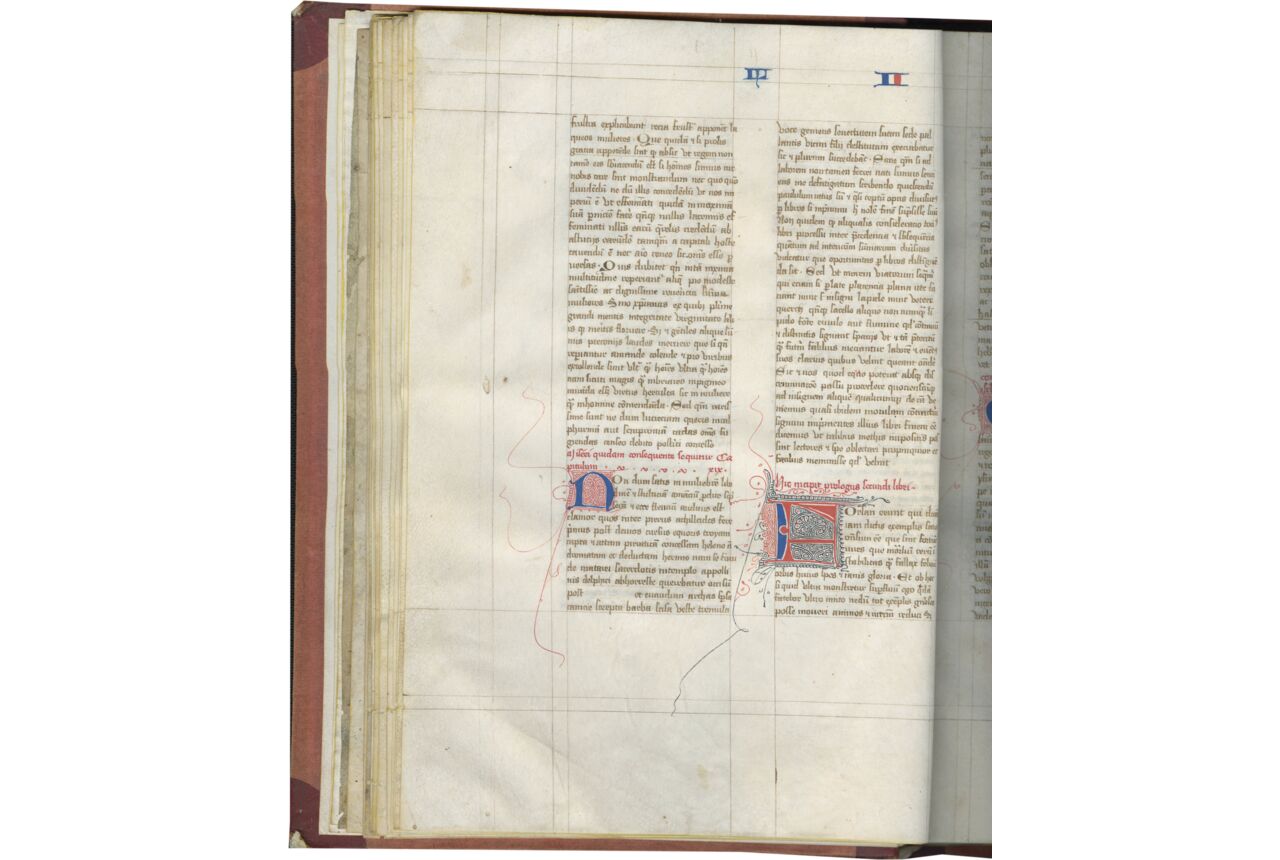

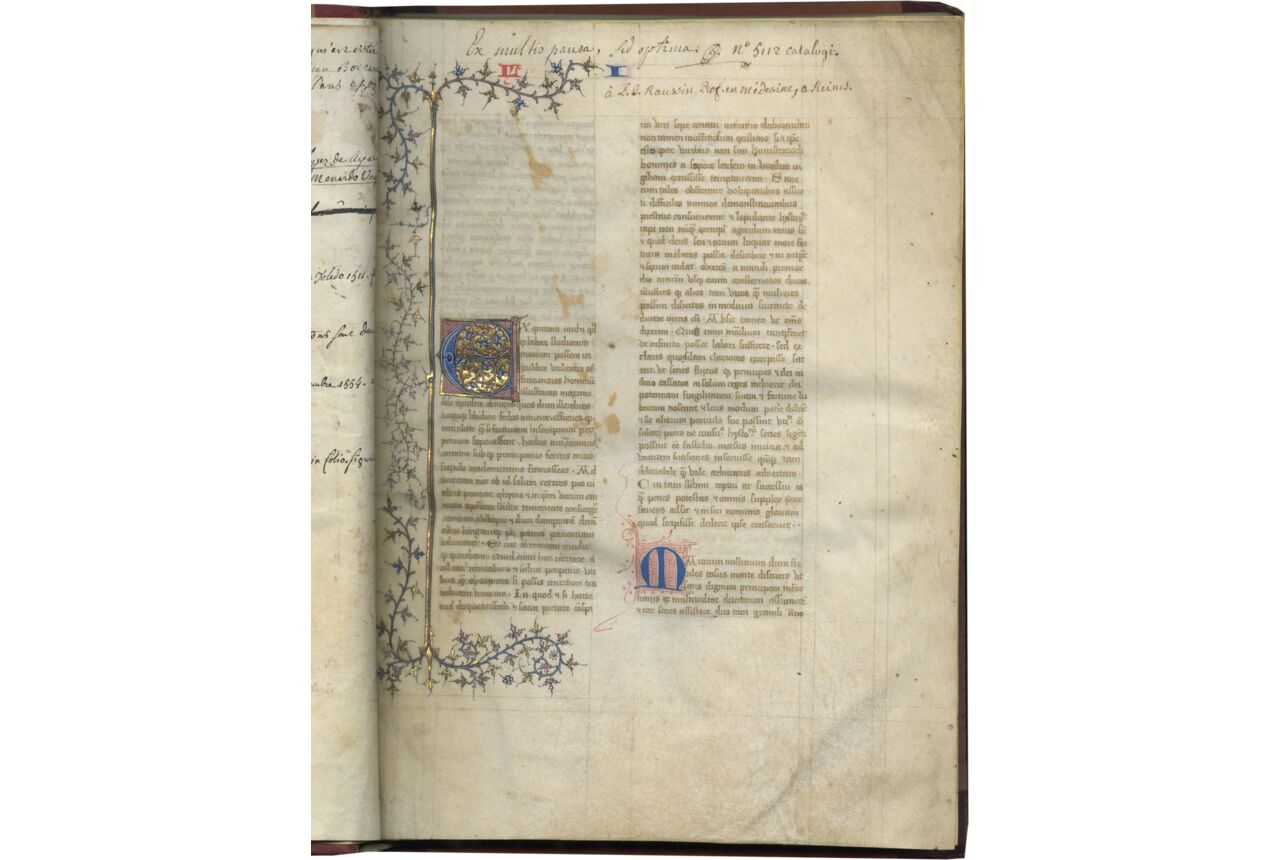

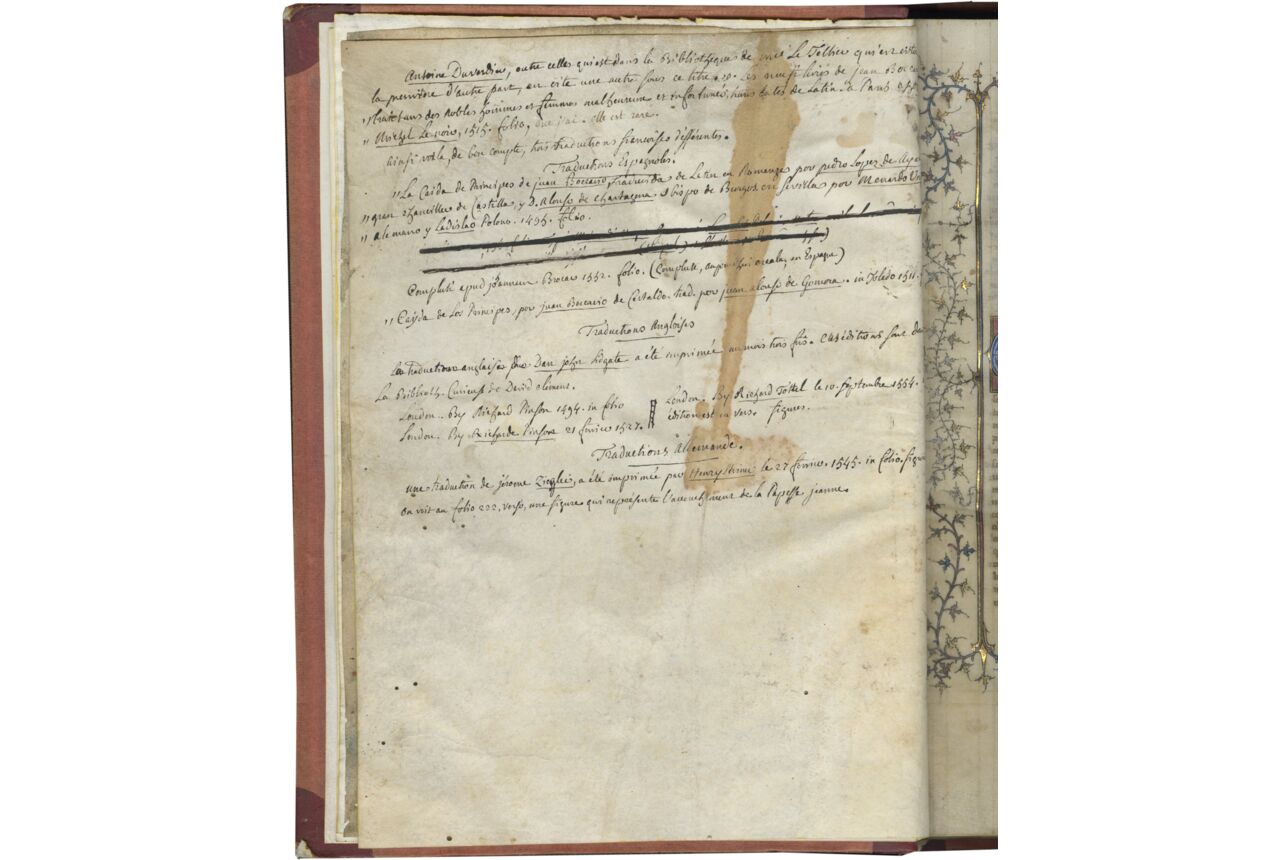

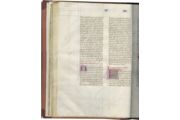

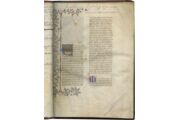

i (original parchment) + 113 + ii (original parchment) on parchment, complete (collation i-xiv8), catchwords throughout, faintly ruled in light brown ink, (justification 200 x 150 mm.), written in a small, square gothic bookhand on 39 lines in two columns, rubrics in red, some capitals touched in red, running titles in alternating red and blue Roman numerals, numerous 2- and 3-line initials in red and blue with contrasting penwork, eight large decorated initials in variegated red and blue with penwork in both colors, ONE LARGE ILLUMINATED INITIAL AND DECORATED IVY LEAF BORDER ON THREE SIDES of f. 1, blank space left for a miniature; some worming at ends, a few minor stains, overall in good condition. Bound in nineteenth-century half red morocco and orange boards, title gilt, yellow edges, boxed. Dimensions 332 x 244 mm.

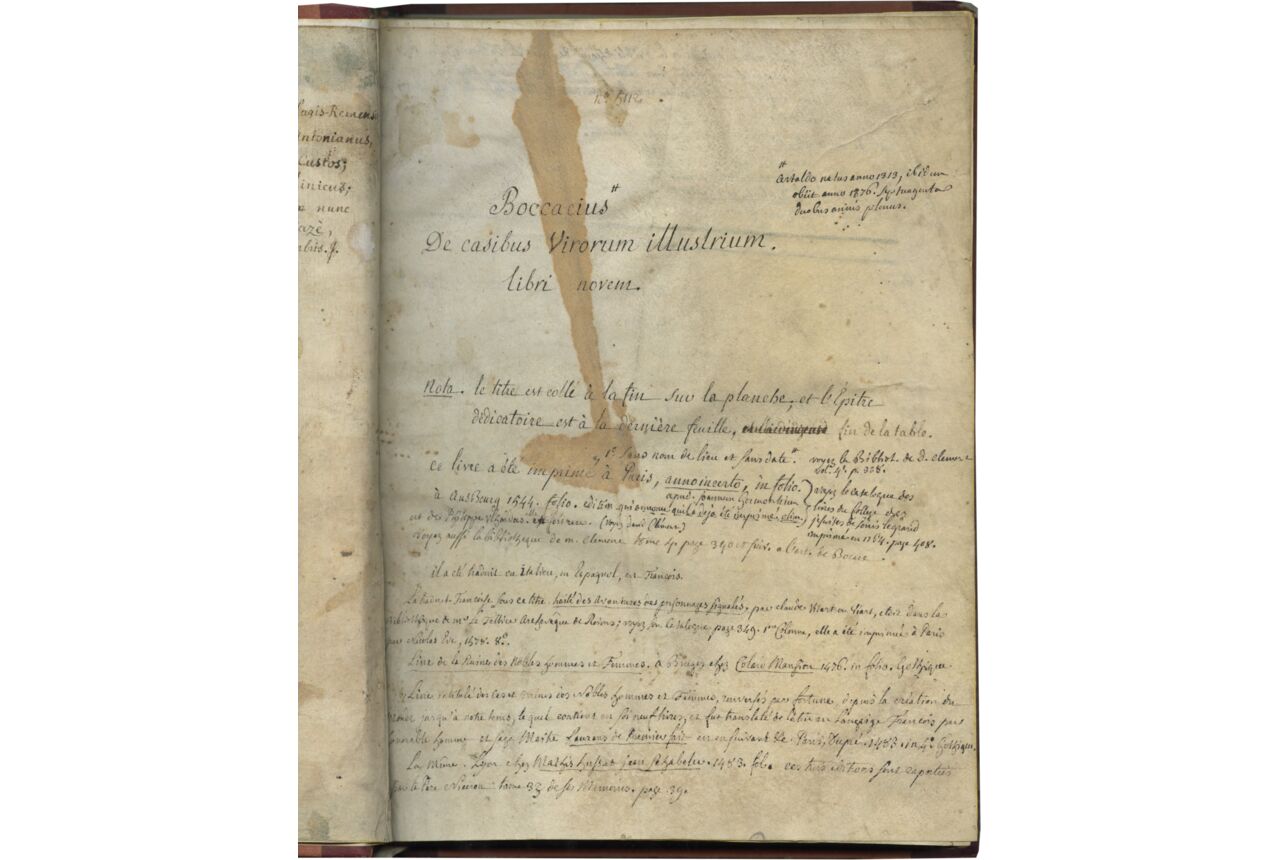

A handsome, beautifully written copy of the first edition of Boccaccio’s moralizing work, giving an account of more than ninety famous men and women, whose downfall he attributes chiefly to the vagaries of Fortune. Unpublished, the manuscript was surely written in Paris (where it was signed by the scribe, once with his name and again with a charming jingle) and is stylistically related to manuscripts produced in the close circle of King Charles VI’s royal court that enthusiastically embraced Italian humanism. Copies are rare in North America; only one was recorded by the editors. The distinguished provenance enhances the volume’s special interest.

Provenance

1. Written by a scribe named Johannes, who conceals his name within the colophon on f. 110v: “Si ‘io’ ponatur et ‘han’ sibi associatur / Et ‘nes’ addatur qui scripsit ita vocatur” (‘io’+’han’+’nes’). This can be read: “if one begins with ‘io’ and ‘han’ is placed alongside, and then ‘nes’ is added to it, [you will arrive] at the name of the scribe.” This form of colophon, in which syllables forming the name are hidden in a longer text, survives in a number of other examples, predominantly from fifteenth-century France (for example, see Bénédictins du Bouveret, 1965-1982, v. 1, nos. 129 and 131 (Albertus), 1690 (Bartholomeus); v. 4, nos. 13656-7 (Michael)). Our scribe may be the Johannes recorded in a near-identical form in the colophon of BnF, MS lat. 5845, a copy of Valerius Maximus datable around the beginning of the fifteenth century (v. 3, no. 8432; see also no. 8480, another “Iohannes” recorded in a longer colophon in a manuscript now in Berlin).

The manuscript must date after 1409 because it includes Laurent de Premierfait’s Latin poem in praise of Boccaccio, which first appeared in Laurent’s second French translation of 1409. The style of its introductory illumination and penwork suggests a date not long after 1409. For general comparisons, see Christine de Pizan, L’Epistre Othéa, Paris BnF, MS fr. 848 (c.1400-1410) and Honoré Bouvet, Apparcion maistre Jehan de Meun, Paris BnF, MS fr. 811 (c. 1410).

2. Remains of medieval title label with author and title in lettre bâtarde pasted inside front board.

3. Louis-Jérome Raussin (1721-1798), professor of anatomy and dean of medicine in Reims and keeper of the university archives there; this with his signature and 18th-century armorial bookplate on front flyleaf, f. i verso, number 5112 in his collection. In 1982, Christopher de Hamel suggested “it is possible that the manuscript is from one of the monasteries of Rheims” (Sotheby’s, December 7, 1982, see below).

4. Reims, Henri Cazé, arch-prior of St-Remy Abbey, gifted to him by Raussin on December 1, 1786 (inscription top margin, f. i verso; and “nunc e cineribus (eheu!) Splendide renascenti dedit”).

5. Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872), Middle Hill, his stamp on the front pastedown; Phillipps has been described as the greatest private manuscript collector of all time, and certainly, his collection of approximately 60,000 manuscripts was the world’s largest–so large in fact that it was still being sold in 1977, more than a century after his death; this his MS 1091, bought from Longman (1771-1842); sold in Phillipps’ sale in Sotheby’s, April 27, 1903, lot 158.

6. William Carr (1863-1925), Ditchingham Hall, Norfolk, British biographer, historian and magistrate for Norfolk; his armorial bookplate on the front pastedown.

7. Sotheby’s, London, December 7, 1982, lot 71.

8. Switzerland, Private Collection.

Text

ff. 1-107v, incipit, “Ex quirenti michi quid ex labore studiorum ... [book nine] …,” Explicit liber boccasii de casibus illustrium virorum;

ff. 108-109, [Alphabetical table of contents], incipit, “Ambitomarus liber v, cap. v…, Et sic es finis tabule et totius libri … Scriptor scripsisset bene melius si potuisset” (the scribe would write much better if he could have a drink);

On this colophon, which appears in manuscripts at least by the thirteenth century, see Lynn Thorndike, “More Copyist’s Final Jingles,” Speculum 12, 2 (1937), pp. 321-328; and “Documents and Records, II, Latin Explicits and Incipits (chiefly from Bodleian Manuscripts),” Bodleian Quarterly Record, 1 (1914), p. 57.

ff. 109v-110v, [Table of chapter headings], incipit, “incipit rubrice … de adam et eve … Pauci flentes et libri 9”;

f. 110v, column 2 [Laurent de Premierfait’s poem in praise of Boccaccio headed in the upper margin by the name “Laurentius primis”(Laurens de Premierfait, the text’s French translator)], incipit “Vatum terra parens … merces equa labori”; [followed by the scribal colophon; see Provenance, above];

On this poem see Patricia M. Gathercole, “A Frenchman in Praise of Boccaccio,” Italica 40, 3 (1963), pp. 225-230. The poem accompanies some manuscripts of the second translation by Laurent de Premierfait, the edition that dates 1409. It also occurs, as noted by Hauvette (1903), in some of the Latin manuscripts of Boccaccio, an observation which caused him to doubt its authorship by Laurent; Gathercole accepts Laurent’s authorship.

ff. 111-11v, [Boccaccio’s (second) Prologue written to Mainardo Cavalcanti (1373)], incipit, “Generoso militi domino mghuardo [sic] de calvalcantibus de Florencia … diu strenue ….”

Boccaccio, De Casibus virorum illustrium, Pier Giorgio Ricci and Vittorio Zaccaria, Milan, 1983, vol. 9 of Tutte le opere, Vittorio Branca, ed.

This codex contains the De casibus virorum illustrium (“On the Fates of Famous Men” or “The Downfall of the Famous”) written by the celebrated early humanist Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375). Considered one of the “three crowns” of Italian humanism, along with Petrarch and Dante, Boccaccio spent most of his life in Florence, with brief sojourns in Naples and Ravenna. He was a friend of Petrarch whom he met first in 1350 and whom he considered his “magister,” and he was a promoter of the works of Dante, some of whose codices he copied. Although he studied law and apprenticed in the bank where his father worked, his chief passion was the writing of literature, both in the Tuscan vernacular and in classical Latin. His best-known work is the Decameron, written between 1349 and 1352 and structured as one hundred tales told by seven men and three women as they shelter in a secluded villa. Other significant works include: the Elegia di Madonna Fiammetta (c. 1343-1344), the Genealogia deorum gentilium libri (c. 1360), De mulieribus claris (c. 1361-c. 1364), and Corbaccio (c. 1365).

De casibus virorum illustrium consists of over ninety biographies of famous men and women organized in nine books of 159 chapters, variously divided (our manuscript contains 170 chapters). The men and women present themselves before Boccaccio and tell their stories. They include biblical figures such Adam and Eve, Nimrod, and Samson in Book One; contemporary persons such as Petrarch in Book Eight and King John the Good of France in Book Nine; many Greek gods and goddesses and Ancient Kings and Queens, such as Cadmus, Arachne, Dido, Julius Caesar, Caligula, Brutus, and Darius, found throughout; and medieval personae, Brunhilda of Austrasia (d. 613), King Arthur of the Bretons, Rosamund Queen of the Lombards (d. 6th century), Desiderius King of the Lombards (d. 786), the legendary Pope Joan, Guy de Lusignan King of Jerusalem (d. 1194).

Boccaccio’s accounts are neither straightforwardly historical nor biographical but rather moralizing, observing the virtues and failings of his famous men and women from the perspective of Fortune, who balances success with reversal and “emerges as this work’s most important character and theme” (Hall, 2018, p. ix). He notes in his introduction that for the reader to find his work more pleasant and useful he will “from time to time add inducements to virtue and dissuasions from vice.” He applauds voluntary poverty, derides tyranny, scorns the enticements of women, and returns again and again to the vagaries of Fortune.

The work exists in two versions, called ‘A’ and ‘B’. The first edition, Version ‘A’, was begun in 1357 or after, because it mentions the imprisonment of John the Good of France and his deportation to London, which occurred in April 1357, and it was completed probably by 1360, just before Boccaccio began De mulieribus claris in the summer of 1361 (see Ricci and Zaccaria, p. xvi). Boccaccio revised Version ‘A’ over a number of years and completed it, as Version ‘B’, only in 1374, when he dedicated it to his friend and patron Mainardo Cavalcanti (d. 1379). Mainardo was from a noble Florentine family, and he went to Naples in 1372 to serve as the marshall of the kingdom of Naples. Boccaccio visited him first in 1362, and then in 1373 Mainardo named Boccaccio as godfather of his children; in return, Boccaccio dedicated the second version of De casibus to his friend.

Ricci and Zaccaria studied the manuscript tradition in preparation for their edition, providing a census of 72 complete manuscripts and 20 partial manuscripts (1983, pp. 875-879, their census corrected the earlier one by Branca, 1958, pp. 84-89). Of the complete examples, 26 are of Version ‘A’, 36 are of Version ‘B’, and 10 are “contaminated.” The “Raussin Boccaccio” was unknown to them, although they cite another Phillipps manuscript (Cod. 3481) among the partial copies. In addition to the editorial and stylistic changes made by Boccaccio in Version ‘B’ (signaled in Hauvette, 1903), the editors note two critical differences between ‘A’ and ‘B’: the presence of the dedicatory letter to Mainardo in ‘B’ and the presence (in ‘B’) or absence (in ‘A’) of a sentence at the end of Book Nine referring to the dedication to Mainardo. They observe, however, that some manuscripts of ‘A’ include the dedication usually found in ‘B’ but lack the concluding sentence. This is the case with our manuscript, a copy of Version ‘A’ that shares this feature (the dedication at the end of the text and the absence of the concluding sentence with two other copies of Version ‘A’: L3, Florence, Laurentiana, Cod. Med. Pal. 228, and W2, Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Vind. 12822). W2 also includes the poem by Laurent de Premierfait, a feature uncommon in Version ‘A’ manuscripts, so it would be worth examining further the relationship between the Raussin copy and the Vienna codex. I have not been able to verify whether L3, which belonged to the Parisian humanist Gontier Col (d. 1418), also includes Laurent’s poem.

From that period onwards throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance De casibus virorum was immensely popular. Laurent de Premierfait’s translations as Des cas des nobles hommes et femmes in 1400 and 1409 for French-speaking nobles exist in 70 manuscripts (the 1409 translation; see especially Hedeman, 2008). It inspired John Lydgate, Geoffrey Chaucer, and William Shakespeare, among others, eclipsing Boccaccio’s now more well-known work, the Decameron. Between 1476 and 1598, it was frequently printed: in France (13), England (6), Germany (1), Spain (3), and Italy (3).

Most copies of both versions are now found in institutional collections. Of the 72 manuscripts recorded by Ricci and Zaccaria, only one copy is in a North American collection, New York, Morgan Library and Museum M.943. The further diffusion of copies is difficult to ascertain, in part because the Schoenberg Database does not always distinguish between the Latin, French, and sometimes even English versions. Certainly, the “Raussin Boccaccio” survives as an impressively large and beautifully written deluxe copy that deserves further study not only in relationship to the complex manuscript tradition, but also in relationship to the French court of King Charles VI and his bibliophile brothers and uncle, the Dukes of Burgundy, Orleans, and Berry, where the manuscript was produced at the height of the court’s enthusiasm for Italian humanism.

Literature

[This manuscript is unpublished (apart from the sale catalogues listed above)].

Bénédictins du Bouveret, Colophons de Manuscrits Occidentaux des Origines Au XVIe Siècle, Fribourg, 1965-1982.

Giovanni Boccaccio, De casibus virorum illustrium, ed. Pier Giorgio Ricci and Vittorio Zaccaria, Milan, 1983, vol. 9 of Tutte le opere, ed. Vittorio Branca, Milan, 1964-1998.

Giovanni Boccaccio, The Downfall of the Famous, New Annotated Edition of The Fates of Illustrious Man, tr. Louis Brewer Hall, New York and Bristol, 2018

Branca, Vittorio, Tradizione delle opere di Giovanni Boccaccio. I. Un primo elenco dei codici e tre studi, Rome 1958, pp. 84-89.

Hauvette, Henri, “Recherches sur le ‘De casibus virorum illustrium de Boccace’, in Entre camarades publié par la Société des anciens élèves de la Faculté des lettres de l'Université de Paris, Paris, 1901, pp. 281-297.

Hedeman, Anne D. Translating the Past: Laurent de Premierfait and Boccaccio’s De casibus, Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008.

Kirkham, Victoria, Michael Sherberg, and Janet Levarie Smarr, ed. Boccaccio: A Critical Guide to the Complete Works, Chicago, 2013.

Marchesi, Simone. “Boccaccio on Fortune (De casibus virorum illustrium),” in Kirkham-Sherberg-Smarr, 2013, pp. 245-54.

Online Resources

http://www.bibliotecaitaliana.it/testo/bibit001350

Edition in Bibliotheca Italiana

https://www.enteboccaccio.it/s/ente-boccaccio/item/10446

Edition and study by Ricci and Zacarria, vol 9 of Branca, Tutti le opere.

TM 1353