidence of independent textual traditions can be found in many (indeed most) thirteenth-century Italian Bibles (see Magrini, 2007; Light, 2012; Ruzzier, 2015 and 2018). A few features of this Bible’s text are especially noteworthy. The order of the books (Octateuch, Kings, Chronicles 1-2, Major Prophets (with Baruch), Minor Prophets, Psalms, Ezra-Nehemiah, Tobit, Judith, Job, Esther, Maccabees 1-2, Wisdom Books, Gospels, Acts, Pauline and Catholic Epistles, Apocalypse) is an unusual order; not listed in Berger, 1893, pp. 331-339 (nor does it seem modelled on any of the earlier Italian Giant Bibles studied in Lobrichon, 2016 pp. 257-258). The prologues in our Bible are not related to the Paris Bible prologues (note the absence of the six “new” prologues, characteristic of the Paris Bible), which is not uncommon in Italian Bibles. In general, however, this prologue set is quite restrained, omitting many prologues one might expect to find. The chapters are evidence that this Bible’s exemplar very likely dated before c.1230 at the latest. Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Josua, Judges, 1 and 3 Kings all begin with capitula lists, summary texts that are rarely found in Bibles after c.1230 (although they did have a revival in the fifteenth century). The chapter divisions here generally agree with “modern” chapters, but many of the books of the Bible also include additional, unnumbered divisions from different, older systems of chapters.

The signs of use in this Bible, which are plentiful, are one of its most interesting features, and will repay further study. Throughout, there are corrections to the text, marginal notes, and cross references to other books of the Bible. On f. 270, there is an added ars praedicandi, copied in a very tiny script at the end of Maccabees. This manuscript continued in active use in the fifteenth century, when it was owned by the Carthusians. Letters (‘a-h’, ‘p’ ‘f’ and ‘T’; and on f. 244v, “in refectorio”) marking Carthusian liturgical readings are found on ff. 237-244v (Tobit, Judith, and the beginning of Job, and then resuming in Esther on ff. 251-254v).

Literature

Avril, F., M.-T. Gousset, with C. Rabel. Manuscrits enluminés d'origine italienne. 2. XIIIe siècle, Paris, 1984.

Baldi, Camilla. “A Partire Dai Manoscritti Di Lanfranco De Pancis da Cremona. Un Itinerario Artistico,” Codex Studies 3 (2023), pp. 3-22.

01_Baldi.pdf

Berger, Samuel. Histoire de la Vulgate pendant les premiers siècles du Moyen Age. Paris 1893.

Conti, Alessandro. La Miniatura Bolognese: scuole e botteghe 1270-1340, 1981.

De Bruyne, Donatien. Sommaires, divisions et rubriques de la Bible latine : (1914). Belgium, 1914; reprint, Turnhout, 2014.

De Hamel, Christopher. The Book. A History of the Bible, London and New York, 2001, chapter 5, “Portable Bibles of the Thirteenth Century.”

Höfler, Karl Adolf Constantin. Geschichtschreiber der husitischen bewegung in Böhmen. Wien, 1865, pp. 267-278, no. 5.

Light, Laura. “The Thirteenth-Century Bible: The Paris Bible and Beyond,” The New Cambridge History of the Bible. Volume two, c. 600-1450, eds. Richard Marsden and E. Ann Matter, Cambridge, 2012, pp. 380-391.

Lobrichon, Guy. “Le succès ambigu des ‘Bibles atlantiques’. Triomphes et résistances dans

l’Ouest européen, XI e -XII e siècles,” Nadia Togni, ed. Les Bibles atlantiques: Le manuscript biblique à l’époque de la Réforme de l’Eglise du XI e siècle, Florence, 2016, pp. 247-281.

Magrini, Sabina. “Production and Use of Latin Bible Manuscripts in Italy during the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries,” Manuscripta 51.2 (2007), pp. 209-257.

Molli, Giovanna Baldissin, Giordana Canova Mariani, and Federica Toniolo, La miniatura a Padova: dal Medioevo al Settecento, Modena, 1999.

Murano, Giovanna. “Chi ha scritto le Interpretationes Hebraicorum Nominum?” in Étienne Langton, prédicateur, bibliste, théologien, eds. Louis-Jacques Bataillon, Nicole Bériou, Gilbert Dahan et Riccardo Quinto, Turnhout, Brepols, 2010, pp. 353-371.

Quentin, Henri. Mémoire sur l’établissement du texte de la Vulgate. Rome, 1922.

Ruzzier, Chiara. “Continuité et rupture dans la production des bibles au XIIIe siècle,” Chiara Ruzzier and Xavier Hermand, eds. Comment le Livre s’est fait livre : la fabrication des manuscrits bibliques (IVe-XVe siècle) : bilan, résultats, perspectives de recherche : actes du colloque international organisé à l’Université de Namur du 23 au 25 mai 2012, Turnhout, 2015, pp.155-168.

Ruzzier, Chiara. “Les manuscrits de la Bible au XIIIe siècle: quelques aspects de la réception du modèle parisien dans l'Europe méridionale,” in Medieval Europe in Motion. The Circulation of Artists, Images, Patterns and Ideas from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic Coast, Palermo, 2018.

Valagussa, G. “Il miniatore di Lanfranco de Pancis: un nuovo personaggio nella storia della miniatura duecentesca,” Arte Cristiana 81 (1993), pp. 323-336.

Online Resources

Vinzenz Werl, “Manuscripten-Catalog der Stifts-Bibliothek zu Göttweig I [in manuscript], Göttweig, 1843

https://manuscripta.at/diglit/werl_1/0202

Göttweig, Benediktinerstift, Cod. 961 (rot) / 877 (schwarz), “Catalogus Manuscriptorum Codicum,” Göttweig 1738 [this manuscript not recorded]

https://manuscripta.at/diglit/AT2000-961/0011

Göttweig, Benediktinerstift, Cod. 962a (rot) / 878 (schwarz), ”Catalogus Contentorum in Manuscriptis,” Göttweig 1756, listing this manuscript, f. 167v.

https://manuscripta.at/diglit/AT2000-962a/0340

Oxford, Merton College MS 206

https://medieval.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/catalog/manuscript_10304

Switzerland, Sion/Sitten, Archives du chapitre, MS 15

https://www.e-codices.ch/en/list/one/acs/0015

Paris, BnF, MS Français 12473

https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc13577n

Bodleian Library MS. Canon. Bibl. Lat. 56

https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/93044d53-1210-4d8e-8aef-728cfea8feae/

Bodleian Library, MS. Canon. Liturg. 370

Bodleian Library MS. Canon. Liturg. 370

TM 1380