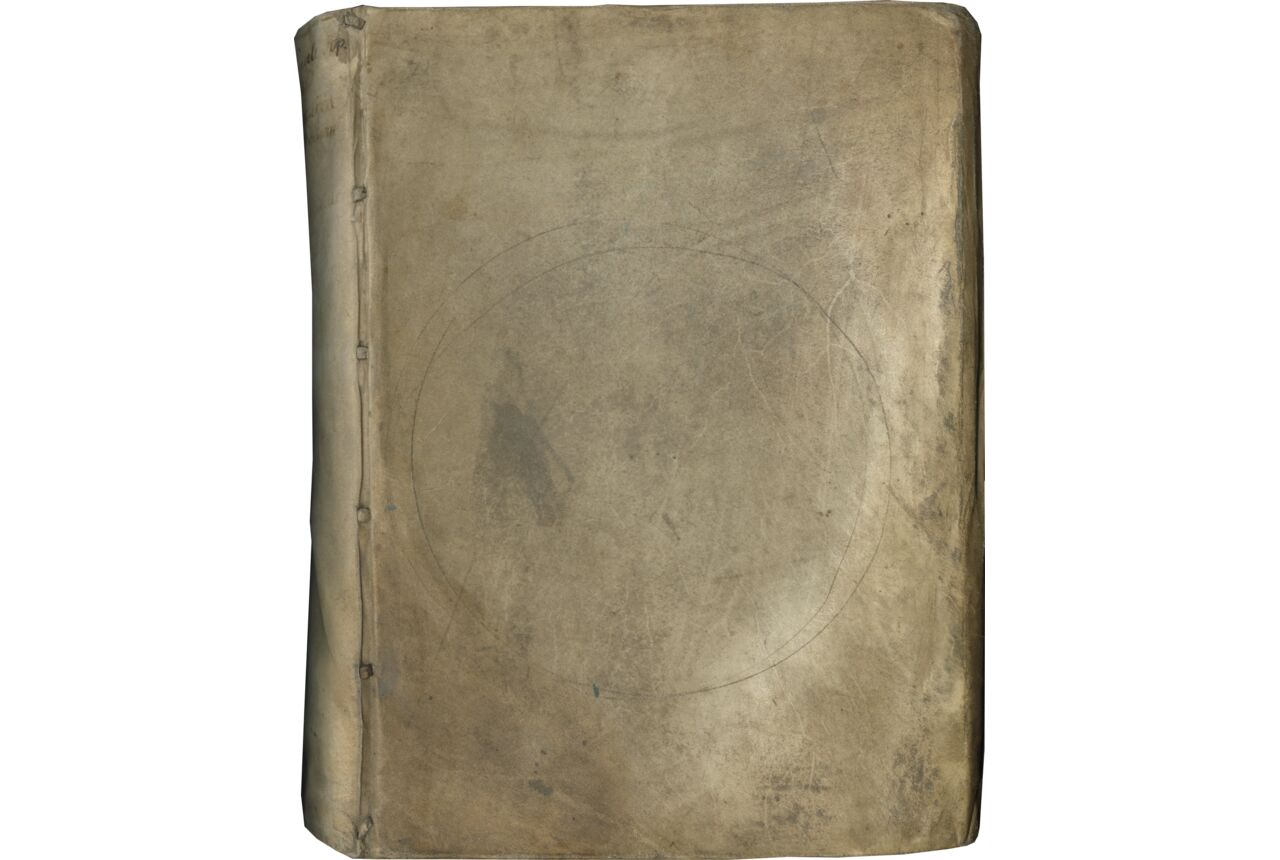

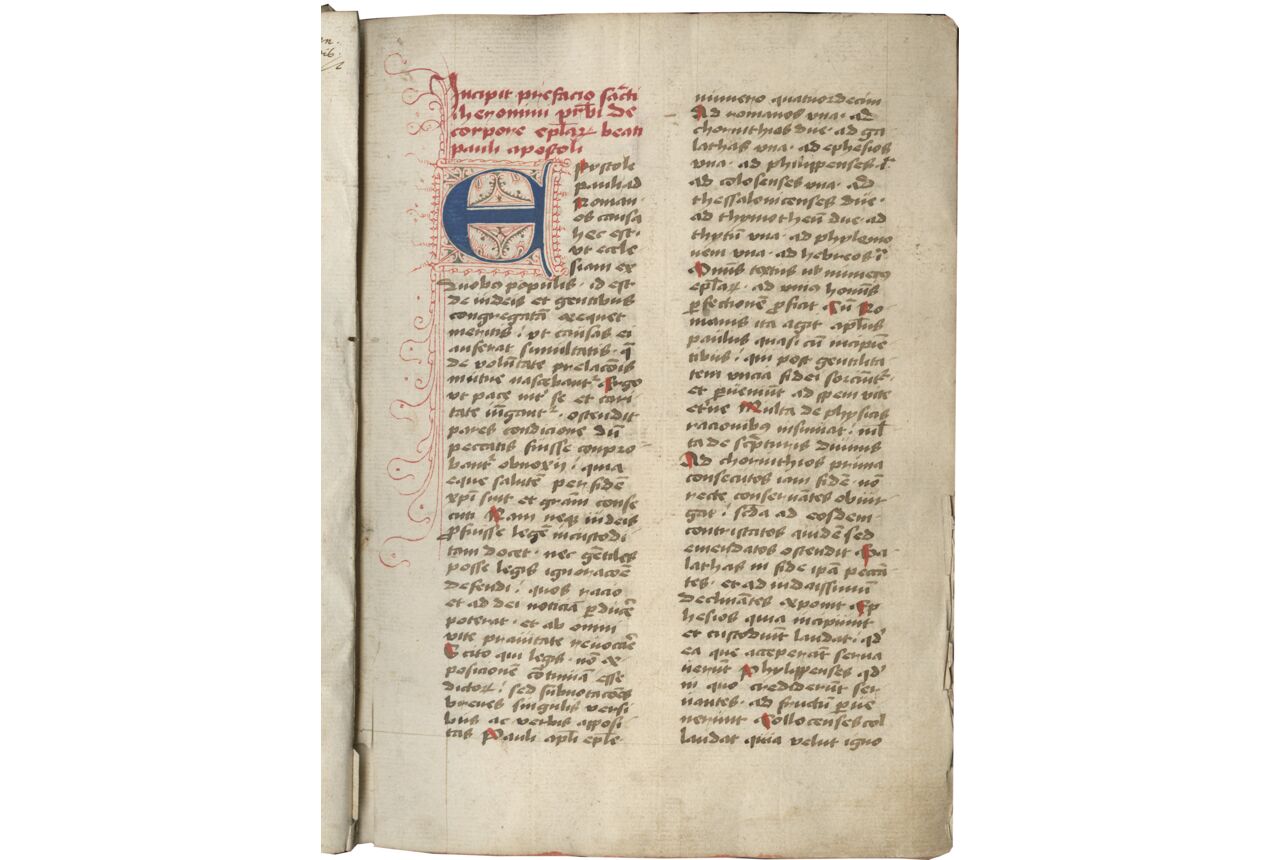

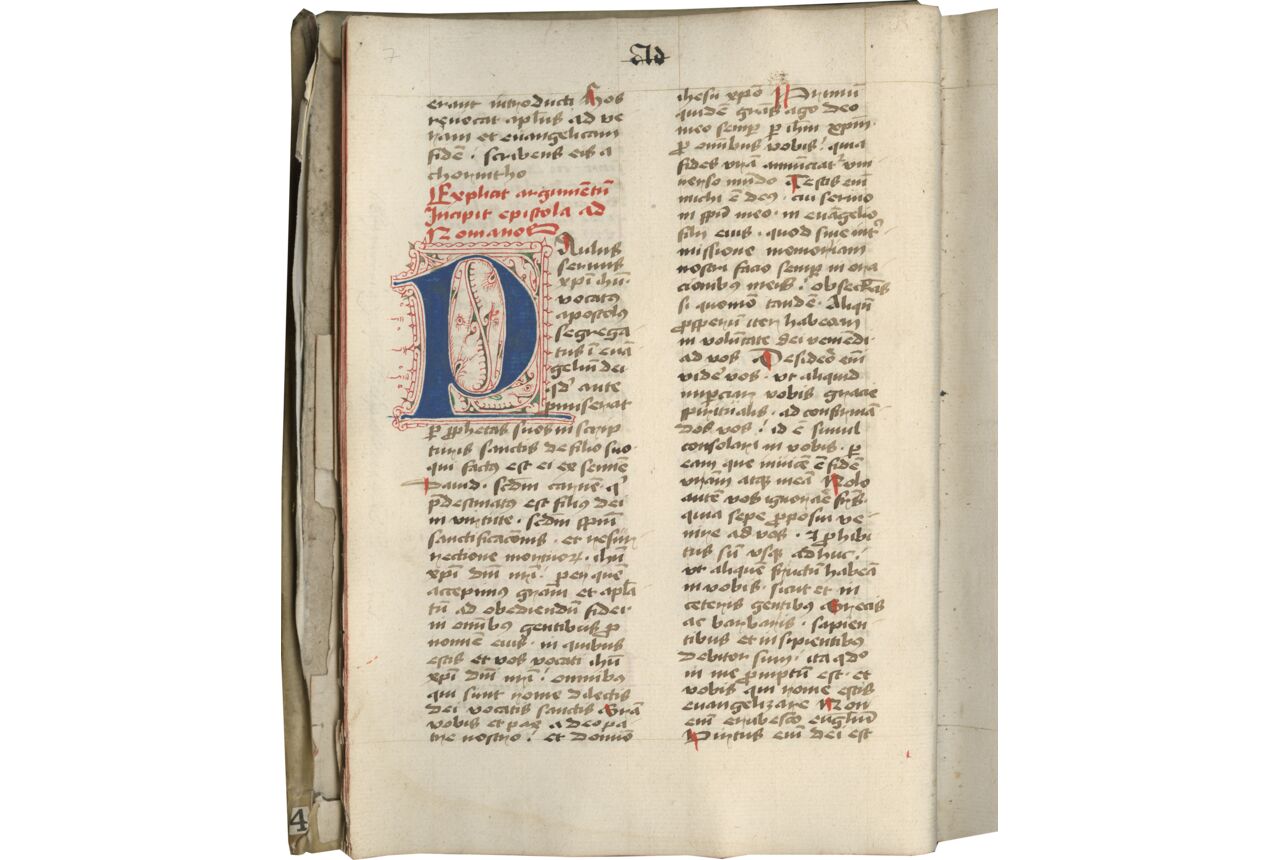

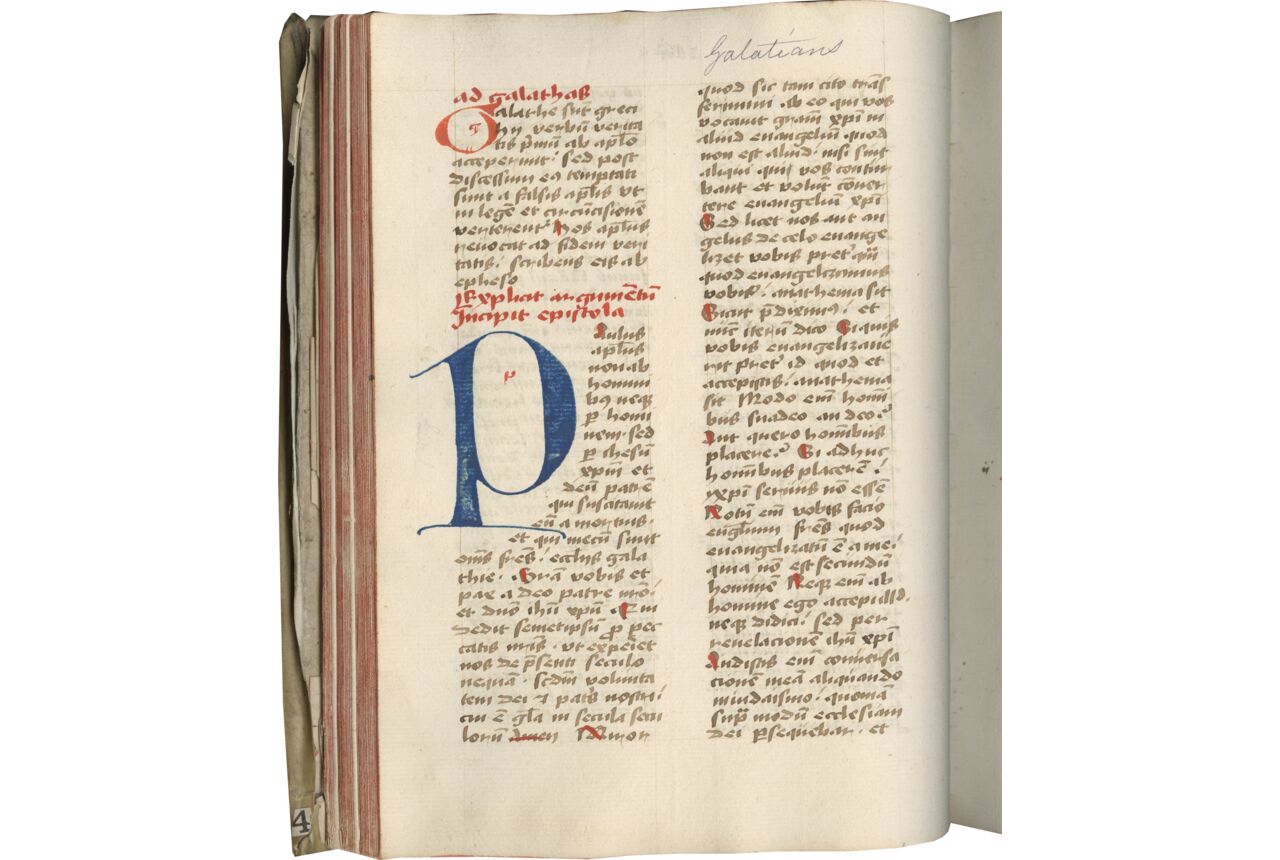

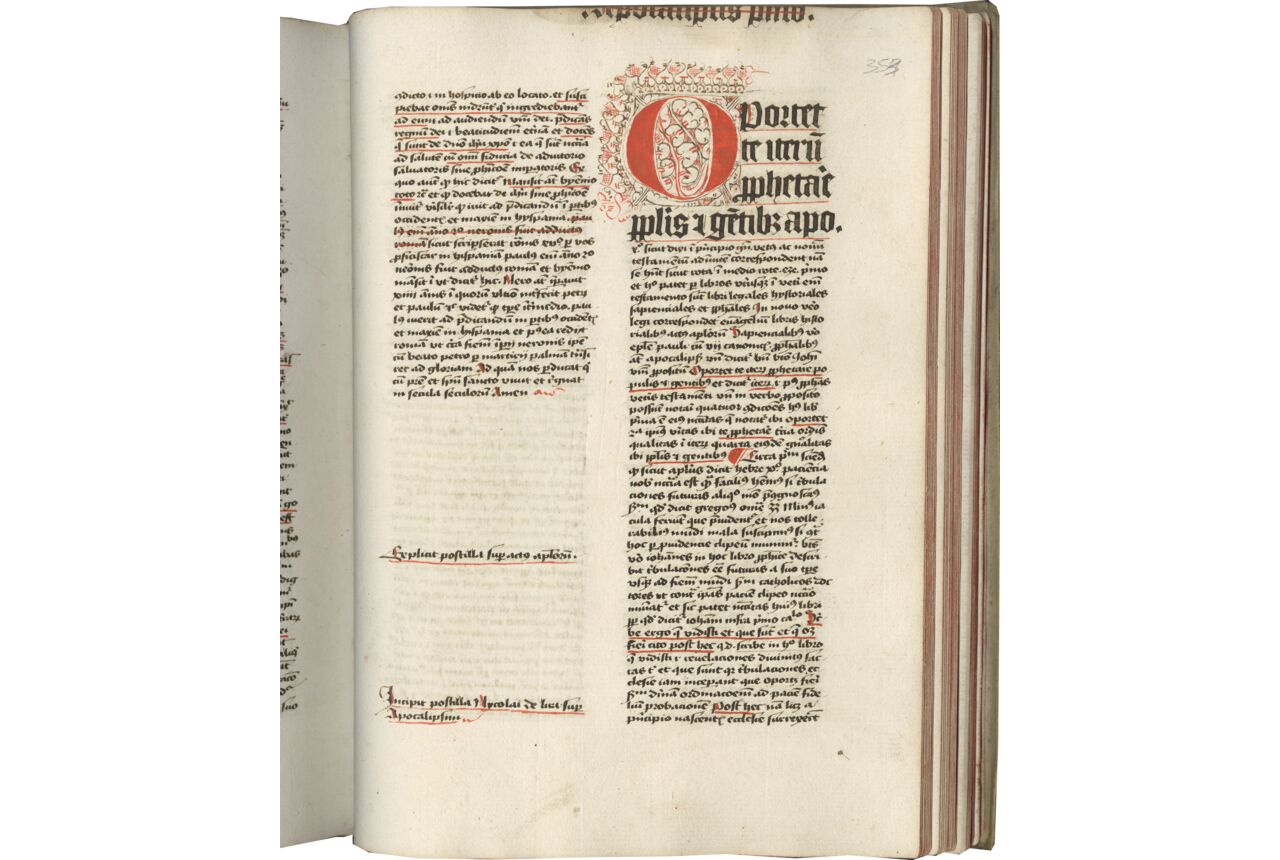

i (paper) + 383 + i folios on paper, watermarks, front and back flyleaves and ff. 1-145, letter ‘p’, very widespread, similar to Briquet Online no. 8525, Douai 1453, no. 8526, Cologne 1456 (with 10 others, to 1465), no. 8527 Quiévrain 1463 (with 20 others, to 1472), no. 8528, Siegen 1467 (with 15 others, to 1479), and no. 8529, Colmar 1471 (with 4 others, to 1476); ff. 146-end, vertical unicorn with striped horn, similar to Piccard Online no. 124379, Arnhem 1466-1467, no. 124378, Venloo 1463-1464, no. 124375, Friedburg 1459, no. 124417, n.p. 1465, and ‘y’ made with two lines with a cross above and cloverleaf on tail, similar to Piccard Online no. 30029, Arnhem 1462 (collation i-xi12 xii12+1 [through f. 145] xiii-xx12 xxi10 xxii-xxvii12 xxviii10 xxix-xxxii12), no catchwords or signatures, layout varies, ff. 1-145v, frame ruled lightly in ink (justification 210 x 140 mm.), written in a formal cursive gothic bookhand without loops in two columns of 38 lines, red rubrics, majuscules stroked with red, three-line red initials, nine- to fifteen-line blue or parted red and blue initials (occasionally with only the blue completed), usually with guide letters within the initial in red, two blue initials with finely-executed red pen work initials with touches of green, f. 1, seven lines, f. 6v, ten lines, added running titles, which continue to part two of the volume (some trimmed); ff. 146-end, apparently frame ruled very lightly in lead (justification 207-205 x 142-140 mm.), copied in a very neat controlled hybrida script in 48-51 long lines on ff. 146-153, and then continuing by the same scribe in two columns of 50-52 lines, with the biblical text at the beginning of chapters copied in a larger gothic bookhand, rubrics and biblical lemmata within the text underlined in red, a few red rubrics, red paraphs, majuscules within the text stroked with red, three- to ten-line red or occasionally blue initials, a few three- to four-line red initials with pen decoration in black,10-line red initial, f. 353, with red and black pen decoration, six 10-line parted red and blue initials, ff. 146 (with red pen work), 146v, 290 (with simple red penwork), 296v, 306, 316, in very good overall condition, f. 1, slit at the bottom inner margin, and frayed in the outer margin, ff. 145v-146, paper noticeably darkened (possibly the volume was displayed open for a long time), f. 383 frayed at the gutter, a few worm holes, rare stains from damp top margin in the second half, last few pages a bit fragile in the inner margin. Bound in seventeenth century(?) plain vellum over pasteboard with yap edges, reusing the original flyleaves and pastedowns, edges dyed red, vellum at the front now detached from the pasteboard and curling up, , front and back covers rather dirty and scuffed, title handwritten on spine (“Epistolae Pauli Apocalypsis Epistolae canonici, Actum, Apocalypsis,” with “Postillae” below), and a lighter square where a label has been removed, overall in good, sturdy condition. Dimensions 275 x 198 mm.

This sizeable volume combines a copy of the New Testament, lacking only the Gospels, with the Commentaries by Nicholas of Lyra on the same books of the New Testament. Although possibly of independent origin, these two sections are contemporary and were united very soon after they were copied. Fifteenth-century Bibles are uncommon, and copies of this fourteenth-century biblical commentary are always of interest. Nicolas’s continuing importance is summed up in the couplet: “If Lyra had not played, Luther could not have danced.” This is the only manuscript we know of that combines the two within one volume, but it is easy to see how readers benefited greatly by having these complementary texts together.

Provenance

1. Reconstructing how this volume came to be is not straightforward. Evidence of the watermark, script, and layout suggest the possibility of an independent origin for the biblical text (ff. 1-145v) and the postillae by Nicholas of Lyra (ff. 146-383), but they are contemporary or nearly so, and have clearly been together for a long time (the watermarks on the front and back flyleaves are the same ‘p’ found in the paper used for the biblical section of the manuscript).

Evidence of the script, decoration, and watermarks suggests the first part of the manuscript, with the biblical text was copied in Northwestern Germany, c. 1450-1475. It was copied in cursive gothic bookhands, without loops, by several scribes; the script of the first scribe in particular is quite slanted, with sharp pointed ‘d’, ‘e’, and single looped ‘a’, and shaded long ‘s’.

Evidence of the watermarks and script suggest the second half of the manuscript with Nicholas of Lyra’s postillae was likely copied in the Northeastern Netherlands or in Northwestern Germany, c. 1460-1470; its script is a small, very disciplined cursive gothic script, without loops, a hybrida script, of the type used so often in religious houses and monasteries associated with the Brethren of the Common Life in the in the fifteenth century from the second quarter of the century on.

Given the differences in the paper, layout, script, and decoration, it is possible that these two sections were of independent origins, but were united soon after both were copied, as noted above. However, other scenarios cannot be ruled out, particularly given how well these two texts work together in tandem. They could have been intended to be two parts of the same volume from the outset. Alternatively, and probably more likely, it is not impossible that the original owner acquired the New Testament (part one of the manuscript), and then arranged for the postillae to be copied to accompany the biblical text, or vice versa.

2. Mostly without marginalia, apart from ff. 290-291v, which includes a marginal commentary copied in a large and legible cursive script (a few letters trimmed).

3. Belonged to Johann Heinrich Joseph Niesert (1766-1841); front flyleaf, f. i verso, “Bibliotheca J. Niesert parochi in Velen 1816.” Niesert was a Catholic priest, and a collector of manuscripts and seals; he was born in Münster, and served in a parish in Velen, North Rhine-Westphalia; his collection was sold in 1843, and books and manuscripts in his collection can now be found in the British Library, the Bodleian Library, and in the Universitätsbibliothek in Münster.

4. Belonged to Isaac H. Hall, inscription, inside front cover, and inside back cover.

5. Belonged S. B. Pratt, in pencil, front flyleaf recto; brief description of the manuscript in English in pencil below in another hand.

Text

I. ff. 1-145v:

ff. 1-74, Incipit prefacio sancti iheronimi presbyteri de corpore epistolarum beati pauli apostoli, incipit, “Epistole pauli ad Romanos causa hec est … [Stegmüller 651]; Item alius prefacio, incipit, “Primum queritur …” [Stegmüller 670]; Argumentum …, incipit, “Romani sunt qui ex iudeis …” [Stegmüller 6355; de Bruyne, Prefaces, pp. 215-217]; f. 3v, Capitula to Romans [De Bruyne, Sommaries, pp. 314-319, ‘M’]; Capitula to 1 Corinthians, [de Bruyne, Sommaires, pp. 320-326, ‘A’]; f. 6, Incipit argumentum ad corinthios epistole ad romanos. Capitula reliquarum epistolarum quere post epistola, incipit, “ Romani sunt partis ytalie … [Stegmüller 677]; f. 6v, Romans; f. 19, [prologue to 1 Corinthians], incipit, Corinthii sunt achaici … [Stegmüller 685]; f. 19, 1 Corinthians; f. 31, [prologue to 2 Corinthians] Post actam [Stegmüller 699]; f. 31, 2 Corinthians; f. 39v, [prologue to Galatians] Galathe sunt greci [Stegmüller 707]; f. 39v, Galatians; f. 43v, [prologue to Ephesians] Ephesii sunt asiani [Stegmüller 715]; f. 43v, Ephesians; f. 47v, [prologue to Philippians] Philippenses sunt macedones [Stegmüller 728]; f. 47v, Philippians; f. 50, [prologue to Colossians] Colocenses et hii [Stegmüller 736]; f. 50v, Colossians; f. 53, Laodicenses; f. 53v, [prologue to 1 Thessalonians] Thessalonicenses sunt macedones [Stegmüller 747]; f. 53v, 1 Thessalonians; f. 56, [prologue to 2 Thessalonians] Ad thessalonicenses [Stegmüller 752]; f. 56, 2 Thessalonians; f. 57v, [prologue to 1 Timothy] Timotheum instruit [Stegmüller 765]; f. 57v, 1 Timothy; f. 60v [prologue to 2 Timothy] Item Timotheo scribit [Stegmüller 772]; f. 60v, 2 Timothy; f. 63, [prologue to Titus] Titum commonefacit [Stegmüller 780]; f. 63, Titus; f. 64, [prologue to Philemon] Philemoni familiares [Stegmüller 783]; f. 64, Philemon; f. 65, [prologue to Hebrews] In primis dicendum [Stegmüller 793] ; f. 65, Hebrews;

ff. 74v-79, Capitula lists for 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians [De Bruyne, Sommaires, pp. 328-341, ‘A’]; for Philippians, Colossians, Thessalonians 1 and 2, Timothy 1 and 2, Titus, Philemon, Hebrews [De Bruyne, Sommaires, pp. 343, 347, 349, 351, 353, 357, 361, 363, 363-365, ‘B’]; for the Catholic Epistles, omitting 3 John [De Bruyne, Sommaires, 382-390, ‘A’; ending mid-col. A, f. 79, remainder and f. 79v, blank, apart from the rubric to the Apocalypse];

ff. 80-145v, [prologues to Apocalypse], Apocalipsis Iohannis [Stegmüller 829]; Apocalipsis Iohannis tot habet [Stegmüller 829]; Iohannes apostolus [Stegmüller 834 or 835]; Iohannes apostolus filius Zebedei [Stegmüller 836]; f. 80v, Capitula list to the Apocalypse [De Bruyne, Sommaires, pp. 392-396, ‘A’]; f. 81v, Apocalypse; f 96v, [prologue to Catholic Epistles] Non ita ordo est [Stegmüller 809]; f. 97, James; f. 100v, 1 Peter; f. 103v, 2 Peter; f. 106, 1 John; f. 109, 2 John; f. 109v, 3 John; f. 110, Jude; f. 111v, [prologues to Acts] Lucas natione syrus [Stegmüller 640]; f. 111v, Actus apostolorum [Stegmüller 631]; f. 111v, [Capitula list to Acts, De Bruyne, Sommaires, pp. 370-380, ‘A’]; f. 113v, Acts.

Jude ends bottom col. a, f. 111, with “Et sic est finis apocalipsis” written at the top of col. b.

A copy of the New Testament lacking only the Gospels. The fifteenth century saw the revival of Bibles copied in relatively large formats. There is currently no detailed study of this important phenomenon, nor is there a complete census of the surviving manuscripts. In the case of our manuscript, we can note the biblical books are arranged in an unusual order: beginning with the Pauline Epistles (including the apocryphal Epistle to the Laodiceans), Apocalypse, Catholic Epistles, and concluding with Acts. Textually, few fifteenth-century Bibles have been the subject of scholarly examination. However, it is interesting that in terms of the order of the biblical books and choice of prologues, this Bible is not related to the Bibles copied for the Windesheim congregation (as represented by Darmstadt, Hessische Landes- und Hochschulbibliothek, MS 324, copied by Thomas a Kempis in Zwolle at Agnietenberg between 1427 and 1439; see also Greitemann, 1937), nor is it related to the to the thirteenth-century Paris Bible.

The text is divided into the chapters still used today, which were widely adopted beginning in the thirteenth century after c. 1230. However, the Pauline and Catholic Epistles and Acts are also accompanied by chapter lists (summary texts that correspond to systems of chapters found in Bibles in the twelfth century and earlier). Chapter lists (also called capitula lists) are not uncommon in fifteenth century Bibles, an interesting return to texts that went out of fashion in the thirteenth century.

II. ff. 146-383v:

ff. 146-289v, incipit, “Ecce descripsi eam tibi tripliciter. Prov. 22. Quod verbum de sapientie descriptione dicitur …; [f. 146v], Paulus servus ….; Hec epistola dividitur in tres partes … in secula seculorum, Amen,” Explicit postilla super epistolam ad romanos; [f. 171v], Incipit postilla super epistolam ad corinthios, incipit, “Paulus vocatus ...; Hic incipit secunda pars epistolarum Pauli …”; [f. 200], Incipit secunda ad eosdem, incipit, “Paulus apostolus …; Postquam apostolus scripsit …”; [f. 216v], Incipit epistola ad galathas, incipit, “Paulus apostolus …; Hec epistola in tres partes …”; [f. 224], Incipit, epistola ad ephesios, incipit, “Paulus apostlus …; Hic incipit epistola pauli ad ephesios …”; [f. 229v], Sequitur epistola ad philipenses, incipit, “Paulus et tymotheus; Hic incipit epistola pauli ad philipenses …”; [f. 233v], Incipit epistola ad colocensis [sic], incipit, “Paulus apostolus …; Hic incipit epistola ad colosenses …”; [f. 238], Incipit epistola ad thessalonicensis prima, incipit, “Paulus et siluanus …; Hic incipit epistola prima ad thessalonicensis …; [f. 242], incipit, “Paulus et siluanus; Hic incipit secunda epistola …”; [f. 244], Incipit epistola, incipit, “Paulus apostolus …; Hic incipit epistola prima ad thymotheum …”; [f. 250], Incipit epistola secunda ad thymotheum, incipit, “Paulus apostolus …; Hic incipit secunda epistola ad thymotheum …”; [f. 253v], incipit, “Paulus seruus …; Hic incipit epistola pauli ad tytum …”; [f. 256], Sequitur epistola ad philemonem, incipit, “Hic incipit epistolam ad philemonem …”; [f. 256v], Incipit epistola ad hebreos, incipit, “Cum venerit …; In primitiva ecclesia …,” Expliciunt postille super epistolas pauli edite per fratrem Nycolaum de lyra ordinis minorum magistrum in theologiam;

Nicholas of Lyra, Postillae on the Pauline Epistles, Stegmüller 5902-5915; Galatians-Hebrews preceded by prologues (without commentary) Stegmüller 707, 715, 728 or 730, 736, 747, 752, 765, 772, 780, 783, 793.

f. 289v, incipit, “Augustinus. Si unus homo omnium hominum peccata … non denegaret”;

Short quotation from Ludolphus of Saxony, Vitae christi, copied following the explicit above (and similarly underlined in red); cf. Ludolphus, Vita Jesu Christi. Lugdunum, 1644, part 2, chapter IX, p. 410.

ff. 290-316, incipit, “Quatuor [sic] sunt minima …, Prov. 30; Septem epistole que canonice …; Jacobus ihesu christi. Liber iste dividitur …; [f. 296], Incipit super canonicas petri apostoli, incipit, “Petrus apostolus. Hec est secunda pars principalis …; [f. 302], Incipit super secundam, incipit, “Symon petrus seruus et apostolus. Hic incipit secunda petri epistola ….”; [f. 306], Sequitur canonica Iohannis prima, incipit, “Quod fuit ab inicio. Hic incipit tertia pars principalis …; [f. 312v], Sequitur secunda epistola Iohannis. Finita prima, incipit, “Senior electe domine. Postquam beatus Iohannes …”; [f. 313v], Incipit tertia epistola Johannis apostoli, incipit, “Senior gaio karissimo. Hec epistola sicud …”; [f. 314], Incipit epistola beati Jude apostoli, incipit, “Iudas ihesu chrsiti seruus. Hic incipit epistola beati Jude …”; Explicit postille super epistolas canonicas nycolai de lyra ordinis minorum doctoris sacre theologye. Deo laus de ominous donis suis;

Nicholas of Lyra, Postillae on the Catholic Epistles, Stegmüller RB 5916-5922.

ff. 316-353, Incipit postilla Nycolai de lyra super actus apostolorum prologus, incipit, Repleti sunt omnes spiritu sancto ... Actuum primo secundo sicut lex euangelica … in secula seculorum,” Explicit postilla super actus apostolum;

Nicholas of Lyra, Postillae on Acts, Stegmüller, 5901.

ff. 353-383v, Incipit postilla Nycolai de lira super Apocalipsim, incipit, “Oportet te iterum prophetare populis et gentibus. Apoc. 10. Sicut dixi in principio Genesis, vetus et novum testamentum ad invicem correspondent … cum omnibus nobis amen,” Explicit postilla nicolai de lira super apocalipsim.

Nicholas of Lyra, Postillae on the Apocalypse, Stegmüller 5923.

Nicholas of Lyra, Commentaries on the Pauline Epistles, Catholic Epistles, Acts, Apocalypse.

The Postillae were very popular, and survive in at least 800 manuscripts, and likely more (Stegmüller, 1950-1980, nos. 5829-5923, with a partial list of c. 200 manuscripts; Gosselin, 1970; Krey and Smith, 2000, p. 8).

There is no complete modern edition of these commentaries. Nicholas’s commentary encompassed the entire Bible; only the Song of Songs has been edited by a modern scholar (Kiecker, 1998); his Apocalypse commentary has been translated into English (Krey, 1997). The Strasbourg 1492 edition of the Postillae on the entire Bible is available in a reprinted edition, and online (Frankfurt am Main, 1970; Online Resources). Nicholas composed the work c. 1322-1331, drawing no doubt on his earlier the lectures on the Bible that he prepared for his students in Paris. It was the first biblical commentary to appear in print (Rome, 1471), and then in more than one hundred editions until 1600, including editions in Basel, Douai, Cologne, Lyons, Nuremberg, Paris, Venice and Strasbourg; Anton Koberger in Nuremberg, printed this work seven times from 1479-1497 (Gosselin, 1970).

The commentaries survive both in impressive multi-volume manuscripts that include the commentaries on the entire Bible (many of these expensive, illuminated copies) and in manuscripts that include the commentary on a single book of the Bible, or a group of books. Our manuscript includes all the books of the New Testament except for the Gospels. As is the case in most manuscripts, the text is copied as a continuous commentary, interspersed with the biblical lemmata, underlined in red. What makes our copy unusual is the fact that the volume begins with the New Testament text (again without the Gospels), without commentary. Combining the text of the Bible and the text of Nicholas’s commentaries within one volume is, to our knowledge, very rare indeed (we know of only this one example), but one can imagine that users of this volume benefited greatly by having both these complementary texts at hand in one convenient volume.

Nicholas of Lyra, O.F.M., (c. 1270-1349) was one of the greatest biblical scholars of the fourteenth century; indeed, many consider him one of the greatest biblical scholars of the Middle Ages. He was born in Lyre, near Évreux in Normandy. At the age of thirty, around 1300, he entered the Franciscan convent at Verneuil, and was soon sent to the Franciscan house in Paris to study at the University; the remainder of his life was spent in Paris. He became a regent master in theology in 1308/09, and later the Franciscan provincial minister for the Province of Paris from 1319-1324, and the provincial minister for Burgundy from 1324-1330.

Nicholas’s greatest work was his running commentary on the whole Bible, the Postilla litteralis in vetus et novum testamentum (The Literal Postil on the Whole Bible). He stresses the importance of the literal sense of the scriptures, which he argues was often neglected by other commentators, and discusses the grammar, philology, and historical context of the text. “Postilla,” a term which may derive from “post illa verba” (after that word), refers to a commentary written out as a continuous gloss, interspersed with scriptural lemmata. Throughout this commentary, he exhibits a thorough grounding in Jewish commentaries on the Bible, including the Talmud, the Midrash, and the works of Rashi (Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac), (1045-1105), and a knowledge of Hebrew. Scholars have suggested that he studied with Jewish scholars in Évreux, which was an important center of Jewish learning in the late thirteenth century, although more recently it has been suggested that he studied Hebrew in Paris (Klepper in Krey and Smith, eds., 2000, pp. 289-312; Geiger in Dahan, ed., 2011, 167-203). The influence of the Postillae extended far beyond the Middle Ages, and they were valued by Martin Luther and others. The often-cited little couplet, attributed to Julius von Pflug (1499-1564), “Si Lyra non lyrasset/ Lutherus non saltasset” (If Lyra had not played, Luther could not have danced), aptly summarizes the importance of Nicholas of Lyra’s thought to Martin Luther.

Literature

Dahan, Gilbert, ed. Nicolas de Lyre franciscain du XIVe siècle exégète et théologien, Collection des Études Augustiniennes. Série Moyen Âge et Temps Modernes 48, Paris, 2011.

De Bruyne, Donatien. Prefaces to the Latin Bible, Studia traditionis theologiae 19, Turnhout, 2015 [Originally published as: Préfaces de la Bible Latine, Namur, 1920].

De Bruyne, Donatien. Summaries, divisions and rubrics of the Latin Bible, Studia traditionis theologiae 18, Turnhout, 2014 [Originally published as: Sommaires, divisions et rubriques de la Bible latine, Namur, 1914].

De Hamel, Christopher. The Book: A History of the Bible, London and New York, 2001.

Gosselin, E. A. “A Listing of the Printed Editions of Nicolaus de Lyra,” Traditio 26 (1970), pp. 399-426.

Halperin, Herman. Rashi and the Christian Scholars, Pittsburg, 1963.

Kiecker, James George, ed. and trans. Nicholas of Lyra. The Postilla of Nicholas of Lyra on the Song of Songs, Milwaukee, 1998.

Klepper, Deeana Copeland. “The Dating of Nicholas of Lyra's Quaestio de adventu Christi,” Archivum Franciscanum Historicum 86 (1993), pp. 297-312.

Klepper, Deeana Copeland. The Insight of Unbelievers; Nicholas of Lyra and Christian Reading of Jewish Text in the later Middle Ages, Philadelphia, 2007.

Klepper, Deeana Copeland. “Nicholas of Lyra and Franciscan Interest in Hebrew Scholarship,” Krey and Smith, eds., 2000, pp. 289-312.

Krey, Philip D. W., transl. Nicholas of Lyra. Nicholas of Lyra's Apocalypse Commentary, Kalamazoo, Michigan, 1997.

Krey, Philip D. W. and Lesley Smith, eds. Nicholas of Lyra: the Senses of Scripture, Leiden and Boston, 2000.

Krey, Philip D. W. “The Eschatology of Nicholas of Lyra in the Apocalypse Commentary of 1329,” in Dahan, ed., 2011, pp. 153-165.

Nicholas of Lyra. Postilla super totam Bibliam, Frankfurt am Main, 1971 (reprint of the Strasbourg 1492 edition).

Stegmüller, Fridericus. Repertorium biblicum medii aevi, Madrid, 1950-1961, and Supplement, with the assistance of N. Reinhardt, Madrid, 1976-80.

Wood, James D. The Interpretation of the Bible: A Historical Introduction, London, 1958.

Online Resources

Briquet Online

http://www.ksbm.oeaw.ac.at/_scripts/php/BR.php

Sales catalogue Johann Niesert, Catalogus exquisitae bibliothecae pastoris Niesert Velenae defuncti … 1843 per commissarium B. Diekhoff … vendetur, Borken, 1842 (our manuscript, and perhaps none of his manuscripts, are included)

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=l1EVAAAAQAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA8

Repertorium biblicum medii aevi (digital version of Stegmüller)

http://repbib.uni-trier.de/cgi-bin/rebihome.tcl

Johannes Froben and Johannes Petri, ed., Basel, 1498

http://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/content/titleinfo/5083763

PDF of fifteenth-century editions of the Postillae (Julian of Norwich website)

http://www.umilta.net/nicholalyra.html

Plassmann, Thomas. “Nicholas of Lyra,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 11, New York, 1911

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11063a.htm

TM 1089