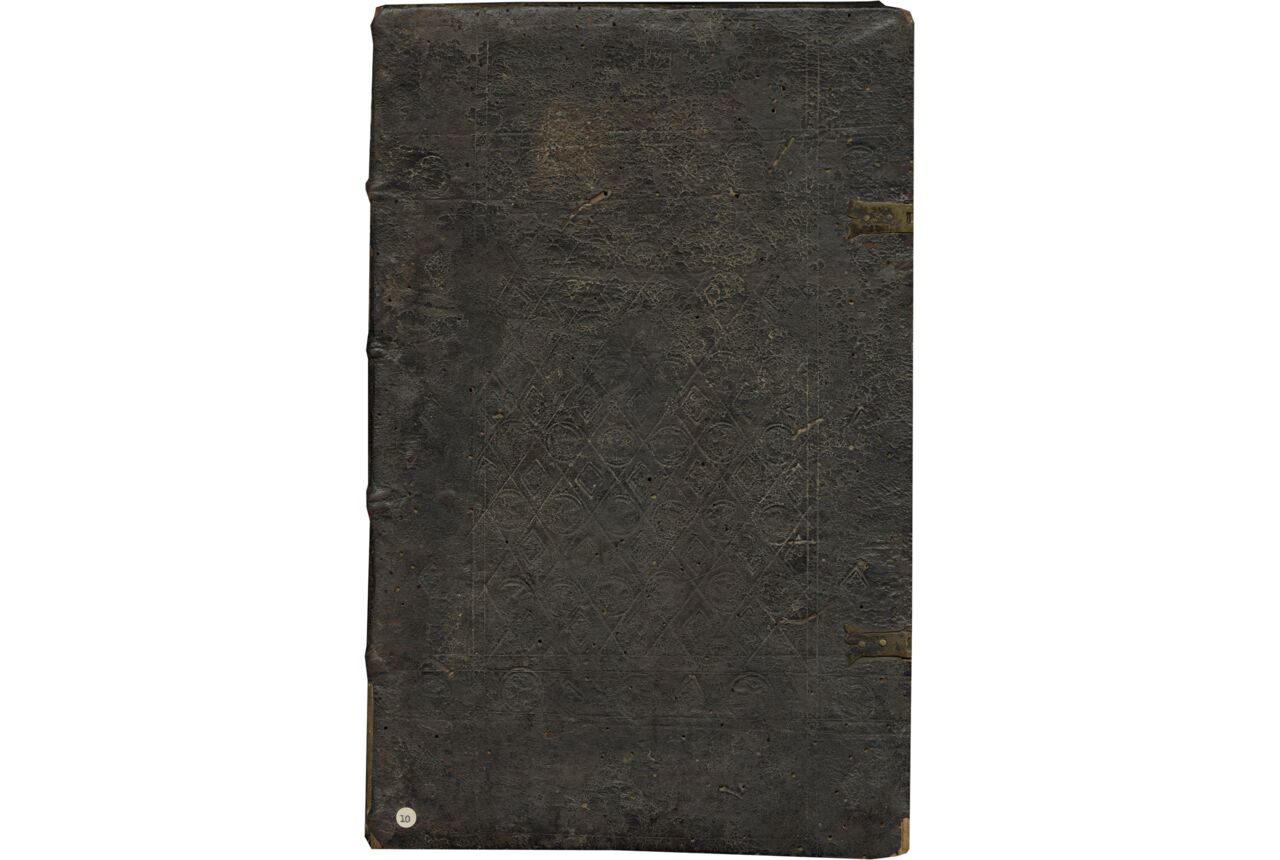

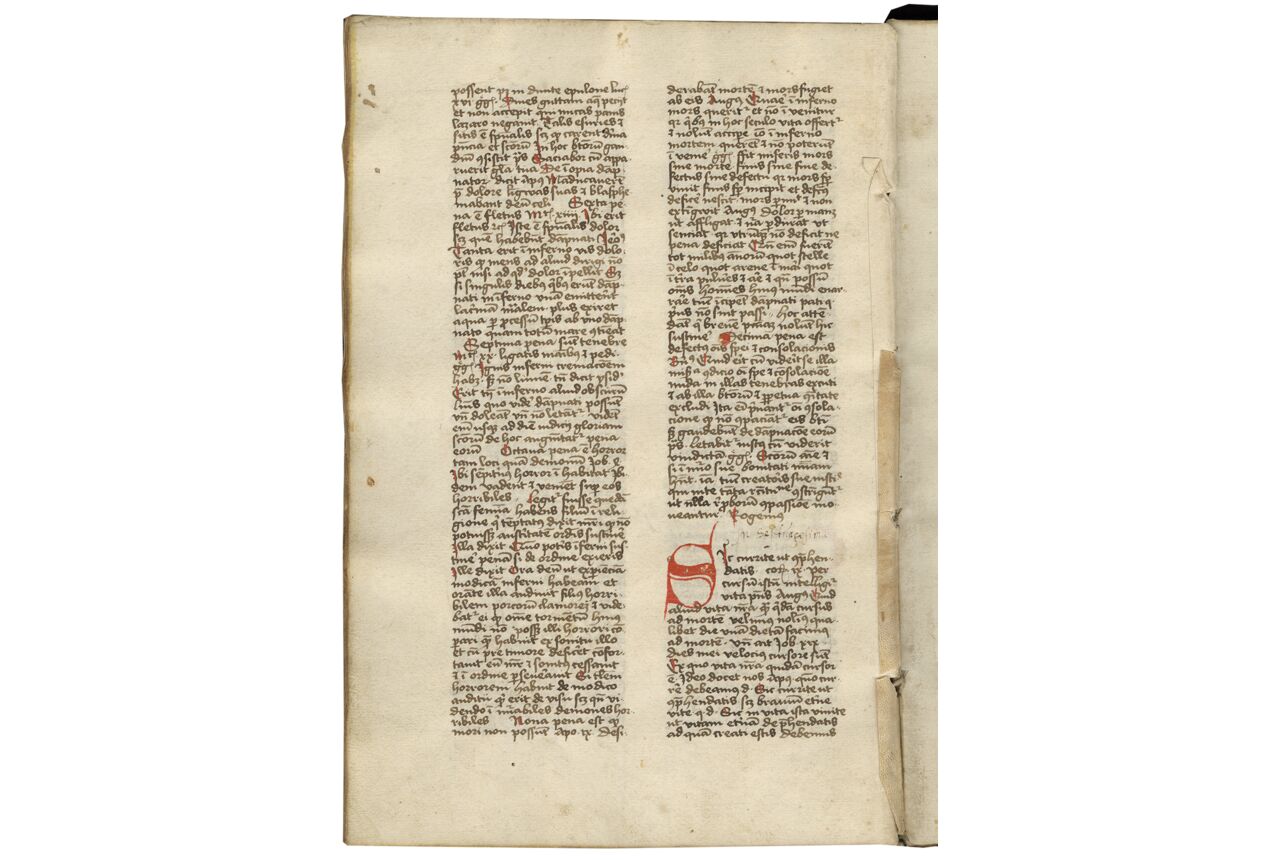

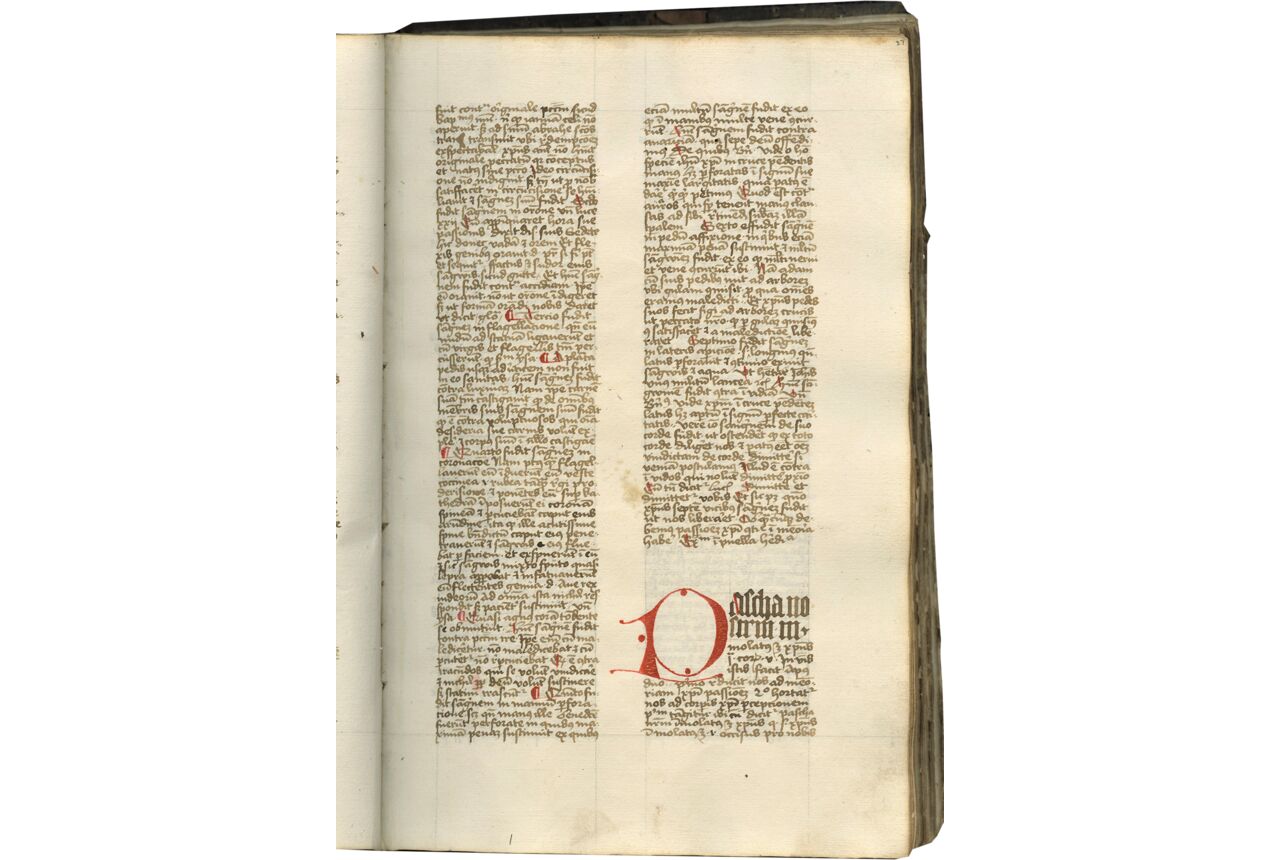

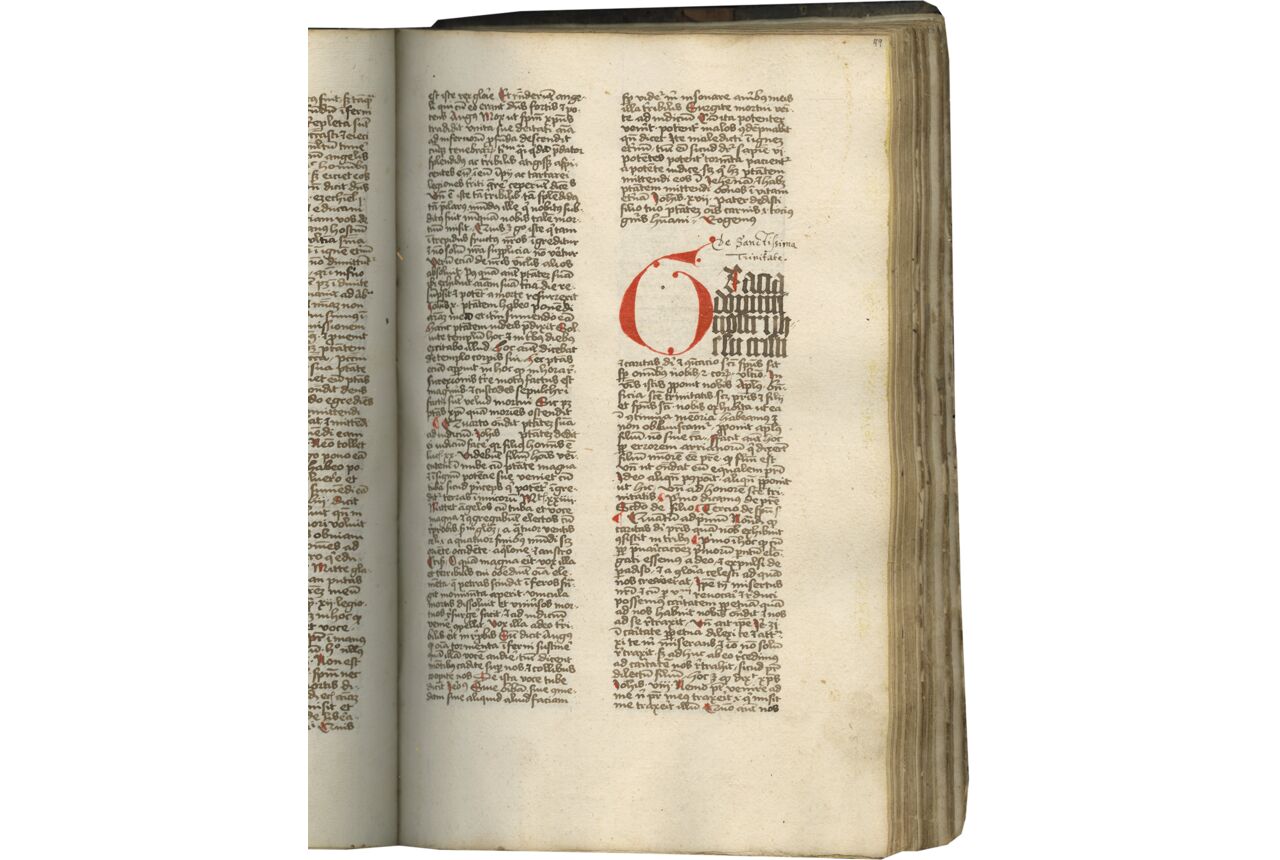

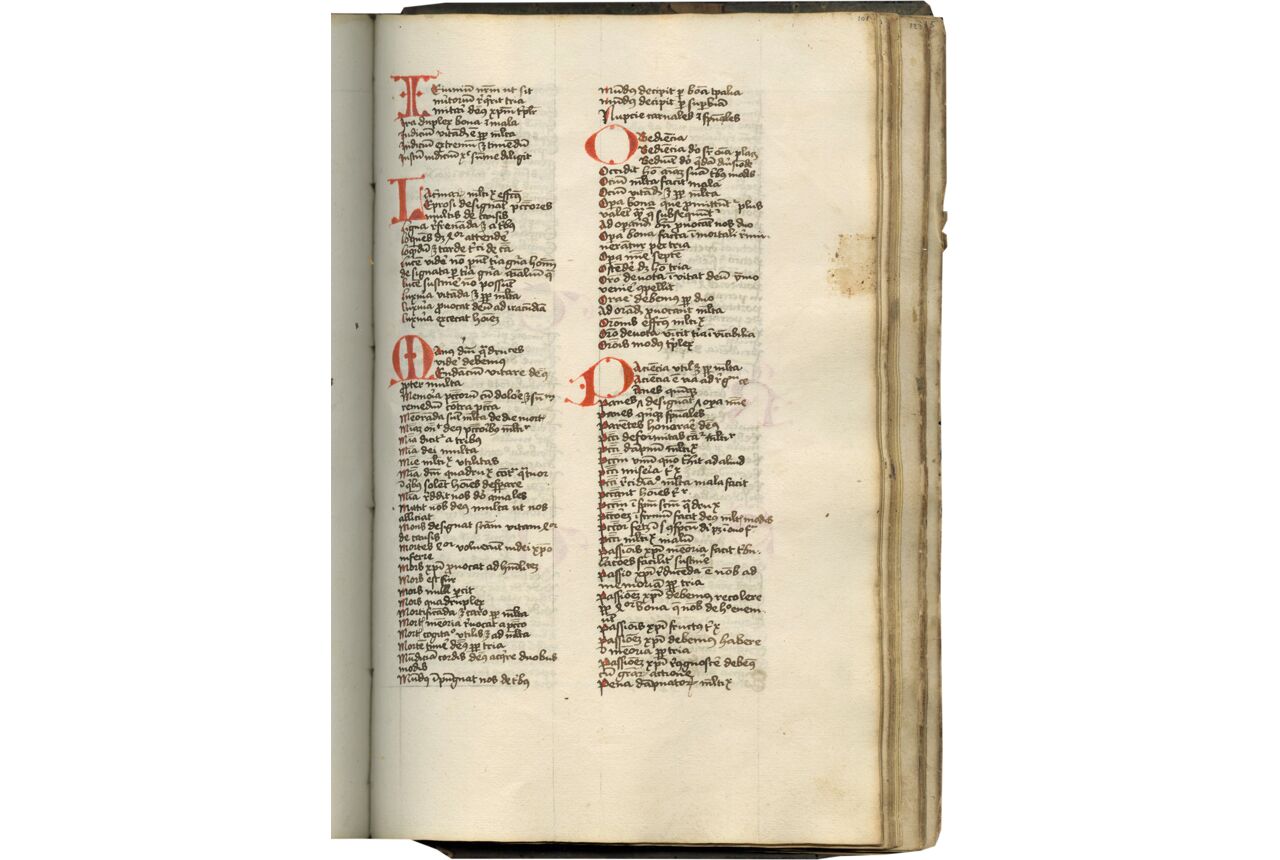

141 folios on paper, two watermarks: a bull’s head with eyes, ears, and curved horns surmounted with a rod topped with a [6-8?] petalled flower, similar to Briquet no. 14763 (Rietenburg, 1472), Piccard nos. 65693 (Würzburg, 1473), 64727 (s. loc., 1470), 64783 (s. loc., 1467), 65656 (Braunschweig, 1466), 65657 (Wallerstein, 1466), and a Latin cross extending from a [crown? pedestal? mountain?], unidentified in Briquet or Piccard, modern foliation in pencil in Arabic numerals upper fore-edge recto, 1-141, apparently complete (collation i-x12 xi4 [-3, 4 after f. 122, likely cancelled blanks] xii12 xiii12 [-8, 9, 10, 11, 12, after f. 141, likely cancelled blanks]), each quire supported with a parchment guard strip, horizontal catchwords quires iii-v and vii-viii, frame ruled in plummet (justification Part I, ff. 1-122v, 227-245 x 137-147 mm.; Part II, ff. 123-141, 235 x 145 mm.), copied in two main Gothic bookhands, in Part I, a cursiva recentior written below top line with occasional headings in Gothic textualis (at ff. 1, 27, 40v, 49, 95v), and in Part II in a semi-hybrida written below top line, with a 14-line addition at f. 102 in a slightly later Gothic bookhand (cursiva recentior), Parts I and II both in two columns of 57-63 lines, in black or dark brown ink with majuscules heightened by strokes of red, Part II also with sublineation in red, 157 initials of 3-5 lines in plain red ink with black ink guide letters visible, space left for initial at f. 140, very occasional scribal corrections, occasional annotations in Latin in dark brown, black, or pale red ink in an early modern hand, typically identifying individual sermons, manicules in green at f. 87, a few wormholes and some staining throughout, early parchment and paper repairs to support at f. 40 with no loss of text, overall in very good condition. EARLY BINDING of dark brown, blind-stamped leather over wooden boards, spine with four raised bands, once fastened back to front (two brass catches, upper board, and brass clasp with remnants of leather strap, lower board, second clasp now lost, upper board detached, revealing slots for tawed cords along with five parchment fragments recycled from an older manuscript, otherwise in good condition. Dimensions 330 × 220 mm.

Still largely unedited and understudied, sermons have been called the “central literary genre in the lives of medieval European Christians and Jews.” The “Paratus Sermons” in this large handsome manuscript from the collection of Sir Thomas Phillipps are signed and dated in a detailed colophon and survive in an early blind-stamped binding. These very brief sermons include biblical verses and, notably, exempla, and focus on elementary catechistic issues, making them very popular with preachers who used them to formulate full sermons. Like so many sermon collections, it is unedited, as are the otherwise unknown sermons appended to it, also created in a Dominican milieu.

Provenance

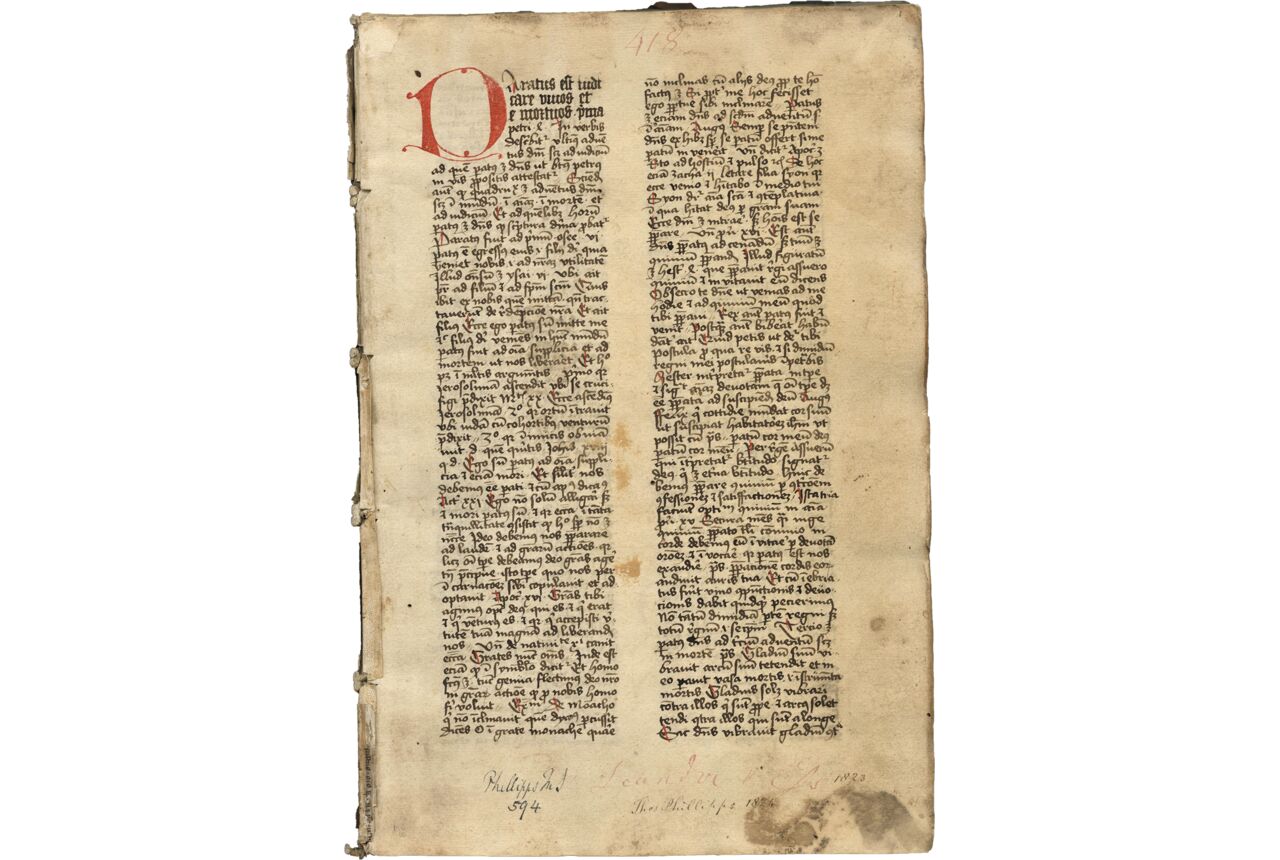

1. Copied in Germany by Albertus Carpentarius, O.P., and dated 6 o’clock on the Saturday before the Feast of St Margaret, in 1472 (i.e., 18 July, Margaret’s Feast falling on Monday 20 July in the latter year); colophon: “Finitum et completum est hoc opus per manus fratris Alberti carpentarij ordinis fratrum predicatorum. Sub anno domini m° cc°cc° lxx·ij· Sabbato ante festum margarete virginis et maartiris hora vj ante prandium …” (f. 100). Albert has not been identified in other sources (not listed in Benedictins de Bouveret; Watermark evidence, although not conclusive, perhaps points to Southern Germany.

2. Fifteenth- or sixteenth-century inscription in German, in black ink, back pastedown, “… von der <M?rler> alle da<?> voller.”

3. Belonged to Leander van Ess (1772-1847), the German Catholic theologian and bibliophile; inscription, “Leander van Ess” (f. 1, bas de page), with his number “418” (f. 1, upper margin), both in faded red ink; no. 418 = no. 210 in his catalogue (Van Ess, 1823, p. 37).

4. Belonged to the famous bibliophile and insatiable collector, Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872); 19th-century inscription, “Thomas Phillipps 1824,” in brown ink, the same hand adding “1823” next to van Ess inscription (f. 1); his 19th-century cataloguing number: “Phillipps MS 594,” in black ink (f. 1), and his bookstamp: “Sir T.P. Middle Hill” above A Lion rampant, with annotation “596” struck out and emended, in pencil and black ink, to “594” (f. 141).

5. Purchased by Dobell at Phillipps sale, Sotheby and co., June 6, 1910, lot 267.

6. Sotheby’s, December 17, 1940, Lot 20; purchased by Maggs.

7. Late 19th-21st century annotations, in pencil, back pastedown: “<PC 10>” (f. 1); “loso” (or ”leso”?); “S . 12 40” (or “5 . 12 46”?).

8. Purchased from Maggs, 1944, by Marvin L. Colker (1927-2020), becoming Colker MS 10 (Faye and Bond, 1962, p. 517; and Bibale, “Fonds de la librairie Maggs”); small, round, white sticker bearing typescript numeral “10,” lower left corner front cover. Colker was Professor of Classics at the University of Virginia and a renowned paleographer, who catalogued the manuscripts at Trinity College Library, Dublin, and who assembled an impressive collection of medieval material.

Text

ff. 1-100, incipit, “Paratus est iudicare vivos et mortuos prima petri 4[:5], In verbis describitur ultimus adventus domini scilicet ad judicium ad quem paratus est dominus ut beatus petrus … qui narrat stulto sapientiam. Roge[mus dominum nostrum Iesum Christum]; … [final sermon], incipit, “Templum dei sanctum est quod estis vos cor .3 [1 Corinthians 3:17], Karissimi iocunda est deo et accepta huius nostri materialis templi dedicationis … Sedebit populus meus in pulchritudine pacis in tabernaculis fiduciae et in requie opulenta ad quam nos perducat amen”; [scribal colophon], Ffinitum et completum est hoc opus per manus fratris alberti carpentarii ordinis fratrum predicatorum. Sub anno domini mo CCCCo lccii sabbato ante festum margarete virginis et martiris hora vi ante prandium de quo laudet deus et pia mater eius, [added later: Amen].

‘Parati’ Sermones de tempore, from Advent Sunday to the 25th Sunday after Pentecost (Schneyer, 1972, pp. 523-537), deviating from Schneyer’s order and with over a dozen that we were not able to identify in Schneyer, thus: Schneyer sermon nos. 1 (ff. 1-2), 2 (f. 2), 5 (ff. 2-3), 11 (ff. 3-4), 12 (f. 4), 14 (ff. 4-5), 9 (f. 5-5v), 17 (ff. 5v-6), 20 (f. 6-6v), 23 (ff. 6v-7), 24 (f. 7-7v), 26 (f. 7v), 27 (ff. 7v-8v), 32 (ff. 8v-9), 33 (ff. 9-10), 35 (f. 10-10v), 41 (ff. 10v-11), 42 (f. 11-11v), 45 (ff. 11v-12), 49 (f. 12-12v), 50 (ff. 12v-13v), 52 (ff. 13v-14), 53 (f. 14-14v), 56 (ff. 14v-15), 58 (ff. 15-16), 61 (f. 16-16v), not found (ff. 16v-17), 66 (f. 17-17v), 57 (ff. 17v-18), 60 (ff. 18-19), 72 (ff. 19-20), 74 (f. 20-20v), not found (ff. 20v-21), not found (ff. 21-22), 76 (ff. 22-23), not found (ff. 23-24), 81 (ff. 24-25), 84 (f. 25-25v), not found (ff. 25v-26), not found (f. 26-26v), not found (ff. 26v-27), 92 (ff. 27-28v), 94 (ff. 28v-29), 95 (ff. 29v-30), 96 (ff. 30-31), 97 (f. 31-31v), 98 (ff. 31v-32v), 99 (ff. 32v-33), 100 (f. 33-33v), 101 (f. 34-34v), 102 (ff. 34v-35), 103 (ff. 35-36), 104 (ff. 36-37), 105 (f. 37-37v), 106 (ff. 37v-38), 107 (f. 38-38v), 108 (ff. 38v-39v), 109 (ff. 39v-40), 110 (f. 40-40v), 111 (ff. 40v-41v), 112 (ff. 41v-42), 114 (ff. 42-43), 115 (f. 43-43v), 116 (ff. 43v-44v), 117 (ff. 44v-45), 119 (ff. 45-46v), 118 (ff. 46v-47v), not found (ff. 47v-48), 121 (ff. 48-49), 122 (ff. 49-50), 123 (ff. 50-51v), 124 (ff. 51v-52), 125 (ff. 52-53), 126 (f. 53-53v), 127 (ff. 53v-54v), 128 (ff. 54v-55), 129 (f. 55-55v), 130 (ff. 55v-56v), 131 (ff. 56v-57), 132 (ff. 57v-58), 133 (ff. 58-59), 134 (f. 59-59v), 135 (ff. 59v-60v), 136 (ff. 60v-61), 137 (ff. 61-62), 138 (f. 62-62v), 139 (ff. 62v-63v), 140 (ff. 63v-64v), 141 (ff. 64v-65), 142 (ff. 65-66), 143 (f. 66-66v), 144 (ff. 66v-67v), 145 (ff. 67v-68v), not found (ff. 68v-70), 146 (ff. 70-71), 147 (ff. 71-72), 148 (ff. 72-73), 149 (ff. 73v-74), 150 (ff. 74-75), 151 (ff. 75-76), 152 (f. 76-76v), 153 (ff. 76v-77v), 154 (ff. 77v-78v), 155 (ff. 78v-79v), 156 (ff. 79v-80v), 157 (ff. 80v-81), 158 (ff. 81-82), 159 (f. 82-82v), 160 (ff. 82v-83v), 161 (ff. 83v-84), 162 (ff. 84-85), 163 (ff. 85-86), 164 (f. 86-86v), 165 (ff. 86v-87v), 166 (ff. 87v-89), 167 (f. 89-89v), 168 (ff. 89v-90), 169 (ff. 90v-91v), 170 (ff. 91v-92v), not found (ff. 92v-93v), 172 (ff. 93v-94v), 173 (ff. 94v-95v), not found (ff. 95v-96v), not found (ff. 96v-98), not found (f. 98-98v), not found (ff. 98v-100).

The sermon for the Dedication of a Church on ff. 98v-100 is not one of the sermons for this feast recorded in Schneyer (see his description of the Sanctoral).

ff. 100-102, incipit, “Adventus dominum quadruplex <divinitus ad indicium> diversitatum utilitates … ysaac et ysmahel condiciones”;

Alphabetical index of Christian terms, possibly a subject index.

f. 102, incipit, “Sermo de dedicatione. Item sermo de animabus … Passio domini nostri ihesu christi”;

Short list of sermon topics added in another hand.

ff. 102v-106, Sermo de circumcisione domini pro novo anno, incipit, “Apparuit benignitas et humanitas salvatoris nostri ad titum 3° [Titus 3], pro introductionem occurrit in doctor mellifluus Bernardus … ihesum christi vitam finiamus Qui cum patre et spiritus vivit et regnat”;

Unknown added sermon, not identified in Schneyer.

ff. 106v-108v, incipit, “SI inveni gratiam in oculis tuis accipe munusculum hoc de mani mea [Genesis 33:10], … partem receperit pro novo anno devocationis gratiam sentiet pater ante mariae filio qui cum etc.”;

Unknown added sermon, not identified in Schneyer.

ff. 109-122v, Sermo de circumcisione domini pro novo anno, incipit, “Innduimini dominum ihesum christum. Romanos 3 [Romans 13:14] lex antiquorum regum que fuisse dinoscitur ut ullus ante eos accederet pro aliqua gracia petenda … non audeo loqui aliquid quae per me non efficit christus ad quam gloriam nos <pro> domine ihesus christus; … [final sermon], incipit, “Pacem habentes non vos met ipsos defendentes sed date locum ire. Ro. 12 [Romans 12:18-19] … in sollertie punitiva cum concluditur mihi vindictam”;

Sermons attributed to Nicolaus Asculanus, O.P. (fl. 1321-1342) (Schneyer, 1972, pp. 205-215, sermons nos. 2, 4, 6, 8-9, 11, 13, 15, 17); no edition known.

ff. 123-139v, incipit, “QUo abiit delectus [sic.] tuus o pulcherrima mulierum Quo declinavit dilectus tuus et quaeremus eum tecum Canticorum v° [Song of Songs 5:17] … Prestante ordinis domino nostro ihesu Christo cum patre et spiritu sancto benedicto. In secula seculorum amen”;

Unknown added sermon; not identified in Schneyer.

ff. 140-141, incipit, “[S]I fuerit minister iustus computo <eum [recte: illum(?)] cum> paulo qui gloriam suam non <quasunt [recte: quaerunt(?)]> Ego plantaui appollo rigavit deus <[incert.]> incrementum dedit Qui vero superbus fuerit minister cum zabulo computatur … Puerorum israhel dilexi eum et cetera”;

Excerpts from Holkot, Commentarius in Librum Sapientiæ, lectio 119, cc. 02, 04-10; printed: Lyons, 1498; Basel, 1506; Paris, 1518; Basel, 1568; and later editions; electronic edition: Scholastic Commentaries and Texts Archive (Holcot, Commentarius).

Thousands of sermon manuscripts survive from the Middle Ages, and yet many (or even most) of them are unedited, and the genre remains understudied. In a largely oral culture, the sermon was one of the main means of communication to such an extent that Beverly Kienzle has called it “the central literary genre in the lives of medieval Christians and Jews.” They are transmitted in many different types of manuscripts: sermons that were actually preached, collections of notes taken by a listener to a sermon, personal collections of a preacher, and model sermons, among many others. The “Paratus Sermons” (Sermones ‘Parati’ de tempore et de sanctis) that constitute the bulk of the present collection are related to model sermons, and provide material for preachers to compose longer, complete sermons. Many of them focus on basic catechistic issues such as the Ten Commandments and the Sacraments; they begin with a biblical verse and include one or two exempla used to teach basic catechistic issues. They take their name from the opening words of the first sermon, Paratus est iudicare vivos et mortuos (from Peter 4:5: “Ready to judge the living and the dead”). For an excellent introduction to sermons see the Primer (I: Sermons) by Laura Light in Online resources.

The Sermones ‘Parati’ de tempore et de sanctis survive in at least twenty extant manuscript copies (Schneyer, 1972, p. 537; Roest and van der Heijden, 2019, s.v. “Bertholdus de Wiesbaden”). The collection still lacks a modern critical edition but was printed in two dozen incunable and later editions (Thayer, 2017, ch. 2); first printed in Cologne, c.1480, by Conrad Winters de Homborch (ISTC no. ip00091500). The author of these sermons remains unknown (Thayer, 2017, ch. 2; Glonar, 1918) but is a matter of ongoing debate. The nineteenth-century Trier catalogue lists them in Stadtbibliothek MS 283 as attributed to the Augustinian hermit Johannes de Gamundia or Gammundia (Keuffer, 1894, pp. 80-81; see also Deutsche National Bibliothek, “Johannes, de Gammundia”), but Zumkeller noted that the attribution was incorrect, instead suggesting that these sermons may be by the Franciscan Berthold von Wiesbaden, adding, however, that this attribution remains unproven (Zumkeller, 1962, pp. 82-83). Though repeated by Bert Roest (Roest, 2004), the von Wiesbaden attribution has been rejected by Stephen Mossman (2012, p. 259 n. 80).

Augmenting the foregoing is a smattering of additional sermons, some of which can be attributed to Nicolaus Asculanus, O.P. (fl. 1321-1342). A native of Ascoli Piceno, in Italy’s Marche region, Asculanus – alt. Nicolaus de Asculo / Esculo, Nicolutius / Nicolucius de Aesculo, Nicoluccius Iacobi – pursued studies in Bologna, where his presence is attested in 1321. Within the decade, he returned to the Marches as Prior of the Convent of Saint-Pierre-Martyr d’Ascoli (in 1330), subsequently (in 1342) holding the same office at the Convent of Saint-André de Faenza in Emilia-Romagna (Masson, 2009, p. 8). Said to have reestablished austerity of morals in Ascoli’ (“rétabli l’austérité des mœurs à Ascoli” (Masson, 2009, p. 8)), he authored a number of works including the sermons for the dead for which he is best known. Our codex includes excerpts from Asculanus’ Sermones de epistolis et evangeliis dominicalibus per annum, extant in roughly eighty manuscript witnesses (Schneyer, 1972, pp. 214-215; Bibliothèque nationale de France, “Nicolaus Asculanus”), and discussed in depth by Xavier Masson (2009), they, too, nonetheless unedited.

At the end of our manuscript is a slightly shortened version of lectio 119 from the Commentarius in Librum Sapientiæ of Robert Holcot or Holkot, O.P. (d. 1349). A commoner born in Holcot, Northampton, Holkot obtained a doctorate in theology from Oxford, then served as Dominican regent master at the same institution, before taking a position in London, as clerk to Richard of Bury, Bishop of Durham. At some juncture he may also have served as a Dominican regent master or lecturer in theology at Cambridge. Regardless, by 1343 he had returned home to Northampton’s Dominican priory where he died of plague six years later. An active scholar who lectured on Lombard and participated in debates, Holkot is best known for his lectures on the Book of Wisdom (Gelber and Slotemaker, 2021), excerpted here. They survive in “at least 175 manuscripts,” along with a dozen incunabular and early modern editions (Slotemaker and Witt, 2016, p. 306, n. 1).

Watermark, paleographical, and colophon evidence all align to place production of our manuscript in late fifteenth-century Germany, with extensive internal provenance clues attesting to the codex’s subsequent travels through several major collections, including that of the nineteenth-century English antiquarian and bibliophile, Sir Thomas Phillipps. The volume’s named scribe – “fratris Alberti carpentarij ordis fratrum predicatorum” (f. 100) – likely copied these widely-disseminated yet still unedited sermons with a view to his own use and consultation, or perhaps to assist his fellow preachers. Signs of engagement left by these earliest readers and their later counterparts point to the potential value of this collection as a source for historical religious practice.

Literature

Bénédictins du Bouveret. Colophons de manuscrits occidentaux des origines au XVIe siècle, Fribourg, 1965, v. 1.

Bond, W. H. and Faye, C. U. Supplement to the Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada, New York, 1962, p. 517, no. 10 (collection of Marvin Colker).

Glonar, J.A. “‘Paratus’ und ‘Meffreth’: Zwei Vermeintliche Autoren also Beispiele Bibliographischer Missverständnisse,” Zeitschrift für Bücherfreunde, new ser., 9/2, no. 8/9 (1918), pp. 233-234.

Holkot, Roberti. In Librum Sapientiae Magistri Roberti Holkot Eximii Theologiæ Professoris, Ordinis Fratrum Prædicatorum, Prælectiones. Basel, 1568.

Kienzle, Beverly and David d’Avray, “The Sermon,” Medieval Latin: An Introduction and Bibliographic Guide, ed. F.A.C. Mantello and A.G. Rigg, Washington D.C., 1996, pp. 659-669.

Keuffer, Max. Beschreibendes Verzeichnis der Handschriften der Stadtbibliothek zu Trier, Trier, 1894.

Masson, Xavier. Une Voix Dominicaine dans la Cité: Le Comportement Exemplaire du Chrétien dans l’Italie du Trecento d’après le Recueil de Sermons de Nicoluccio di Ascoli, Rennes, 2009.

Mossman, Stephen. “Preaching on St. Francis in Medieval Germany,” Franciscans and Preaching: Every Miracle from the Beginning of the World Came about through Words, ed. Timothy J. Johnson, Leiden, 2012, pp. 231-272.

The Phillipps Manuscripts. Catalogus librorum manuscriptorum in bibliotheca D. Thomae Phillipps, B.T. impressum typis Medio-Montanis 1837–1871, reprint with intro by A.N.L. Munby, London, 1968.

Roest, Bert. Franciscan Literature of Franciscan Instruction before the Council of Trent, Studies in the History of Christian Traditions 117, Leiden, 2004.

Schneyer, Johann Baptist. Repertorium der Lateinischen Sermones des Mittelalters: für die Zeit von 1150–1350, Heft 4 (Autoren: L–P), Beiträge zur Geschichte der Philosophie und Theologie des Mittelalters 43, Münster, 1972.

Schneyer, Johann Baptist. Repertorium der Lateinischen Sermones des Mittelalters: für die Zeit von 1150–1350, Heft 5 (Autoren: R–Schluß [W]), Beiträge zur Geschichte der Philosophie und Theologie des Mittelalters 43, Münster, 1974.

Slotemaker, John T., and Jeffrey C. Witt. Robert Holcot, Oxford, 2016.

Thayer, Anne T. Penitence, Preaching, and the Coming of the Reformation, St Andrew’s Studies in Reformation History, New York, 2017.

Zumkeller, Adolar. “Manuskripte von Werken der Autoren des Augustiner-Eremitenordens in mitteleuropäischen Bibliotheken (Fortsetzung),” Augustiniana 12 (1962), pp. 27-92.

Online Resources

Laura Light, Primer 1, Sermons, 2013

https://www.textmanuscripts.com/enlu-assets/catalogues/primer/primer-1-sermons/primer-1-sermons.pdf

“Albertus Carpentarius,” Bibale-IRHT/CNRS

https://bibale.irht.cnrs.fr/42946

Bibliothèque nationale de France, “Nicolaus Asculanus,” BnF Data

https://data.bnf.fr/16070759/nicolaus_asculanus/

“Bibliothèque de Sir Thomas Phillipps († 1872),” Bibale-IRHT/CNRS

https://bibale.irht.cnrs.fr/8500

Briquet Online

https://briquet-online.at/

“Charlottesville, University of Virginia Library, M.L. Colker 10,” Bibale-IRHT/CNRS

https://bibale.irht.cnrs.fr/42944

Deutsche National Bibliothek. “Johannes, de Gammundia,”.Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

https://d-nb.info/gnd/102529752

Gelber, Hester, and John T. Slotemaker. “Robert Holkot,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

Fall 2021 edition, edited by Edward N. Zalta

https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/holkot/

“A Guide to the Papers of Marvin L. Colker,” Special Collections, University of Virginia, 2011

https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=uva-sc/viu04072.xml

Holcot, Robert. Commentarius in Librum Sapientiæ, lectio 119, Scholastic Commentaries and Texts Archive

http://scta.info/resource/rhwis-l119

ISTC: International Short-Title Catalogue

https://data.cerl.org/istc/_search/

Paratus. Sermones ‘Parati’ de tempore et de sanctis, Cologne: Conrad Winters de Homborch, [c.1480], ISTC no. ip00091500, Universitäts- und Stadtbibliothek Köln

https://services.ub.uni-koeln.de/cdm/compoundobject/collection/inkunabeln/id/26532/rec/1

Piccard Online

https://www.piccard-online.de/start.php

Roest, Bert, and Maarten van der Heijden. “Bertholdus de Wiesbaden (Berthold von

Wiesbaden, fl. later fourteenth cent.),” Franciscan Authors, 13th-18th Century: A Catalogue in Progress, 16 Nov 2021

http://users.bart.nl/~roestb/franciscan/franautb.htm#BertholdusdeWiesbaden

Van Ess, Leander. Sammlung und Verzeichniss Handschriftlicher Bücher aus dem VIII. IX. XI. XII. XIV. etc. Jahrhundert … nebst einer Sammlung von alten Holzschnitten und kleinen Gemälden … welche besitzt Leander van Ess, [S.l.], 1823

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3181625.texteImage

TM 1296