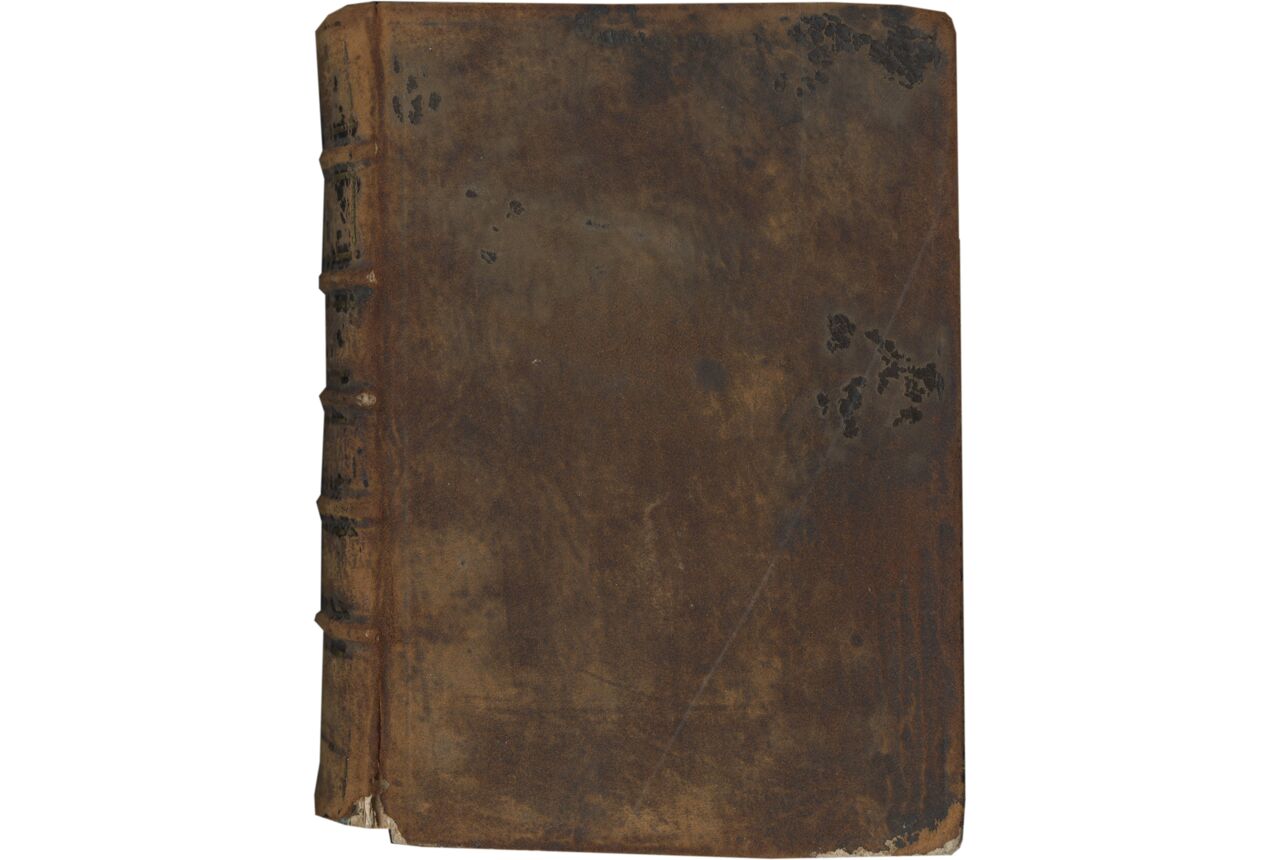

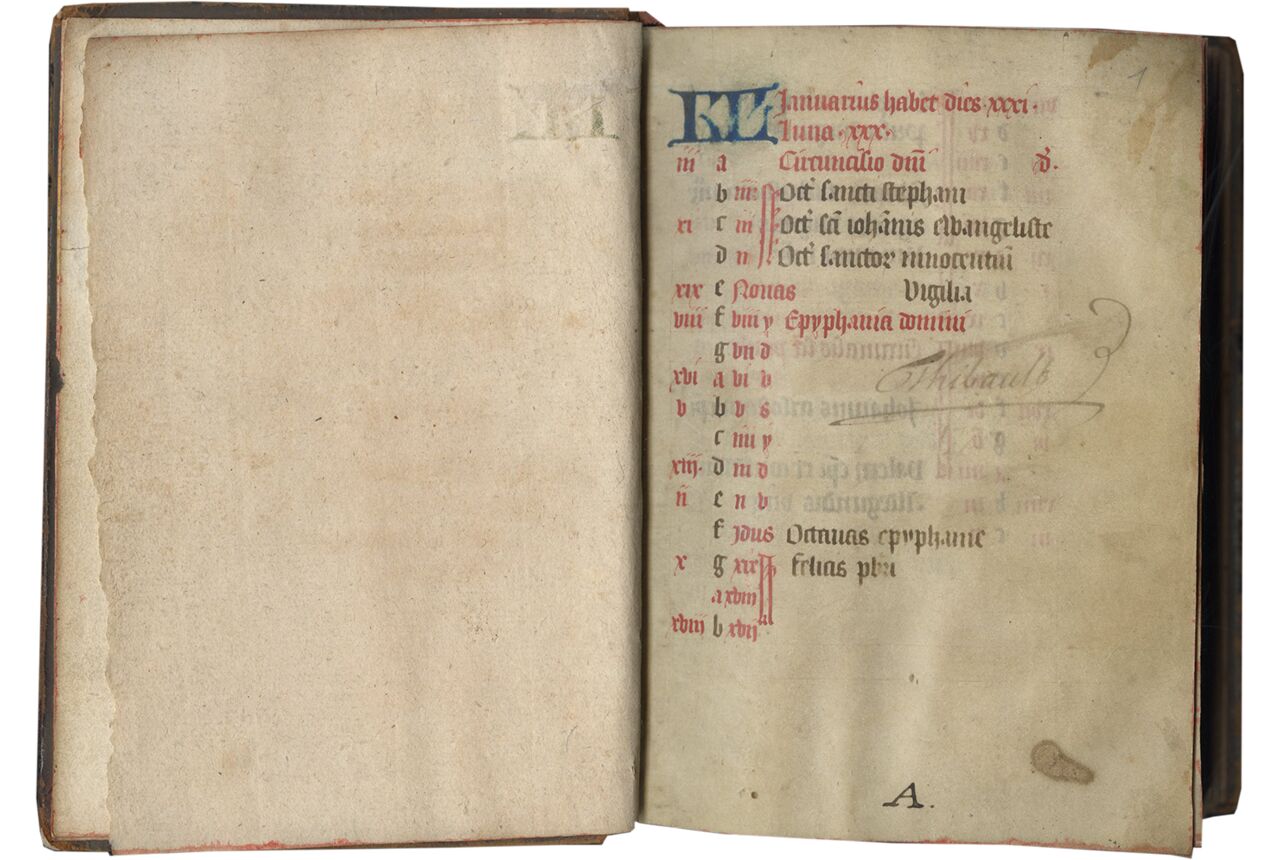

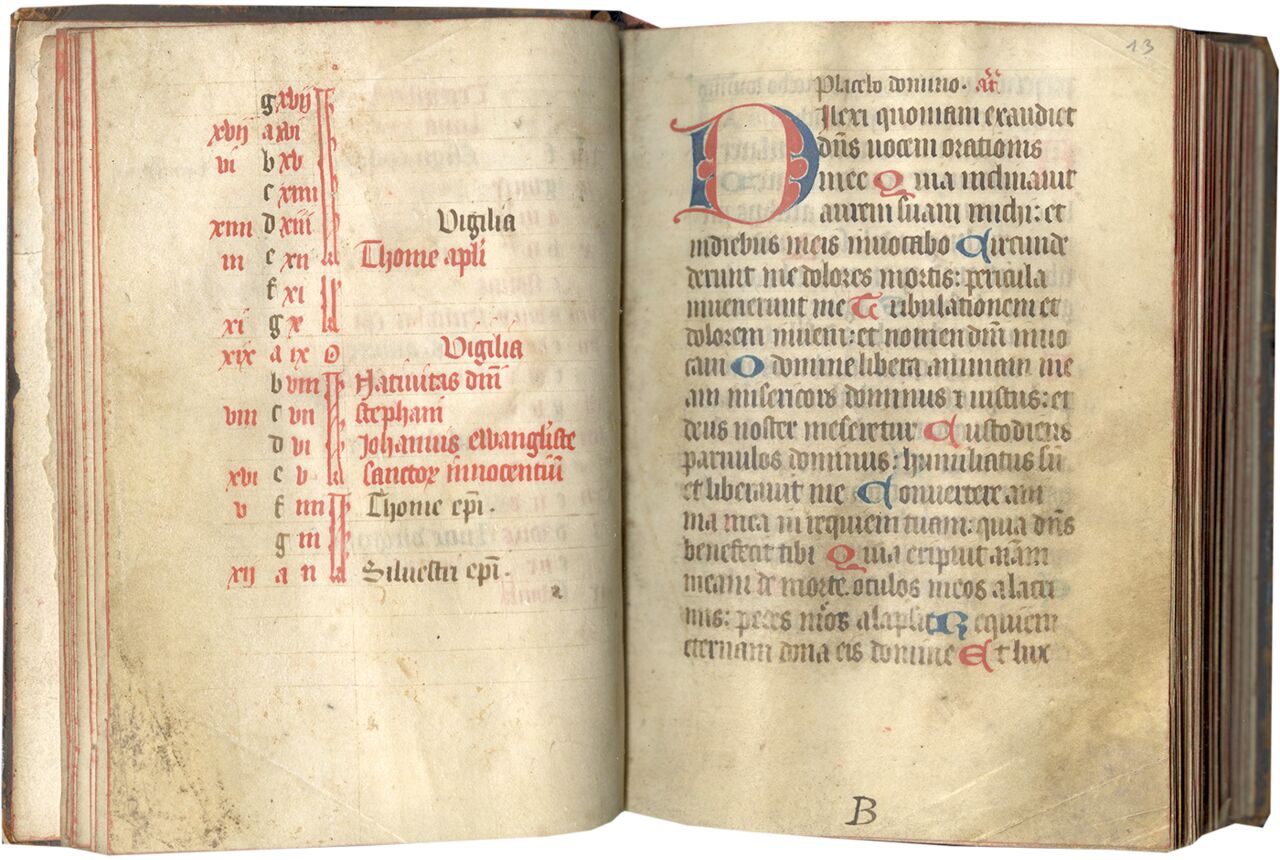

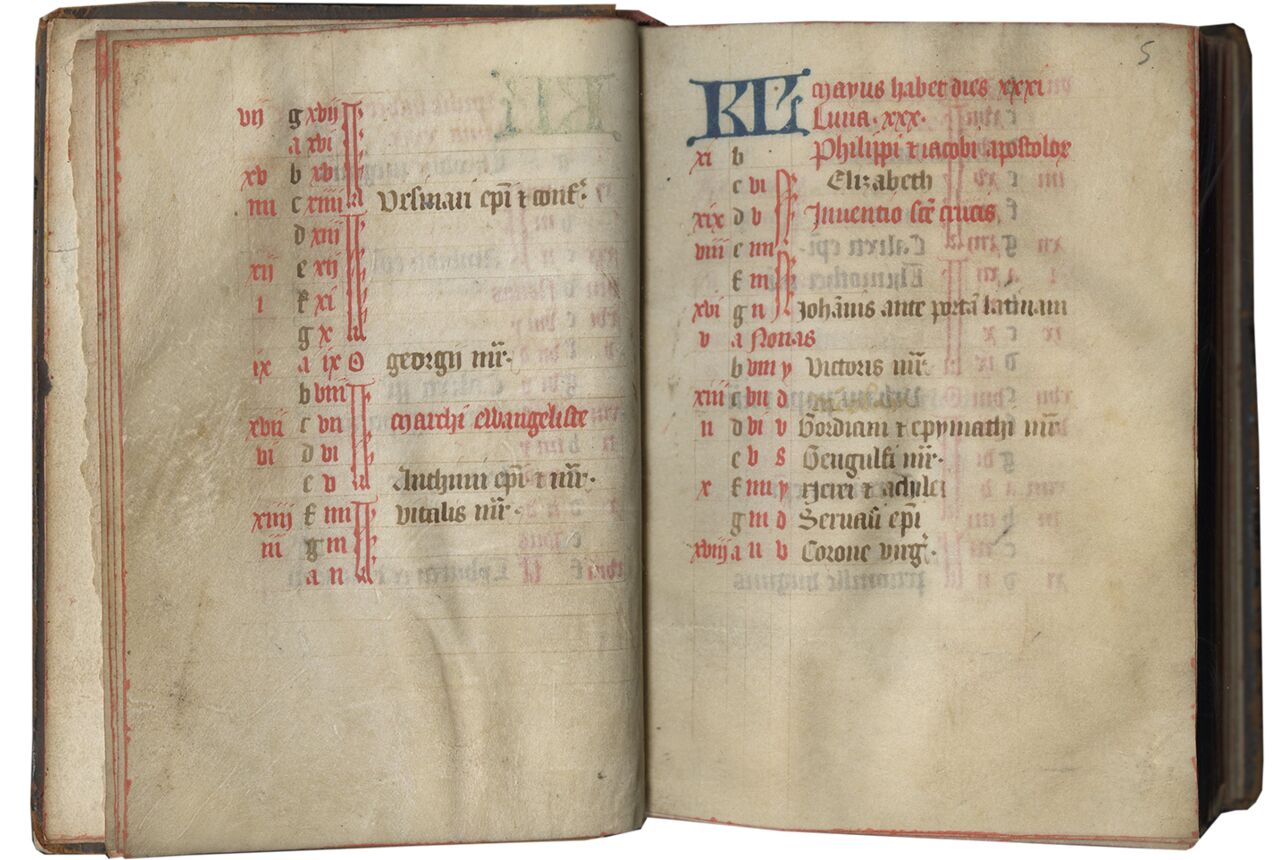

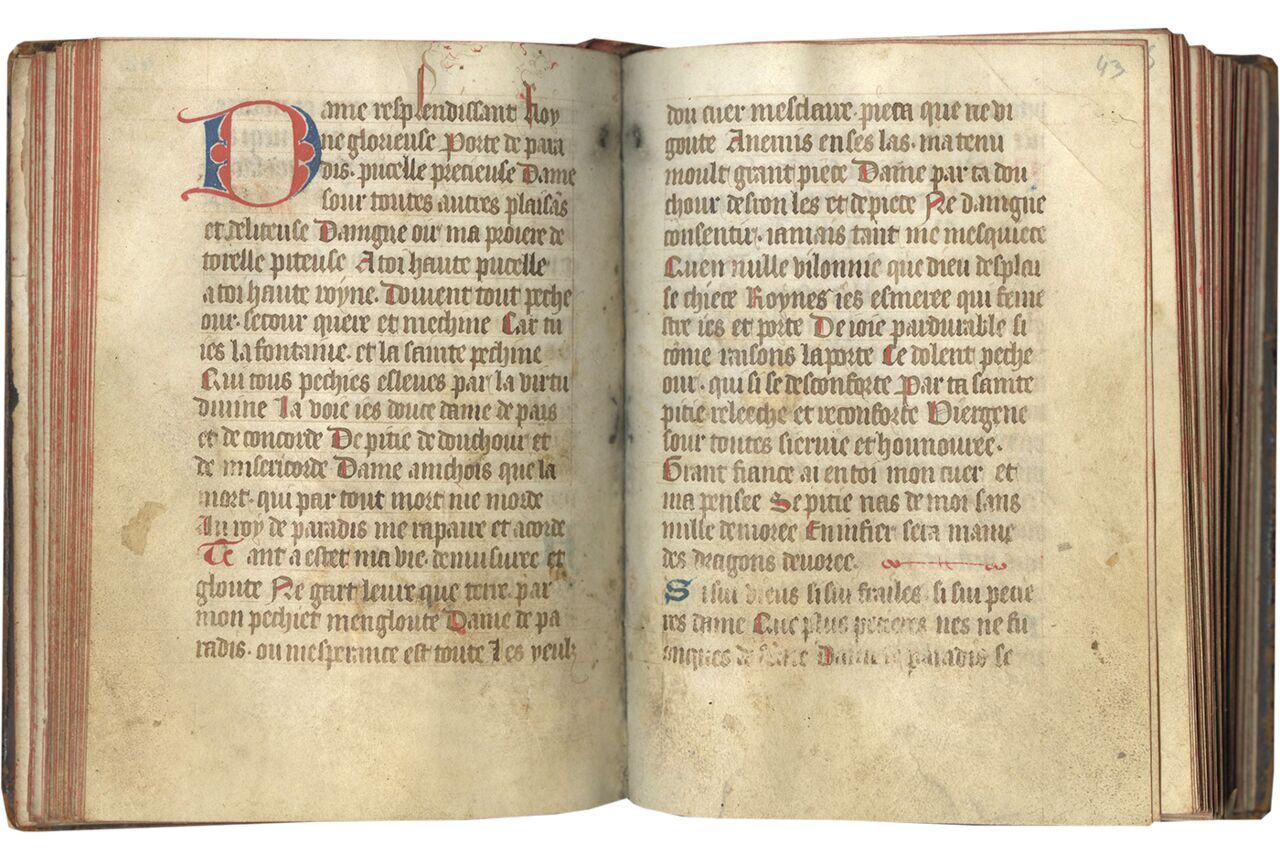

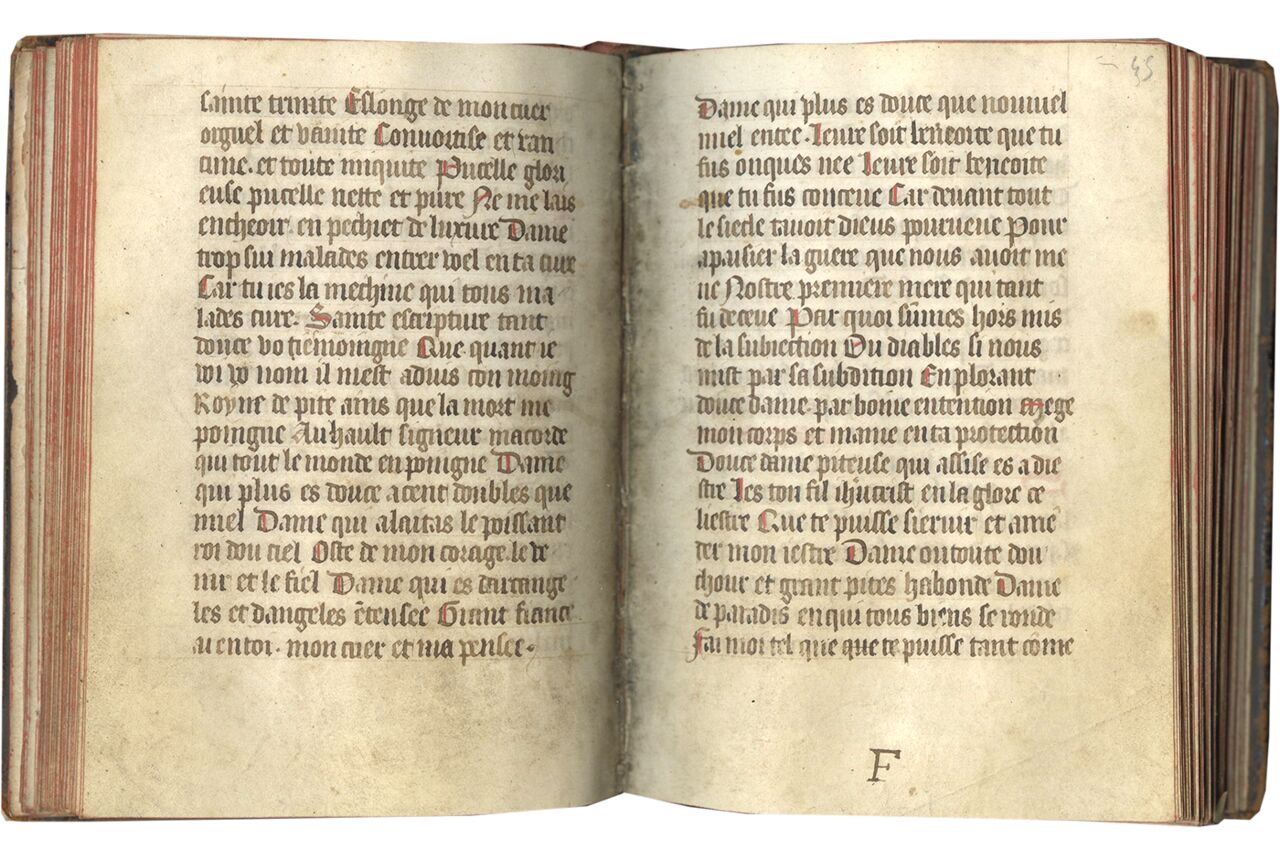

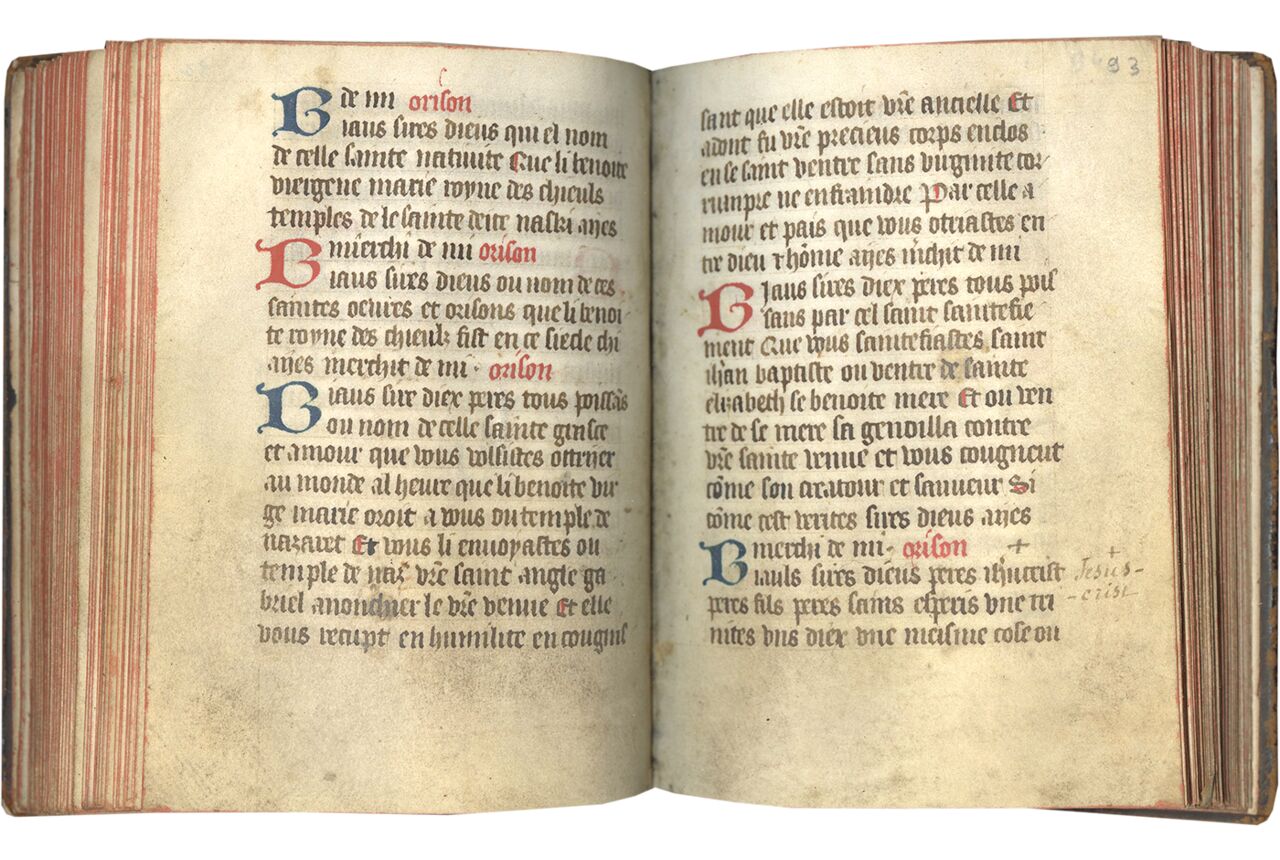

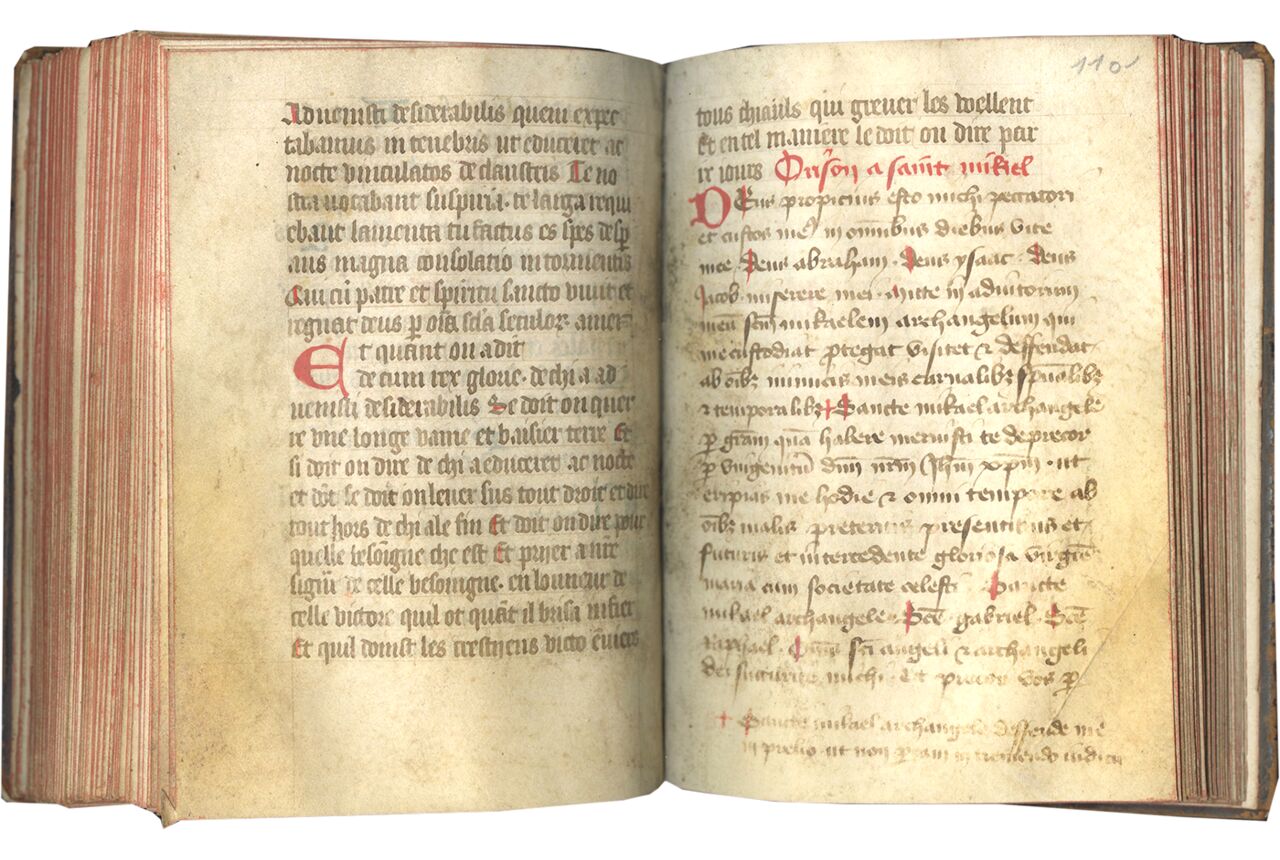

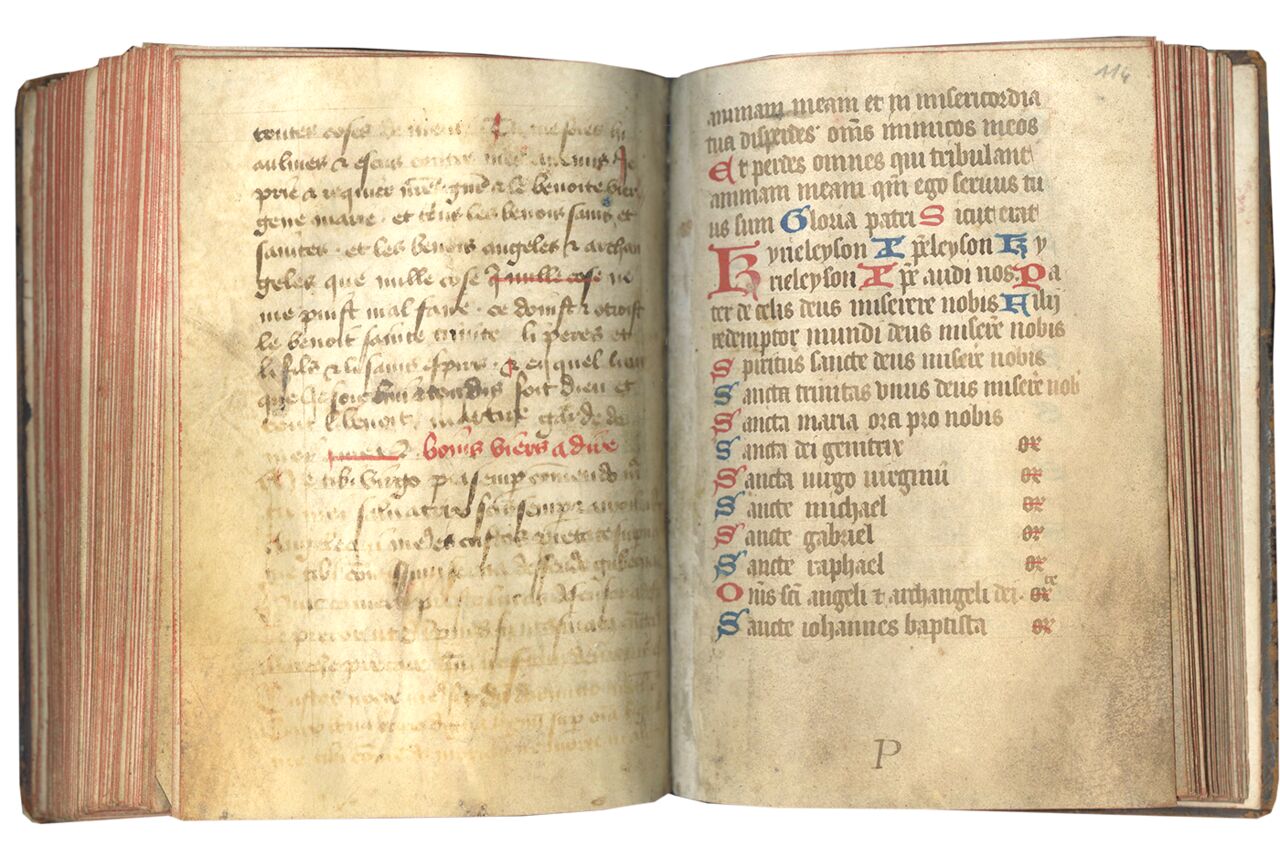

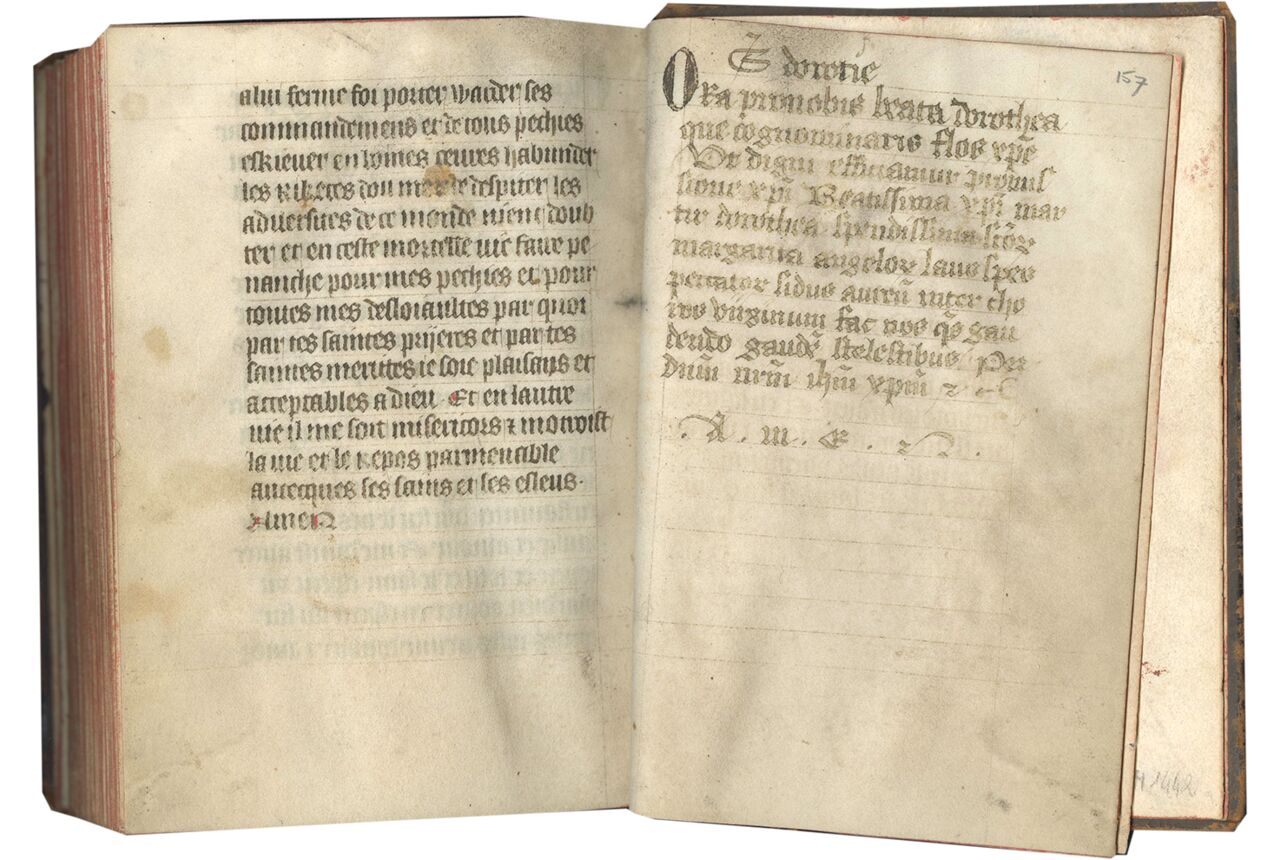

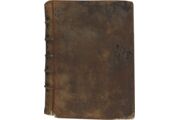

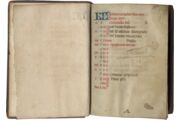

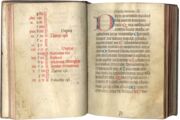

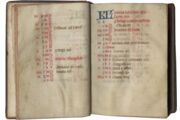

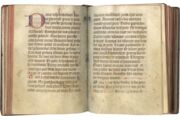

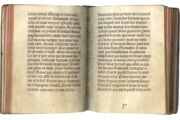

ii (modern paper) + 158 + ii (modern paper) folios on parchment, modern foliation in pencil, 1-158, complete (two leaves removed at the time of making the manuscript, with no loss to content) (collation i12 ii-ix8 x8 [-1, lacking one leaf after f. 76, without loss of text] xi-xiii8 xiv6 xv10 [-10, lacking one leaf after f. 122, without loss of text] xvi8 xvii4 xviii8 xix6 xx10), no catchwords, alphabetical quire signatures added later in the middle of the lower margin in brown ink, A-V, ruled in brown ink (justification 113 x 75 mm.), written in brown ink in a textualis script in single column on 19 lines, rubrics in red, capitals touched in red, 1-2-line initials alternating in red and blue (one red 2-line initial decorated with brown penwork on f. 153v), two 3-line puzzle initials decorated with penwork in red and brown (ff. 138v, 150), two 4-line puzzle initials (ff. 13, 42v), several stains and signs of use, ink partially faded on f. 113v, in overall good condition. Bound in the eighteenth or nineteenth century in brown vellum over pasteboards, five raised bands on the spine, spine gold-tooled in simple fillets and gilt title “MANUSCRIT,” marbled endpapers and pastedowns, pink silk place marker, edges painted red, leather and gold-tooling very worn, otherwise in good condition. Dimensions 152 x 107 mm.

Fascinating Prayerbook certainly made for a woman in one of the female religious communities of Hainaut near Liège. With some texts found in Books of Hours, the manuscript includes many other unusual prayers, written not only in Latin but in vernacular Walloon French with numerous interesting dialectical features. Focusing on women, some of these prayers are composed in an intimate tone and are clearly meant to be read aloud. The volume thus bridges the gap between elite (male) clerical culture and everyday (female) lay devotion while offering rich evidence of language and social history.

Provenance

1. The manuscript was made in the South Netherlands in the region of Hainaut for use in the diocese of Liège or Cambrai, as indicates the overwhelming presence of Hainaut and Liège saints in the calendar and litanies. The inclusion of so many female saints connected to Maubeuge Abbey (Aldegund, Madelberta, Aldetrude, Amalberga) and Mons (Waltrude, Ghislain, Gertrude, Begga) narrows the localization even further. This cluster is very unusual outside Hainaut. Moreover, the orthography reveals the Walloon dialect of the scribe (for a more detailed analysis of the language, see below). The manuscript was made for a woman, as is suggested by the unusually strong emphasis of female saints from Maubeuge, Mons, and the Hainaut region. Furthermore, the prayers in Latin have feminine forms. The inclusion of the translation feast of St. Hubert of Liège in red in the calendar, celebrated only in the Liège/Namur area, and not in France, denotes that the manuscript was made for the diocese of Liège, probably within the geographical triangle that can be traced between Namur, Mons and Maubeuge, in the border area between the dioceses of Liège and Cambrai. The styles of the script and decoration allow dating the manuscript in the third quarter of the fourteenth century.

2. Eighteenth-century (?) ownership inscription “Thibault” in brown ink on f. 1.

Text

ff. 1r-12v, Calendar, including in red the two patron saints of Liège: St. Lambert of Maastricht, diocese of Liège (17 Sept) and St. Hubert of Liège; for the latter, only the secondary commemoration of the translation of his relics on 6 September is in red, which is a feast observed only in some regional or monastic calendars; his relics were translated to the Abbey of Saint-Hubert in Ardennes (diocese of Namur) in the ninth century; his most common feast on 3 November is included in brown ink; notably, St. Lawrence (10 Aug) is also included in red and his octave in brown ink (while universal, he was a major patron of many churches and cathedrals, including a collegiate church of St. Lawrence in Liège, which may explain the emphasis here); in brown ink the local saints include St. Aldegund, founder of Maubeuge Abbey (30 Jan), St. Waltrude (Waldetrudis), the patron saint of Mons (3 Feb), St. Vaast, bishop of Arras (6 Feb, translation 1 Oct) and St. Amand of Maastricht (6 Feb), St Gertrude (17 Mar), St. Gaugericus, bishop of Cambrai (11 Aug; his elevatio 18 Nov), St. Hunegundis (25 Aug, Homblières Abbey, diocese of Noyon, Picardy), St. Willibrord of Utrecht (7 Nov);

ff. 13-42, Office of the Dead, in Latin, unrecorded use, somewhat similar to the use of Soignies in Hainaut (north of Mons) (the responsories in this text correspond the following numbers in Knud Ottosen’s responsory series: 14-72-1 68-83-82 58-93-38, cf. the use of Soignies: 14-72-24 83-93-18 58-79-38);

ff. 42v-57, prayers to the Virgin Mary, first in French, then in Latin, with the final prayers addressing her parents, St. Joachim and St. Anne, as follows: ff. 42v-45v, “Dame resplendissant Royne glorieuse, Porte de paradis, pucelle precieuse...”; ff. 45v-48, “Sainte marie, mere (de) dieu, virge tres piteuse...”; ff. 48-50v, “Je te pri dame saint marie, roine dou ciel, estoile de la mer...”; ff. 50v-51v, a prayer to the Virgin with five stanzas preceded by a long rubric, “Uns honis qui prendons (prendens) fu jadis de religion (un homme qui entrant jadis en religion) li quels estoit bien canonnes (chanoines), et jernaud (Ernault) avoit nom et estoit bien ames de dieu et de le benoite virge marie. Car il les siervoit (servait) nuit et jour moult devotement. Tant que une nuit li beneoite virge marie li apparut en se vision et li monstra en escrit une moult boine (bonne, Picard spelling) orison qui estoit de grant in (de)votion ensi que vous trouveres chi apries escrit. Et li dist Ernaud rechoi ceste orison et le lis devotement cescun (chascun) samedi pour l’amour de mi et le aprens a tant de gens comme tu pues. Et tous chiaus (ceux, Picard form) qui le diront devotement ensi que je t’ai dit, moult grant joie leur avenra car il me veront .v. fois devant leur mort en leur aye et en leur confort,” incipit, “Le premier fie (fois, Picard) qu’il me veront ce fera en le maniere comme je fius quant li angele gabriel m’anoncha...”; ff. 51v-56, the prayer Missus est gabriel, followed by Ave Maria, vera virgo, bothintercepted by “Ave maria” and “Dominus tecum”; f. 56, the collect prayer, “Te precor ergo mitissimam piissimam misericordissimam...”; f. 56v, prayers to St. Joachim and the Virgin, “O Joachim, exulta gaudio jam veteri carens opprobrio anna concepit filiam...” and “Clementissime deus qui per beati Joachim gloriosam progeniem tuam de mundi...”; ff. 56v-57, prayers to St. Anne and the Virgin, “In annam de qua nata nobis est pia virgo maria...” and “Deus qui de beate anne tantam gratiam donare dignatus es...”;

ff. 57v-65v, Fifteen Joys of the Virgin Mary in French, “Belle douce dame sainte marie, Je vous dirai ave maria en le ramembran ce de celle grant joie que vous evistes quant li angeles gabriel vous salua et dist ave maria...”;

ff. 65v-68, two prayers in Latin to Christ and God the Father, f. 65v, “Precor te domine ihesu christe, pro me famula tua ut indulgentiam michi tribuas omnium peccatorum...”; ff. 65v-68, “Dominator domine deus omnipotens qui es trinitas sancta pater in filio et filius in patre cum spiritu sancto ... libera domine animam meam, conserva me in tua voluntate et da michi facere voluntatem tuam quia deus meus es tu. Cui vivis et regnas deus per omnia secula seculorum amen”;

ff. 68v-71, four prayers in French to the Virgin Mary, f. 68v, “Je vous salue tres sainte, tres debonaire, tres misericors, tres douce ma dame, ma mere, mon amie, virgene marie...”; ff. 68-69v, “Je vous salue sainte mere ihesuchrist, Je vous salue virgene sans tache...”; ff. 69v-70, “O vous virgene tres sainte, doit on prijeres offrir sur l’auteil del air, Car chou qui de li naist suffians par vous...”; ff. 70-71, “Tres deboinaire dame faites moi ceste misericorde que al heure de le mort quant ma langue sera pries morte et ne pora parler pour vous...”;

ff. 71-72, a prayer in French to the Holy Cross, “Deleis le crois ihesuchrist seoit se mere et son fil(s), qui a tous vie donnoit, veoit que le siene vie a dieu commandoit...”;

ff. 72-80, five prayers in French and three prayers in Latin to the Virgin Mary, ff. 72-74, “Je te requier dame sainte marie, mere de dieu, plaine de pitie, fille dou soverain roi. Mere glorieuse, mere des orphenius...”; ff. 74-77, a prayer of St. Augustin to the Virgin Mary, rubric, “Monsigneur saint augustin fist ceste devote orison a nostre dame qui chi s’ensieuwent,” incipit, “O vous virgene des virgenes, tres pieuse en l’autel de mon cuer fai sacrefice d’orison...”; f. 77r-v, “Ha tres douce dame de glore, royne de leeche, fontaine de tous biens...”; ff. 77v-78, “O maria piissima, stella maris clarissima, Mater misericordie et aula pudicitie...”; f. 78, “Gaude dei genitrix, virgo in maculata (scribal error; immaculata)...”; f. 78r-v, long rubric in Old Picard dialect, “Uns clers qui salvoit le benoite virge marie devotement cascuns jours de ceste orison qui chi s’ensieut, mais devant se mort il se despera adont li benoite virgene marie sa priant a lui et li dist resiowillis (resjoillis?, modern French réjouissez) vous je vous aporte misericorde” (... and he said, “Rejoice! I bring you mercy”), incipit, “Ave mater misericordie medicina nostre miserie...”; f. 78v, “Flos florum, fons ortorum, regina polorum...”; ff. 78v-80, “Sainte virgene marie je vous prie par celle dolour qui trespassa vostre ame quant vous veistes vostre chier fil(s) souffrir mort et passion en l’auteil de le crois...”;

f. 80r-v, a prayer in French to the Virgin, Christ and all saints to be said 150 times kneeling before a painting representing the Virgin Mary, rubric, “Cils ou celle qui dira ceste orison cent et cinquante fois en genous devant nostre dame elle li acomplira ses desirs mais qui soien a s’en salut,” incipit, “Benoite soit li heure que dieus ihesucrist est nes, Celle viergene marie, En le quelle il est neis soit benoite li heure... et le viertut de tous ains Et de toutes saintes...”;

ff. 80v-89, suffrages in French to the Holy Trinity, the Holy Cross, the Holy Spirit, the Virgin Mary, angels, St. John the Baptist, St. Peter and St. Paul, St. Andrew, St. John the Evangelist (“ewangeliste”), St. James (“sains jaques” and “s. jaquame vostre apostre warmie”), all apostles, St. Peter the Martyr, St. Stephen, St. Lawrence (“lorens” and “leurent”), St. Vincent, St. Lambert, St. Denis (“donis”), all martyrs, St. Dominic (“dominike”), St. Augustin, St. Martin, St. Nicholas, St. Francis (“franchois”), St. Leonard, St. Remy, all confessors, St. Mary Magdalene, St. Elizabeth, St. Agnes, St. Catherine, St. Cecile, St. Margaret, the 11,000 Virgins, and all saints;

ff. 89-105v, two prayers in French to God the Father introduced with “O troies tous poissans diex...” and then a long prayer with each stanza beginning “Biaus sire diex peres...” or “Sires diex peres ihesucrist...”;

ff. 105v-110, two prayers, a psalm and a hymn in Latin to God the Father, “Dominator domine deus omnipotens Dominator domine deus omnipotens, qui es trinitas una pater in filio, et filius in patre, cum Spiritu sancto, qui es semper in omnibus... (prayer of Gregory the Great)”; “Omnipotens mittissime deus per sanctissimum cor tuum...” preceded by the rubric “Ceste orison doit on dire .ix. jours pour toutes tribulations, en l’honneur de celle saint(e) victore que nostres sires eut quant ils brisa les portes d’infier”; psalm 24, “Domini est terra...,” followed by the antiphon “Cum rex gloriae Christus infernum debellaturus intraret”; the text completing here on ff. 109v-110 with the following instructions in French, written in brown ink of the main text: “Et quant on a dit de cum rex glorie, de chi a advenisti desiberabilis Se doit on querre une longe vaine et baisier terre Et si doit on dire de chi a educeret ac nocte et dont se doit on lever sus tout droit et dire tout hors de chi ale fin Et doit on dire pour quelle besoigne che est Et prijer a nostre signeur de celle besoingne, en l’onneur de celle victore qu’il ot quant il brisa infier Et qu’il doinst les crestijens victo enviers tous chiaiils qui grever les voellent Et en tel maniere le doit on dire par ix jours”;

ff. 110-113v, originally blank, seven prayers added in a contemporary cursive hand, the first two prayers in Latin and the last five in French, to St. Michael, Christ and the Virgin, beginning with the rubric “Oraison a saint mikiel,” incipit, “Deus propicius esto michi peccatori...”;

ff. 114-120, Litanies, including St. Aurelius of Carthage, a friend of St. Augustine, St. Lambert of Maastricht, patron saint of Liège (with St. Hubert of Liège), St. Foillan (Feuilllen de Fosses), founder of the monastery at Fosses-la-Ville in the province of Namur, St. Eugenius of Carthage, St. Marcel, St. Blaise, St. Albert, St. Venantius Fortunatus, close friend of St. Radegund (also included), St. Augustine, St. Hilary of Poitiers, St. Vaast of Arras, St. Amand of Maastricht, St. Gaugericus, bishop of Cambrai, St. Aubert (Authberte) of Cambrai (?), St. Ursinus of Bourges, St. Ermine, abbot of Lobbes Abbey in Hainaut (present-day Wallonia, Belgium), St. Ghislain (Gislene) of Mons, monk in Hainaut and the confessor of St. Waltrude (see below), St. Remacle, founder of Stavelot Abbey in the province of Liège, St. Hubert, patron saint of Liège, St. Maximine, St. Etto (Hitto), bishop in Feschaux in the province of Namur, St. Aldegund, founder of Maubeuge Abbey in the county of Hainaut (now northern France), St. Waltrude (Waldetrudis), the sister of St. Aldegunde and the patron saint of Mons and of Herentals (now Belgium), St. Gertrude the Great, St. Aldegund mentioned the second time, St. Madelberta of Maubeuge, who succeeded her aunt St. Aldegund and her sister St. Aldetrude, as abbess of Maubeuge, St. Forminia, virgin martyr, St. Begga, founder of the Andenne Abbey in the province of Namur, St. Brigid of Sweden, St. Amalberga of Maubeuge, St. Nathalia, St. Ragenfredis (Renfroie) of Denain, daughter of St. Adalbert, founder of the Denain Abbey in the count of Hainaut, St. Hunegundis of the Homblières Abbey (diocese of Noyon), St. Movegundis, sixth-century holy woman connected to the shrine of St. Martin of Tours, St. Radegund, and St. Aldetrude, the niece of St. Aldegonde (Aldegund) who became the second abbess of Maubeuge after her aunt; followed by prayers;

ff. 120-138v, prayers and hymns in French for different parts of the Mass and other situations, with instructions in rubrics, including a prayer to call the Holy Spirit, ff. 122v-123, rubric, “Chou qui chi apries est doit on dire pour apeller le .s. esperit,” incipit, “Venes sain espirs et envoyes del ciel le ray de vostre lumiere...”;

ff. 138v-149, the selection of parts of psalms known as the Psalter of St. Jerome; f. 149v, blank;

ff. 150-156v, a long prayer to Christ in French, “Sires ihesucris fils de dieu le vif souverain priestre...”;

f. 157, originally blank, a prayer added in the fifteenth or the sixteenth century to St. Dorothy, “Ora pro nobis beata dorothea que cognominaris...”; ff. 157v-158v, blank.

This prayerbook was clearly made for a woman, as is indicated by the extensive use of vernacular language, the feminine forms in the Latin prayers, and the selection of saints connected to female religious houses. She may have been a nun or a lay noblewoman tied to the regional devotions. The double mention of St. Aldegund, the founder of the Maubeuge Abbey, in the litanies shows the importance of this abbey and its “holy family” of women for the original owner. The litanies also include her relatives, St. Madelbertha, St. Aldetrude and St. Amalberga, who formed a dynasty of holy abbesses at Maubeuge Abbey. Their cult was very strong in Hainaut, especially among women connected to monastic houses. The seventh to the ninth centuries saw a wave of aristocratic women founding abbeys in this region (Maubeuge, Nivelles, Andenne, Denain), and saints like St. Waltrude (patron of Mons), St. Gertrude of Nivelles, and St. Begga of Andenne created a network of female sanctity in the area. For later medieval women, especially noble women, these saints served as models of piety, chastity, and charitable authority.

The suffrages on ff. 80v-89 include a prayer to St. Lambert, showing a strong Liège connection, matching the litanies and calendar, while the prayer to St. Denis, Paris patron, reflects a broader French devotional culture. The prayers to saints Dominic, Francis and Augustine suggest exposure to mendicant spirituality, common among noblewomen in the fourteenth and fifteenth century, who often supported mendicant houses. The prayers to female saints (Mary Magdalene, Elizabeth, Agnes, Catherine, Margaret, Cecile and the 11,000 Virgins) show the expected emphasis on exemplary chastity and piety. Especially interesting is the tone of the prayers, addressed in a familiar way with phonetic vernacular spellings, intended to be read aloud in private prayer; see, for instance, the affectionate, almost spoken tone in a prayer describing “s. jaquame vostre apostre warmie” (Saint James, your apostle and protector; “warmie” being a Walloon spelling of garant, guard, armé, warmie; f. 83, line 16).

Throughout the Middle Ages, French was a native language in the southern areas of the Low Countries: Artois, Cambrai, Hainaut, Liège, Limburg, Luxemburg and Namur (for more on the subject, see Schoenaers and van de Haar 2021, especially p. 4 onwards). The phonetic spellings in our manuscript reflect French pronunciation consistent with the localization of the manuscript in Hainaut/Liège and surrounding Walloon-speaking areas. Examples include the variants “leurent” for St. Lawrence (Latin Laurentius, Old French Lorens) and “donis” for St. Denis, showing diphthong and vowel shifts typical of the Walloon and Picard dialects (f. 84 line 18 and f. 84v line 17). The form “le witisine” for huitième (f. 32, “eigth”) shows the initial “h” to “w” shift and the suffix -isine, both reflecting Walloon phonetics, the former still found in modern Walloon. Further examples of Walloon scribal practice found in our manuscript are provided by the forms “viers” for vers (f. 148, “verses”), “chi” for ci and the phonetic spelling “s’ensieuwent” for s’ensuivent in the rubric on ff. 74-75: “Monsigneur saint augustin fist ceste devote orison a nostre dame qui chi s’ensieuwent.” The scribe wrote in Walloon vernacular French, and more specifically the Wallo-Picard dialect spoken in the western region of Wallonia, not Parisian or central French, making our manuscript especially interesting for the study of language.

In the Middle Ages, this manuscript would have enabled a relatively wealthy woman to engage with devotion personally. Today, the book contributes to our understanding how Prayerbooks helped shape vernacular literary traditions, and the calendar, litanies, and prayers including commemorations to numerous local saints serve as historical records, providing insight into regional religious practices. In short, this manuscript is important because it bridges the gap between elite clerical culture and everyday lay devotion while offering rich evidence of language and social history.

Literature

Boone, M. and W. Prevenier, Belgium and the Low Countries: Social and Economic History in the Middle Ages, Cambridge, 1990

Harper, J. The Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy from the Tenth to the Eighteenth Century: A Historical Introduction and Guide for Students and Musicians, Oxford, 1991.

Legaré, A.-M. Livres d’Heures manuscrits conservés dans les bibliothèques publiques de Belgique, Turnhout, 1999.

Meyer, P. Recueil d’anciens textes bas-latins, provençaux et français, Paris, 1874.

Morey, James. Jerome's Abbreviated Psalter: The Middle English and Latin Versions,York, 2019.

Reinburg, V. French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c. 1400-1600, Cambridge, 2012.

Schoenaers, D. and A. van de Haar, “Een bouc in walsche, a Book Written in French: Francophone Literature in the Low Countries (1200-1600),” Queeste 28:1 (2021), pp. 1-29. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5117/QUE2021.1.001.SCHO

Vanderkindere, L. La formation territoriale des principautés belges au Moyen Âge, Brussels, 1902.

Van Dijk, S. Sources of the Modern Roman Liturgy: The Ordinals of Haymo of Faversham and Related Documents (1243-1307), 2 vols, Leiden, 1963.

Zufferey, F. Manuel de philologie romane: langue, littérature, civilisation, Bern, 2001.

Online Resources

Walloon orthography (Wikipedia):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walloon_orthography

Walloon language (Wikipedia):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walloon_language

TM 1442