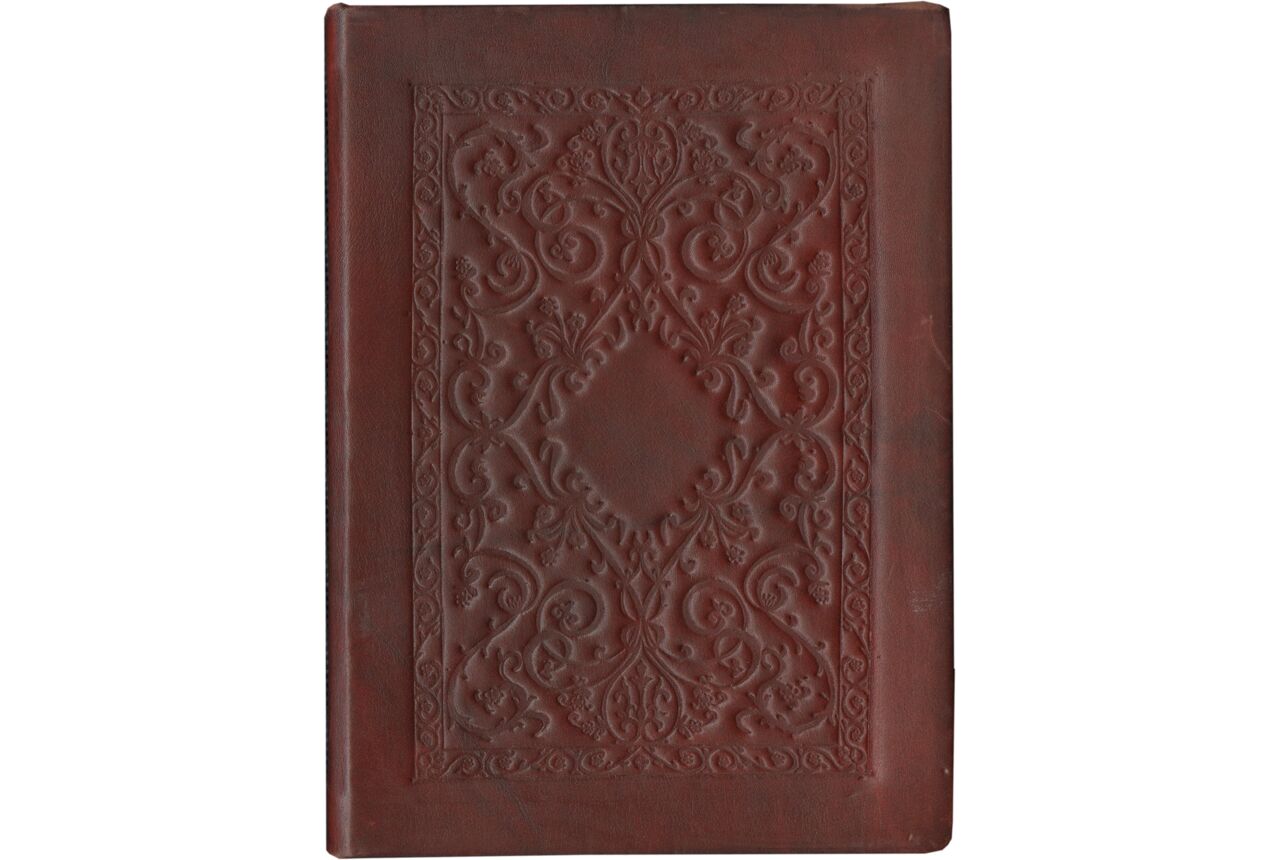

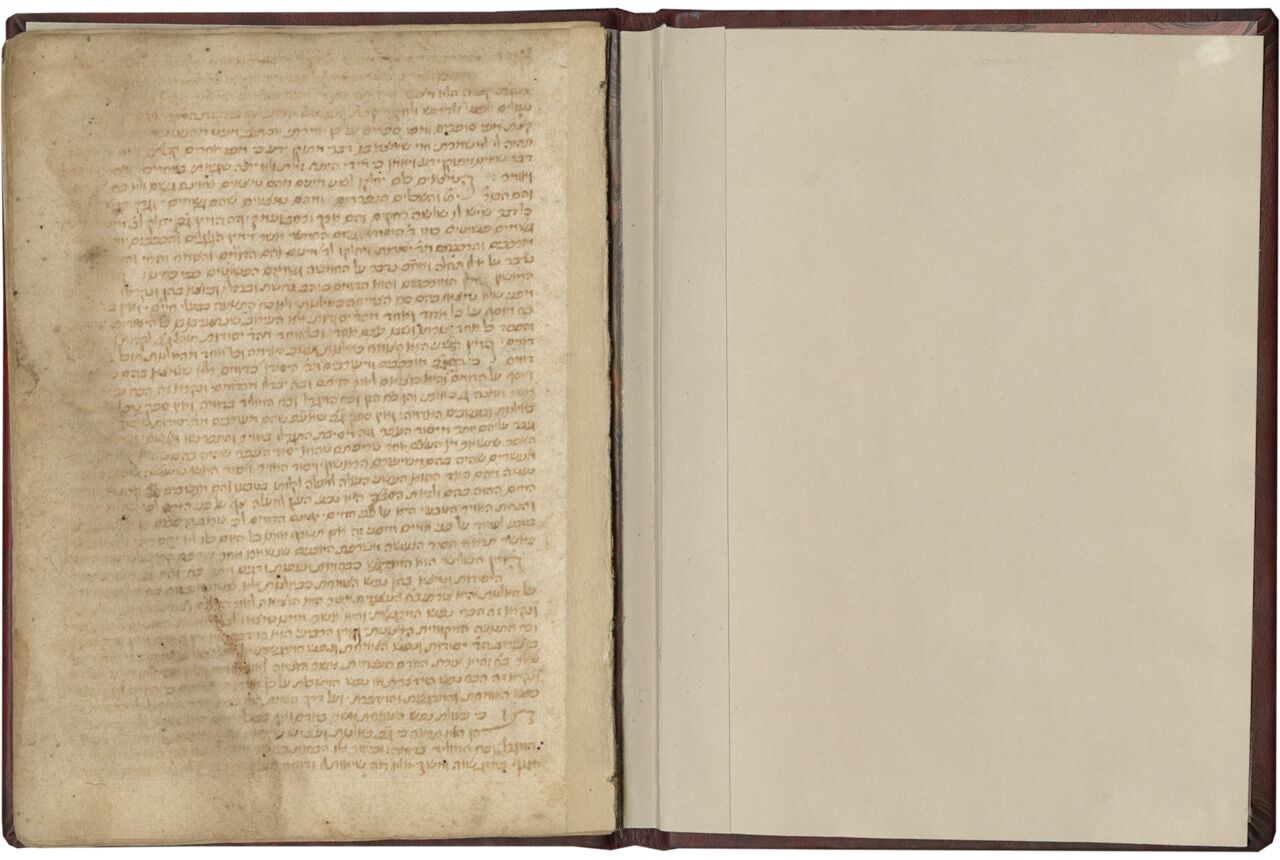

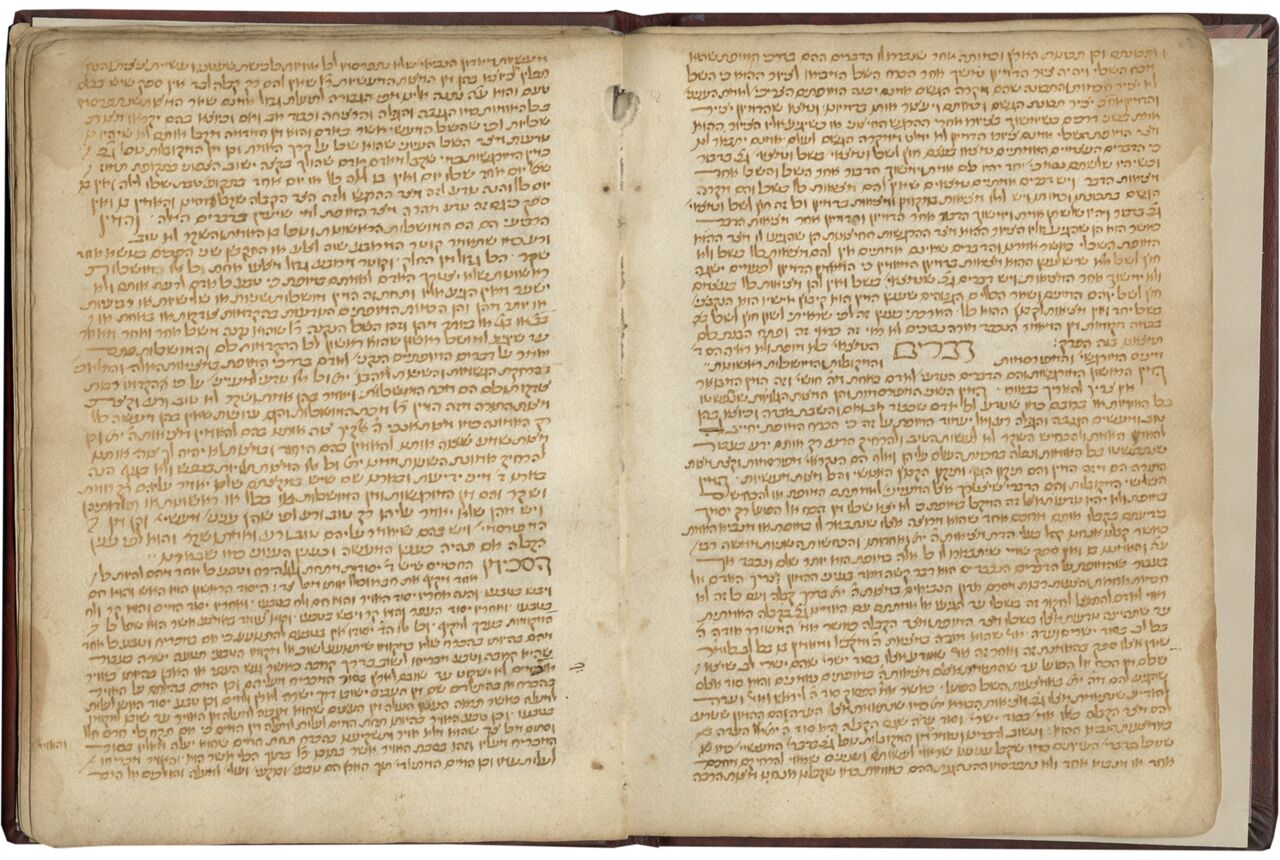

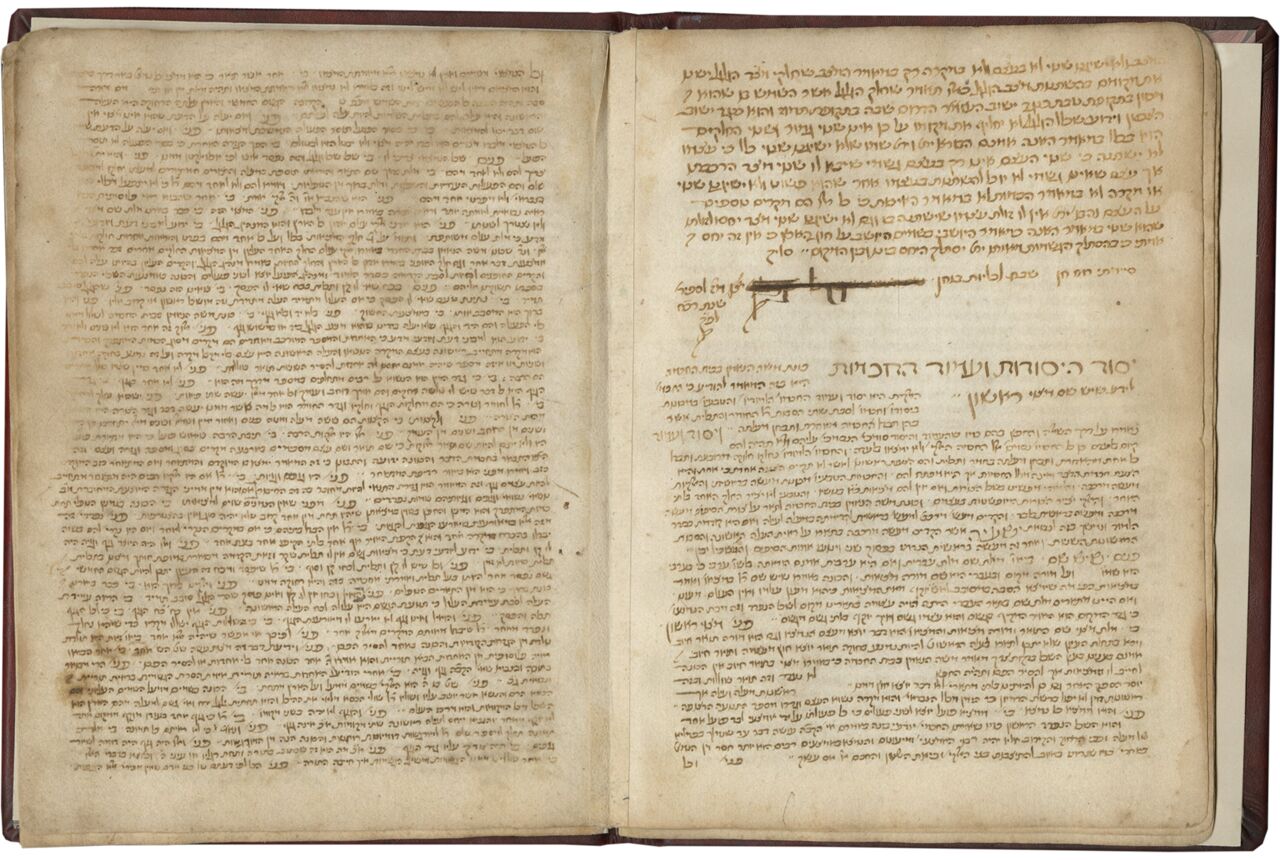

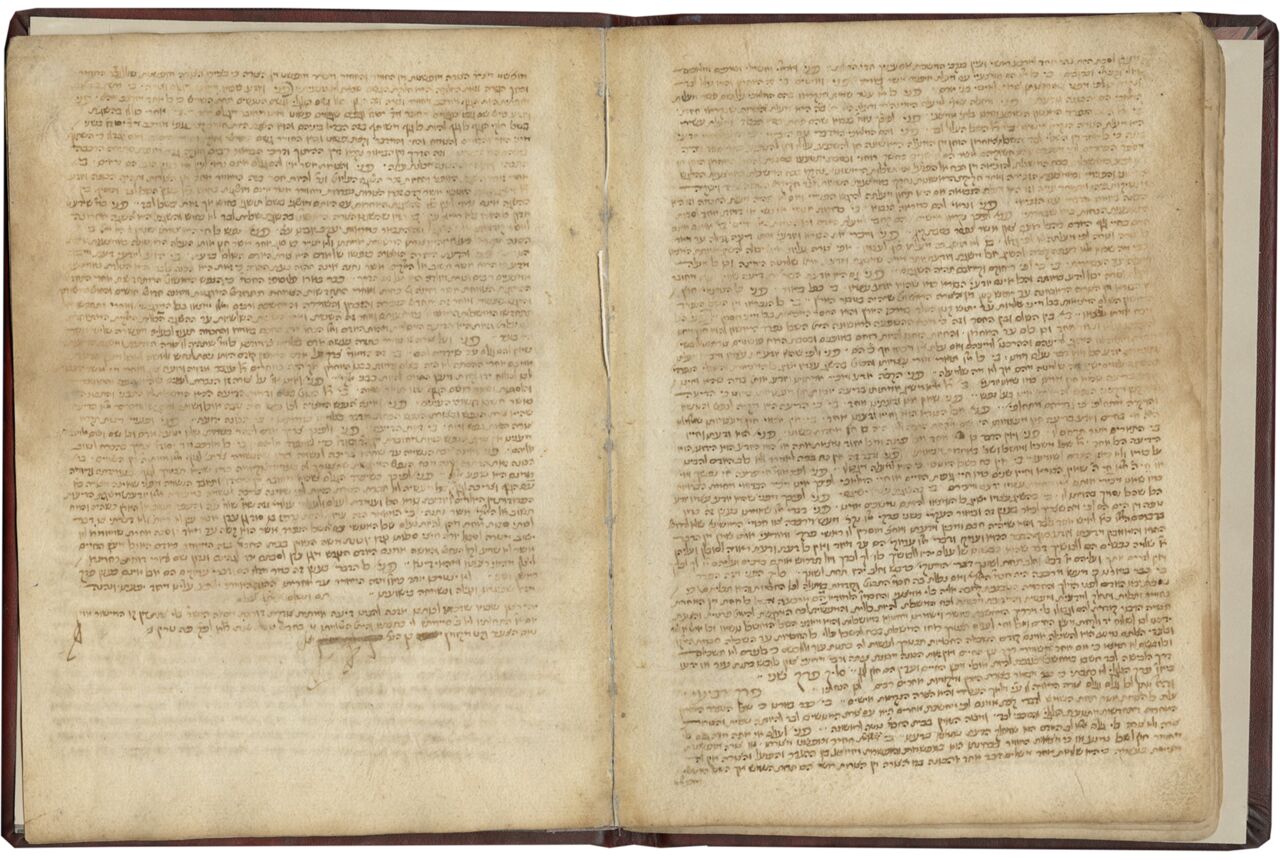

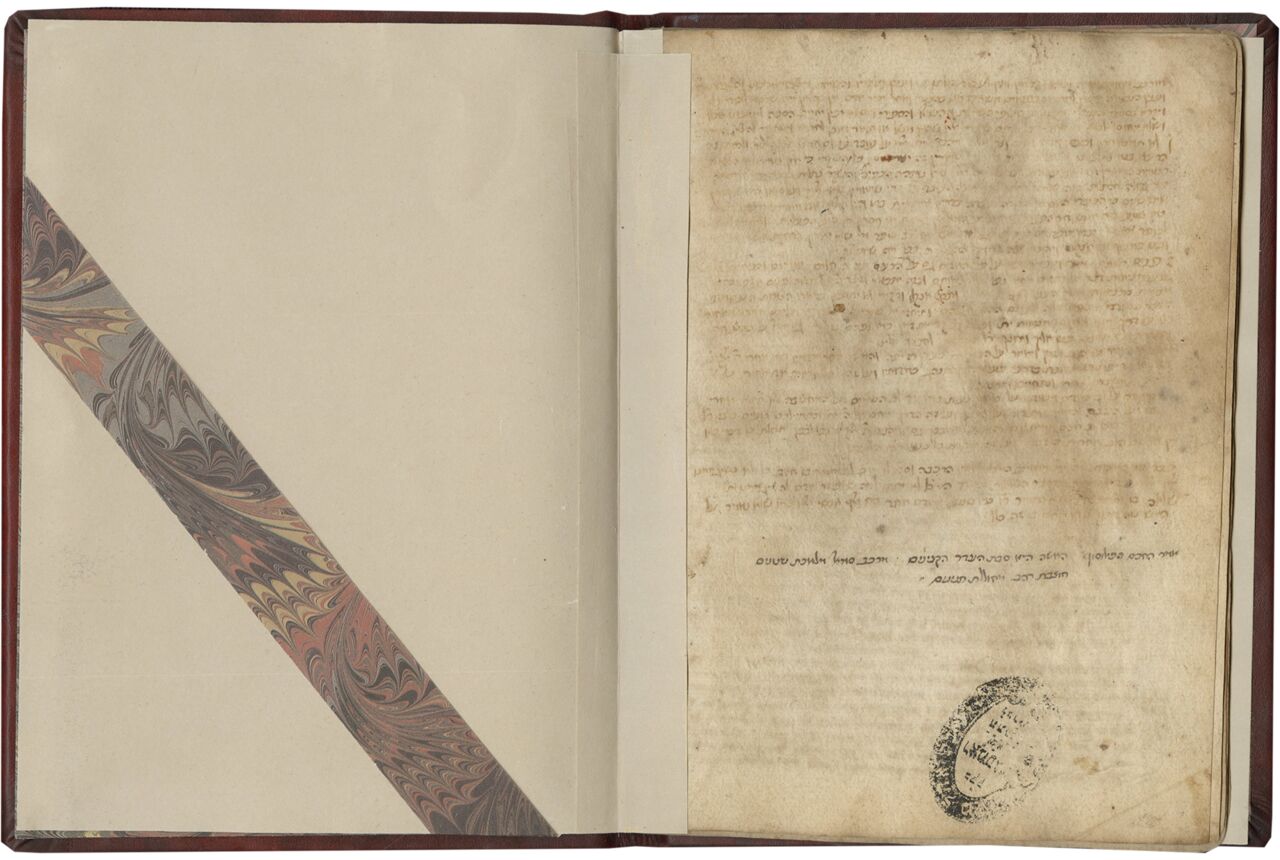

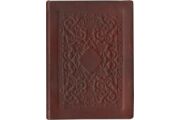

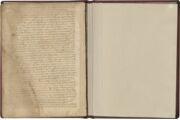

i + 11 + i folios on paper (similar to Briquet 2488, “balance,” Treviso, 1467-1468), modern marbled paper pastedowns and flyleaves, modern foliation in pencil in Arabic numerals in upper-outer corner of rectos, complete (collation i6 [-1 through 4 removed along with the first portions of the codex, see Provenance below] ii4 iii6 (-6 [presumably blank] removed), horizontal catchwords on ff. 6v, 7v, 9v, ruled in blind (justification approximately 160-165 x 105 mm.), single-column text written in an elegant Italian Ashkenazic semi-cursive script in brown ink in 43-57 lines, enlarged incipits, Tetragrammaton abbreviated to the letter he followed by an apostrophe, justification via insertion of space fillers, abbreviation, use of anticipatory letters, and dilation and contraction of final letters, episodic marginalia (sometimes partially cropped) and corrections in primary and secondary hands, Montefiore library stamp impression on f. 11v, slight scattered staining, dampstaining throughout, obscuring text on ff. 1, 8-11v, ff. 3-6, 9-10 loose. Modern blind-tooled maroon leather over pasteboard, very slightly scuffed, upper board entirely detached from text block. Dimensions 183 x 134 mm.

Drawn to the study of philosophy, especially that of Maimonides, late medieval Italian Jews compiled collections of texts that would facilitate their understanding of his works. The present such miscellany contains one of two known copies of Ruah hen currently held privately, as well as the only known copy of Sefer ben porat currently held privately. The latter treatise has yet to be printed. One of the Halberstam-Montefiore codices, this manuscript comes with sterling provenance.

Provenance

1. The colophon on f. 7v reads: “I have completed Ruah hen; praised be He Who discerns man’s thoughts… 47 days into the count [from Passover to Pentecost] in the year [5]228 [May 24, 1468],” with the signature of the scribe between “thoughts” and “47” deleted. More than a century ago, Solomon Joachim Halberstam (1890) identified the scribe as Isaiah ben Jacob Alluf da Gerona of Masserano, a prolific copyist active mostly in Mantua in the latter half of the fifteenth century, and subsequent scholarship has confirmed that identification (Freimann, 1950 and Sotheby’s, 2004). Indeed, the name Isaiah is enlarged where it appears in the text of Sefer ben porat on ff. 7v, 8v, telegraphing the scribe’s identity. Da Gerona signed a grammatical miscellany (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, MS Or. Qu. 647) in Trino, Northern Italy, on Thursday night, 29 Tammuz [5]230 (June 28, 1470), before completing two different works (both part of Frankfurt am Main, Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg, MS Oct. 5) a bit less than a month later, Tuesday, 26 Av [5]230 (July 24, 1470), in Mantua. He must eventually have returned to Trino, for a second colophon on f. 10 of our manuscript reads: “May it be [His] will that just as I merited to write it, so may I merit to arrive at a true, correct understanding of it that follows the clear path without straying from the straight line, amen. I began this on Sunday, finished it the next night, and wrote it for myself. It was completed 9 Tevet [5]231 [December 2, 1470], here, in Trino,” with da Gerona’s signature on the following line again deleted. It is not clear why there is an approximately two-and-a-half year gap between Ruah hen (f. 7v) and Sefer ben porat (f. 10), especially given that the aforementioned Berlin and Frankfurt manuscripts also seem to have been produced “for myself.” Relatedly, it is possible, given the passage of time and the itinerancy of the scribe, that Ruah hen was not written in Trino but elsewhere, perhaps Mantua.

This manuscript was once part of a larger volume comprising 65 folios (including two flyleaves at the fore), whose original collation was: i4 ii8 iii2 iv-vi12 vii6 viii4 ix6 (-6 [presumably blank] removed); our manuscript consists of quires seven (lacking the first four leaves), eight, and nine. The front flyleaves, apparently now lost, had preserved two Italian owners’ names: Marco di Dona Luzzatto(?) and a certain Samuel.

2. The manuscript eventually came into the possession of Halberstam (1832-1900), a wealthy Polish Jewish scholar and bibliophile. Halberstam inscribed the manuscript’s shelf mark (117) in pen on the first front flyleaf and provided a brief overview of its contents when he printed the catalog of his collection in 1890.

3. The Judith Lady Montefiore College in Ramsgate, England, purchased 412 manuscripts from Halberstam’s collection, including the present one. The transaction was carried out by Rabbi Moses Gaster (1856-1939), principal of the college between 1891 and 1896. The larger codex contains the library stamp of the institution, known in Hebrew as Yeshivat Ohel Mosheh vi-Yehudit, on its first and final folios (see now TM 1254, formerly on this site, now sold and in our archives, f. 1, and our manuscript, f. 11v). According to Sotheby’s (2008), its limp vellum binding also featured the Montefiore shelf mark (266).

4. Between 1898 and 2001, most of the Montefiore manuscripts, including ours, were placed on permanent loan at Jews’ College in London. In 2001, they were returned to the Montefiore Endowment Committee.

5. The full volume was sold at Sotheby’s New York on October 27, 2004 (lot 223). It was offered again four years later at Sotheby’s London on July 8, 2008 (lot 19), and at Kestenbaum & Company on December 18, 2008 (lot 313), both times without result. It has since been split into three parts–ff. 1-26 comprising TM 1254, ff. 27-52 comprising TM 1269, and ff. 53-63 comprising our manuscript–and each has been rebound and separately.

Text

ff. 1-7v, [Ruah hen], incipit, “amar ha-mehabber ruah hen… ki ein zeh yahas amitti ki be-histallek ha-gashmut me-itto yitbarekh yistallek ha-yahas beino u-bein ha-makom,” [followed by the scribe’s colophon (see Provenance above)];

ff. 7v-10, [Rabbi Judah ben Moses Romano’s Sefer ben porat], incipit, “yesod ha-yesodot ve-ammud ha-hokhmot leida she-yesh sham matsui rishon kavvanat mosheh ha-ne’eman be-beit ha-hokhmah hi… lo yitstarekhu yoter bei’u[r] mi-zeh ha-ma’amar ad aharito ha-hod ha-amitti yishpa aleinu me-hod yif‘ato ve-neheneh mi-ziv shekhinato ve-nagilah ve-nismehah bi-yeshu‘ato,” [followed by the scribe’s colophon (see Provenance above)];

ff. 10v-11v, [Short philosophical definitions and extracts], incipit, “tselem she-kol to’ar tsurat ha-davar kemo bi-mehugah yeta’arehu… amar he-hakham ha-pilosof ha-ishah hi sibbat he‘der ha-kinyanim merkav samma’el melekhet satanim hotsevet rahav meholelet tanninim.”

After having completed his Jewish legal magnum opus, the Mishneh torah, Rabbi Moses Maimonides (also known as Rambam; 1138-1204), spiritual leader of Egyptian Jewry, turned his attention to the difficulty faced by rationalistically inclined Jews in trying to integrate their faith with Aristotelian philosophy. The final result was Dalālat al-ḥāʼirīn (lit., The Instruction of the Perplexed), a landmark in the history of Jewish thought that, with its treatment of such topics as anthropomorphism, prophecy, Providence, cosmogony, ethics, and political science, has exerted enormous influence on both Jews and Gentiles from the Middle Ages down to the present day. As with most of Maimonides’ compositions, the book was originally written in Judeo-Arabic but was quickly translated into Hebrew, in this case by Rabbi Samuel Ibn Tibbon (c. 1150-c. 1230) and, separately, by Rabbi Judah al-Harizi (1165-1225). While the Judeo-Arabic version continued to circulate, especially among Mizrahi and Yemenite Jewry, most European Jews knew it only in its Hebrew recensions, both titled Moreh ha-nevukhim (lit., The Guide for the Perplexed).

Jews living in medieval and Renaissance Italy evinced significant interest in philosophical and scientific study à la Maimonides, whose various works have come down to us in numerous Italian copies. Indeed, when Hebrew printing with movable type began in Italy c. 1469, Moreh ha-nevukhim was among the first books published (Rome, c. 1474). The present philosophical miscellany comprises three distinct works, all of which relate in some way to Rambam’s thought.

The first, entitled Ruah hen (A Spirit of Grace), takes its name from its opening words: “Says the author: A spirit of grace [Zech. 12:10] from the esteemed treatise Moreh ha-nevukhim passed me by [Job 4:15].” The anonymous author goes on to explain that his encounter with Maimonides’ writing “drew back the veil from my thoughts and enlightened my eyes,” inducing him to seek greater understanding “from teachers and books.” The results of his research were organized into eleven chapters that, collectively, constitute a kind of concise introduction to medieval science and philosophy, with special relevance for those interested in studying Moreh ha-nevukhim and other theological-philosophical tracts. The subjects covered include: the entities in the universe and their relationships (chap. 1); Aristotelian psychology (chaps. 2-5); the types of knowledge that cannot be demonstrated (chap. 6); theories of the simple bodies, vapors, clouds, and the stratification of fire and air (chap. 7); matter, form, privation, and the types of composition of corporeal bodies (chaps. 8-9); as well as the theory of the Aristotelian categories and the possibility of change within those categories (chaps. 10-11). Through this book, readers became acquainted with the thought of Neoplatonists like Alpharabius and Avicenna and were given a brief overview of topics like logic, meteorology, physics, and metaphysics.

Ruah hen was probably composed in Provence (or Italy) between 1210 and 1250. Its Hebrew terminology is highly reminiscent of that used by the Ibn Tibbon family, which may explain why it has been variously attributed to Rabbis Judah Ibn Tibbon (c. 1120-1190), his son Samuel (the aforementioned translator of Dalālat al-ḥāʼirīn), and the latter’s son Moses (fl. 1244-1283). (More likely is that it was compiled by someone named Anatoli, perhaps Rabbi Jacob Anatoli [c. 1194-1256], who married into the Ibn Tibbon family.) The work’s mode of presentation is simple, clear, and accessible, which helped it achieve the status of a scientific bestseller that has survived in over 110 manuscript copies ranging in date from 1272 to 1896. The book was also printed at least sixteen times for Jewish audiences between 1544 and 1931 and was even translated early on into Latin by a Jewish convert to Christianity (Cologne, 1555). At least sixteen (and perhaps as many as forty-eight) of the extant manuscripts—including the five earliest dated—as well as the first three printed editions, were produced in Italy, testifying to Ruah hen’s popularity there. Ofer Elior has studied the work extensively (2010, 2022) and also produced the only modern critical edition (2016).

The second tract represented here is Sefer ben porat, a commentary on the first four chapters (through 4:9) of Rambam’s Hilkhot yesodei ha-torah, a treatise on the fundamentals of Jewish faith situated at the beginning of the Mishneh torah. These chapters treat religious commandments that are purely intellectual in nature: to know that there is a God, to not think that there is any other god, to recognize God’s unity, to love God, and to fear God. They also cover topics in physics and metaphysics, providing a useful springboard for explorations of Aristotelian philosophy more generally (Rothschild, 2004). The commentary’s author was Rabbi Judah (Leone) ben Moses Romano, one of the primary expositors of Maimonidean philosophy in fourteenth-century Italy. His oeuvre includes, besides the present work, Hebrew translations of Latin Scholastic literature, as well as a philosophical commentary on the Creation story in Genesis, a Judeo-Italian glossary of philosophical terms, and a treatise on prophecy (Sirat, 1996). Sefer ben porat survives in about twenty-nine complete or partial copies from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries, about two-thirds of them written in Italy and/or in Italian hands, some accompanied by the comments of a certain Moses ben Shabbetai. The text has never been edited.

The final, brief work contains definitions of several metaphysical terms in the style of Moreh ha-nevukhim I:6ff., followed by philosophical discussions in at least seven numbered sections. Its authorship and origins remain a mystery, and it is not known whether any other surviving manuscripts contain this text.

Literature

Elior, Ofer. “‘Ruah hen’ ke-aspaklaryah me’irah: limmud ha-madda be-tarbuyyot yehudiyyot shonot kefi she-hu mishtakkef be-mavo beinaimi la-madda ha-aristotali u-bikkorotav le-orekh ha-dorot,” PhD diss., Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, 2010.

Elior, Ofer. Ruah hen yahalof al panai: yehudim, madda u-keri’ah 1210-1896, esp. pp. 92-93, 105-106, 122 n. 112, Jerusalem, 2016.

Elior, Ofer. “Ruaḥ Ḥen: An Early Popular Hebrew Introduction to Science,” in The Popularization of Philosophy in Medieval Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, ed. by Marieke Abram, Steven Harvey, and Lukas Muehlethaler, pp. 173-183, Turnhout, 2022.

Engel, Edna. “Immigrant Scribes’ Handwriting in Northern Italy from the Late Thirteenth to the Mid-Sixteenth Century: Sephardi and Ashkenazi Attitudes toward the Italian Script,” in The Late Medieval Hebrew Book in the Western Mediterranean: Hebrew Manuscripts and Incunabula in Context, ed. by Javier del Barco, pp. 28-45, at pp. 38-40, Leiden and Boston, 2015.

Freimann, Aaron. “Jewish Scribes in Medieval Italy,” in Alexander Marx Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday, ed. by Saul Lieberman, pp. 231-342 (English section), at pp. 276-278 (no. 204), New York, 1950.

Halberstam, Solomon Joachim. Kohelet shelomoh, pp. 14, 135, 143-144 (no. 117), Vienna, 1890.

Hirschfeld, Hartwig. Descriptive Catalogue of the Hebrew MSS. of the Montefiore Library, p. 86 (no. 266), London and New York, 1904.

Levanon, Ariel. “Hebbetim hevratiyyim ve-tarbutiyyim be-ha‘atakat sefarim ivriyyim be-italyah bi-tekufat ha-renesans,” Yad la-kore 28:3-4 (November 1994), pp. 14-19.

Rothschild, Jean-Pierre. “L’enseignement de la philosophie de Maïmonide selon le Sefer ben porat de R. Juda Romano (Italie, XIVe siècle),” in Maïmonide: philosophe et savant (1138-1204), ed. by Tony Lévy and Roshdi Rashed, pp. 433-462, Leuven, 2004.

Sirat, Colette. “Le livre ‘Rouaḥ Ḥen’,” Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies 3:C (1973), pp. 117-123.

Sirat, Colette. A History of Jewish Philosophy in the Middle Ages, pp. 269-271, Cambridge and Paris, 1996.

Zwiep, Irene E. “Did Maimonides Write Nonsense? Intellect, Sense and Sensibility in Ruach Chen,” in Unless some one guides me… Festschrift for Karel A. Deurloo, ed. by J.W. Dyk et al., pp. 363-367, Maastricht, 2001.

Online Resources

Our MS

https://www.nli.org.il/he/manuscripts/NNL_ALEPH990000651550205171/NLI#$FL29814007

TM 1254

https://www.textmanuscripts.com/medieval/mivhar-ha-peninim-choice-of-pearls-205576

Sotheby’s New York sale, October 27, 2004 (lot 223)

https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2004/important-hebrew-manuscripts-from-the-montefiore-endowment-n08040/lot.223.html

Sotheby’s London sale, July 8, 2008 (lot 19)

https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2008/western-oriental-manuscripts-l08240/lot.19.html

Kestenbaum & Company sale, December 18, 2008 (lot 313)

https://www.kestenbaum.net/auction/lot/auction-42/042-313/

Venice, 1544 edition of Ruah hen

https://www.nli.org.il/he/books/NNL_ALEPH990040987410205171/NLI

Venice, 1549 edition

https://www.hebrewbooks.org/45172

Cologne, 1555 edition

https://www.nli.org.il/he/books/NNL_ALEPH990013027050205171/NLI

Cremona, 1566 edition

https://www.nli.org.il/he/books/NNL_ALEPH990010884310205171/NLI

TM 1268